"What Kind of a Man Are You?": El Cid & The Invention of a Hero

Few historical heroes boast an afterlife as rich as that of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar. Can we disentangle the history from the mythology?

Hey everyone! We’re back from a little hiatus! Writing a PhD thesis is no joke ya’ll…There’s quite a lot of new faces receiving this newsletter for the first time this month, a fact which I owe largely to the kind recommendations of some of my stupendously talented online history pals! Huge thank you to Beth Reid of History with Beth, Jake Newitt, and Amy from Fair Thee Well. If you are new here and have found me via someone else’s excellent work, please do follow me on Instagram for more history content. As you’ll know if you’re already a follower of mine, given that there’s so many new people joining this community at the moment, I felt that this month was a good time to give you some Substack content that gives you a bit of *me*. This mega two-parter article comes to you fresh out of my day-job and hopefully gives you a window into some of the themes of my ongoing PhD research on heroic literature in medieval and early modern Spain. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for being here - I hope you stick around with me! Strap in.

Picture this. You are Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, a prominent Castilian nobleman and a renowned warrior whom the peasants call ‘El Cid’. Your boss, Sancho (the king of Castile), has ordered that his captured brother, Alfonso (technically the rightful king of León), is to be escorted to a dungeon under guard and imprisoned in a nearby city. Knowing that kings are ordained by God, and having promised this troublesome pair’s father to take care of them both, you decide to pursue Alfonso’s guards through the mountains. There’s thirteen of them and one of you, but God is on your side.

In a fight sequence that lasts approximately three hours, you singlehandedly beat eleven men into the ground, send two fleeing for their lives, and rescue the prince from being bound in shackles. A dazed Alfonso lies in the dirt, bemused by this intervention. Rodrigo is Sancho’s man, but in doing right by God’s law, he has been forced to betray the trust of his rightful liege-lord. In a medieval world where interpersonal loyalties reign supreme, Alfonso is startled that such a man has come to his aid. He asks; dusty, confused, and awestruck; “what kind of a man are you?”

Now, this dramatic bro-down isn’t a figment of my own imagination. I’m describing a scene from the 1961 movie epic, El Cid, where the titular character is played by a Charlton Heston who is poorly aged throughout the film by the odd scar and an extra bit of scraggy beard.1

And Alfonso’s question is actually a great one.

What kind of man was Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the twice-exiled Castilian war hero, better known throughout the world by the nickname ‘El Cid’? Who was he really?

If you’ve seen the film I’ve referenced in these opening lines, El Cid might exist in your mind’s eye as that rugged Charlton Heston, upholding the Christian values of medieval Spain in the face of the bleak totalitarianism of North African invaders. Perhaps, like me, you were first introduced to El Cid through the popular computer game, Age of Empires II, wherein the Cid’s mournful widow, Ximena, regales you with an account of her late husband’s ascent to power, traumatic exile, and his legendary death defending the walls of Valencia. If you’re a keen reader and are familiar with medieval Spanish literature, you might even have read the Cantar de mio Cid (‘The Song of My Cid’). Here, the Cid appears as a wounded father, who, driven by intense regard for the wishes of his king, consents to marry his precious daughters to the scheming Infantes de Carrión, who cruelly mistreat and injure the girls. You might warm to him in his anguish and cheer him on as he seeks the king’s justice for the dishonour done to his only children.

The thing is… none of these Cids bear much resemblance at all to the real Rodrigo Díaz who lived and breathed in eleventh-century Castile.

In this two-part mega article, we’re going to get into unpacking the story of the real Cid, question why its so hard to reliably sketch out the details of his life, and, in Part Two, examine how the ways in which he’s been reinvented over almost 1000 years inform us about the societies that have been attracted to his tale.

And, if you’re interested, I recently had the absolute pleasure of discussing the Cid with Kim and Alice on the Fetch the Smelling Salts podcast where we chatted in depth about Samuel Bronston & Anthony Mann’s epic 1961 adaptation. If you’d like to have a listen to that, you can click here!

Without any further ado, vamos!

Part One: The Man

A Divided Land: The Spain of the Cid

To understand the story of the Cid, we have to first cast our minds back in time to a Spain that is very different from the one that we visit on package holidays today. In reality, what we now call ‘Spain’ didn’t exist in the Cid’s lifetime. The political situation was extraordinarily messy.

Since the year 711 AD, the area of modern Spain and Portugal had been home to a sizeable, wealthy, and powerful Islamic population.2 Manifesting in the first instance as a united caliphate governed from the opulent city of Córdoba, after the 1030s the Muslims of Spain splintered into smaller, independent kingdoms called taifas inhabited by mixed populations of Arabs, Berbers, and other ethnic groups from the Middle East and North Africa.

The north of the peninsula was similarly occupied by fragmented Christian kingdoms who had unbelievably complex relationships with one another. Castile, the kingdom in which the Cid was born, was a scrappy neighbour to the kingdoms of León, Aragón, Navarre, and the Catalan counties of the French borderlands. Despite the fact that the monarchs of these kingdoms were very often close blood relatives, they didn’t often see eye to eye - about anything.

Now, if you’ve got your eleventh-century thinking cap on, you might notice that El Cid’s lifetime roughly corresponds to the build up to the First Crusade.3 You might fairly assume that this violent religious fervour, endemic in northern Europe, would have inspired the knights of Christian Spain, like Rodrigo Díaz, to band closer together and earn their spurs battling Muslims in the south for spiritual rewards, entrenching that contested religious border ever more deeply.

But the binary ideologies of crusade culture didn’t map comfortably onto the reality of political life in eleventh-century Spain.

Unlike the French, Norman, and German knights who set off to ‘reclaim’ the Holy Land for Christendom on the First Crusade, by the eleventh century the Spanish nobility had been living with Muslim neighbours for 300 years already. While for the French knights Muslims existed as geographically distant bogeymen, upon which they could project their cultural anxieties, for the Christian knights of northern Spain, having Muslims on your doorstep, in your towns, and working in your marketplaces was as much an everyday occurrence as Brits bitching about the weather. A crusader’s rigid separation between Christian allies and Muslim enemies just didn’t quite translate to this more fluid environment.4

Having Islam in the neighbourhood had ultimately been pretty lucrative too. North African trade routes under the jurisdiction of the caliphates had allowed luxury goods from the East and gold from sub-Saharan Africa to flow freely into Spain. When the Christian kingdoms felt like bruising each other up a bit over territorial disagreements, the taifa kingdoms of the Islamic south provided a ready source of mercenary soldiers. Christians, likewise, often found themselves fighting on behalf of Muslim kings in mixed armies against foes of all creeds. Each of the Christian kingdoms maintained complex political, economic and military relationships with various Muslim polities, at times charging smaller city states a protection fee called a paria in order to guarantee their security against other belligerent Christian neighbours.

The net result of this complex system of treaties and alliances was that high-ranking Christian noblemen who performed military roles for their kings were extremely likely to have travelled on diplomatic or military campaigns to Islamic courts, more often than not forming personal relationships with their Muslim counterparts while they were at it.

The Spain into which the Cid was born around the year 1043 was a patchwork of warring realms plagued by incessant frontier conflicts and it presented ambitious men of noble stock with countless opportunities for advancement and enrichment. Opportunistic and ever-changing, this network of intercultural relationships is crucial for understanding the trajectory of El Cid’s varied military career. His Spain was deeply unstable, violent, and politically turbulent, but ideological about religious apartheid it was not.

In Search of El Cid: The Sources

“It is peculiarly difficult, in the case of the Cid, to disentangle history from myth.”

- Richard Fletcher, The Quest for El Cid

So, how do we know what we think we know of the Cid? For all that reconstructing the life of a man who was born almost 1000 years ago is never easy, the Cid’s basic movements can be cobbled together via royal charters, official documents, and the few early Christian and Muslim accounts of his deeds that remain. In a period where written biographies of non-royal figures are exceedingly rare, for Rodrigo Díaz we possess some lucky exceptions.

The issue isn’t so much a lack of available evidence, but rather that the evidence we do have lacks detail and reveals tantalisingly little beyond the barest bones of Rodrigo’s bio. Piecing El Cid together from these fragments is like trying to reconstruct someone’s life today out of their birth certificate, a couple of weird social media posts, and a fistful of bank statements. You have something to go on, but it doesn’t necessarily offer meaningful insight into their personality traits and motivations. Conversely, later poetic sources, such as the Cantar de Mio Cid, have personality in abundance but are pretty light on the facts.

Let’s take an example. Most of the available documentation confirms that Rodrigo Díaz was packed off into two periods of exile during his long career, but the extant historical evidence doesn’t give us enough to build a conclusive picture of why that happened. And isn’t that the juiciest bit of the whole drama?5

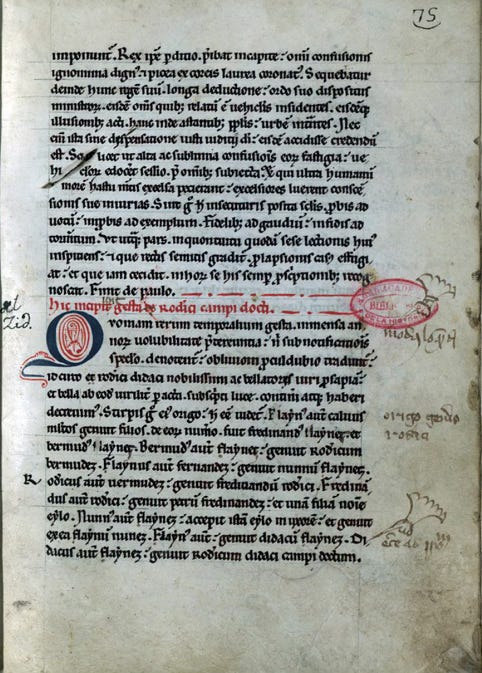

The most authoritative source for the life of the Cid remains the Historia Roderici, a sparse account of the Cid’s exploits written in simple Latin and preserved in a manuscript copied in around the year 1230. It reads a little bit like the headlines on the BBC News at 10. For all it tells us what happened, for the most part it passes little judgement on events, nor attempts to give us rounded portraits of the characters involved. Careful examinations of the copyist’s probable errors suggests that the account might have been originally produced before 1140, within 40 years of the Cid’s death in 1099.6 While it’s important to acknowledge that being written closer to the subject’s lifetime doesn’t necessarily mean the source is more accurate, the unidentified author in this case seems to have been incredibly clued in to the shifting political sands of the Cid’s lifetime. By resisting the urge to brown-nose the Cid too much, the content of the Historia Roderici also suggests that the author was perhaps not on the payroll of the Cid’s immediate relations.7

On the other end of the emotional spectrum, El Cid’s career marauding around at the head of an army occasionally shows up in the writings of his Muslim adversaries. Fragments have survived to us written by two Moorish historians, Ibn ‘Alqama and Ibn Bassam, within a relatively short time of the Cid’s death. Having been at the sharp end of the Cid’s sword, these accounts are devoid of the urge to flatter that warps many later Christian sources and instead offer us an often emotive portrait of a vicious and merciless warlord. The truth, as is often the case, must lie somewhere between these two extremes.

The limitations of this evidence, either lacking in emotional detail or the quite the opposite, are precisely why the Cid’s story is so readily mythologised by later medieval works of Spanish literature like the Cantar. For all that successive generations of storytellers could agree that the Cid was a remarkable man, when you’re left with a superficial portrait and a biography with more holes in it than a slice of Swiss cheese… if you want to tell a good story, you have to fill in some gaps. As minstrels and chroniclers attempted to shape the Cid story into a coherent narrative, each retelling forged Cidian legends that appealed to the particular tastes of their audience. Some of these embellishments, once replicated in a few different versions of the story, ultimately ended up sticking - the simple reason being that the inventions were far more exciting than the nebulous and morally ambiguous truth. If we can gradually peel back layers of hearsay, nonsense and fantasy, it is still possible to uncover the eleventh-century Cid of Old Castile.

The Man from Vivar

Rodrigo Díaz was born around the year 1043 in Vivar, close to the Old Castilian capital of Burgos. In the Cantar de Mio Cid he’s frequently referred to as “that man from Vivar” which, while the poem is the source of a lot of historically questionable content, seems an odd detail to invent out of thin air.8 Unlike in the poem, however, which creates a rags to riches storyline for our hero, we can be fairly certain that Rodrigo was born of good aristocratic stock. Rodrigo's father, Diego, and his grandfather, Laín, served close to the centre of power in the court of King Fernando I of León-Castile, holding castles in the king’s name and distinguishing themselves through military action in Fernando’s many battles against his brother, García, the King of Navarre.9

Given that Rodrigo was able to sign his own name later in life, we can assume that he was given an education of sorts. More important for an eleventh century man than learning how to wield a pen, however, was learning how to wield a sword. As early as his mid-teens Rodrigo was placed in the household of Prince Sancho to serve him as a squire. While learning the ropes of combat amongst other young noblemen, he was probably knighted by his royal master as a teenager.

Military experience came thick and fast for the offspring of noble families in the chaos of the medieval Spanish kingdoms. Rodrigo’s first taste of major battle was likely the Battle of Graus in 1063 where he accompanied the young prince Sancho on a joint expedition with the Muslim King of Zaragoza, al-Muqtadir, to reclaim the town from Sancho’s own uncle, King Ramiro I of Aragón. The first of many times Rodrigo would ride at the head of a mixed Christian and Muslim army, they delivered Sancho a thumping victory, killing poor old uncle Ramiro in the process.

With the death of King Fernando two years later, Rodrigo’s man Sancho, was promoted to the King of Castile, with his brothers, Alfonso and García, receiving the territories of León and Galicia respectively. With his long-time boss now in the top job, the Historia Roderici claims that Rodrigo promptly took up the ceremonial position of the king’s arms-bearer, securing himself some tasty royal privileges in the process. Aside from their ceremonial duties, the king’s arms-bearer was responsible for the command of the king’s personal guard, working closely with him on a day to day basis. A slew of royal charters witnessed by Rodrigo between 1066 and 1071 add significant weight to the claim that Rodrigo had become one of Sancho’s most favoured sidekicks. We can tentatively venture that, being a similar age and having spent much of their adolescence in each other’s company, the two men might well have formed a genuine friendship.

As King Sancho II of Castile started flexing his muscles over the course of the late 1060s and directed military campaigns against the Navarrese and his own brothers, it seems very likely that Rodrigo Díaz, his loyal champion, would have been at the king’s side throughout.

Brother Against Brother

By summer 1072, everything was looking good for young Rodrigo. Sancho’s playground bully routine with his brothers had really paid off. García, was successfully deposed as king of Galicia in 1071 and, after a major scrap at Golpejera, Sancho had also captured Alfonso, seizing the kingdom of León for himself.

But Rodrigo’s so far uncomplicated rise to power as the right-hand of the king suddenly hit a roadblock. On the 7th October, just months after assuming Alfonso’s Leonese crown, Sancho was brutally assassinated outside of the town of Zamora.10 Alfonso, whose situation had been looking pretty dire just months before, swiftly replaced his murdered brother on the throne and swept into power as Alfonso VI, King of Castile and León.

Such a rapid reversal of fortune had the potential to be problematic for Rodrigo. Mere months after clashing swords with his men in battle, Alfonso was now Rodrigo’s boss. After he’d spent years cultivating a pally relationship with the new king’s most dangerous enemy, Rodrigo might well have been anticipating grim repercussions.

Indeed, many of the poets who wrote the story of the Cid in the later Middle Ages saw this moment as a crucial one, claiming that Rodrigo was immediately sent into exile due to Alfonso’s profound mistrust of his brother’s former confidant. Going further, a myth developed that in his grief for his former master, El Cid compelled Alfonso to swear on holy relics that he had played no part in Sancho’s death. Outraged by the Cid’s insolence, Alfonso banished him from the kingdom, forbidding the peasants to aid him in his exile.11

Dramatic, right?

Unfortunately, the Historia Roderici tells us a different, more likely, and much less thrilling story. According to the author:

“after the death of [Rodrigo’s] lord King Sancho, who had maintained and loved him well, King Alfonso received him with honour as his vassal and kept him in his entourage with very respectful affection”.

As delicious and compelling the tales of a righteous man caught between two fratricidal brothers are, in reality the political merry-go-rounds caused by intra-familial violence and royal assassinations were all quite standard procedure at the time.

Though we have evidence that Alfonso did not hold Rodrigo in the same esteem that his brother had done (he loses his job as arms-bearer to a Leonese counterpart, Count García Ordóñez, for example), it would have been foolish of Alfonso to outlaw a talented military commander out of pure pettiness.

Despite being ousted from the inner circle, documentary evidence confirms that in the mid-1070s, Rodrigo makes an advantageous marriage to Ximena, a relation of the king and a daughter of a Count of Oviedo. Ximena’s origins are hazy, but as a high ranking Asturian noblewoman and a relation of Alfonso, it is deeply unlikely that such a match would have been allowed to go ahead if Rodrigo had still been in the royal doghouse. The documents that survive recording the legal settlements of his marriage paint a picture of a man who, though perhaps not the king’s best pal, is accruing a healthy portfolio of lands and castles while carrying out important official duties at court like presiding over legal cases. This all speaks to the fact that having faithfully served Sancho, Rodrigo was charismatic, diplomatic, wealthy, or just plain bloody useful enough to have also convinced Alfonso to keep him close.

Vigilante Shit (Rodrigo’s version)

Here begins Rodrigo’s villain era.

While the ballads might have been off about the exact cause of El Cid’s dramatic exile, it is historical fact that in the 1080s, everything Rodrigo had accomplished in Castile came crashing down around him. The summer of 1081 saw Rodrigo hastily booted out of the Kingdom of Castile-León, his relationship with King Alfonso well and truly soured.

Exile was a common punishment in medieval Spain. Alfonso himself had spent time in exile in the Muslim court of Toledo after having lost his kingdom to Sancho, and many a troublesome knight in exile found himself eagerly employed by the Muslim leaders of the taifas who were always looking for talented mercenaries to support their territorial and political ambitions.

For all that we can probably discount the forced oath of innocence as the cause for this breakdown in relations, what is frustrating is that the exact reason for Rodrigo’s exile remains unclear. That being said, there are clues we can piece together.

A few years before, Rodrigo had been sent south on Alfonso’s behalf to collect tribute from the Taifa of Seville. In vague circumstances, he ended up accompanying Sevillian forces into battle against the neighbouring Taifa of Granada and won a victory for them at the Battle of Cabra.

There was a problem with this, however. Another delegation of Alfonso’s Christian knights had been sent on an identical tribute-collecting embassy to Granada, and those knights had opted to join the opportunistic Abd Allah, King of Granada, on his expedition against the Sevillians, putting factions of Alfonso’s fighting men on opposite sides of this battle for Islamic regional supremacy.

During El Cid’s stunning victory on behalf of Seville, a few very significant Christian knights fighting on the Granadan side were taken into custody and deprived of their goods for three long days while they waited to be ransomed. This list of high-level hostages included Count García Ordóñez, husband to a Navarrese princess, and the man who took Rodrigo’s job as the king’s arms-bearer after the death of Sancho. It’s hard to imagine that Alfonso would have taken this well. It’s also hard to imagine that Rodrigo didn’t get a massive kick out of humiliating his rival at court in such a spectacular way.12

In any case, this episode seems to have put the Cid and the king on rocky terms. Rodrigo was establishing himself as an extremely powerful military commander and as a bit of a loose cannon. Against this backdrop of increasing mistrust, in 1081, the year of the Cid’s exile, it looks like he led an unsanctioned raid into the territory of Alfonso’s Muslim ally, the Kingdom of Toledo.

The Historia Roderici defends this action as honourable redress for previous Toledan raids into the lands of the Cid, and claims that the reason for the exile shortly after was that “many men became jealous and accused him before the king of many false and untrue things”.

Count Ordóñez and co., sick of having a powerful rival at court outwit them on the battlefield, might well have whispered in Alfonso’s ear in order to send him packing, but it's equally likely that the Toledan raid was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Repeated maverick acts of insubordination may have prompted Alfonso to make an example of the Cid, his sudden banishment sending a message to other unruly frontier nobles whose independent responses to personal quarrels threatened the Crown’s foreign policy objectives.

As-Sayyid: El Cid in Exile

Banished from his homeland with his Castilian lands confiscated, the exiled Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar was in desperate need of a new master. Furthermore, his options in terms of suitable candidates were quite limited.

He’d served in a battle that killed the former King of Aragón, so there was no love lost there. And he’d previously defeated and taken hostage Count Berenguer of Barcelona. So, in effect, the Catalans wanted nothing to do with him either. The Taifa of nearby Toledo was prosperous, but it was Alfonso’s close ally, so that one was a no go zone too.

Finally, friendless and running out of choices, Rodrigo arrived at the court of al-Muqtadir of Zaragoza. Way back in 1063 Rodrigo had accompanied the forces of Zaragoza in the aforementioned battle with the Aragonese as a young man. We can theorise that it was contacts that he had maintained at the Zaragozan court from his youth who might have signalled to him that he would be well received there. As it turns out, he was.

Over the course of a five-year period, Rodrigo Díaz served three generations of Zaragozan royalty: al-Muqtadir, his son al-Mu’tamin, and his grandson al-Musta’in. Moreover, the Historia Roderici gives us the impression that the Cid’s personal relationship with the emirs, especially al-Mu’tamin, was quite a cosy one:

“Al’Mu’tamin was very fond of Rodrigo and set him over and exalted him above all his kingdom and land, relying on his counsel in all things”.

Though the Historia might have overstated Rodrigo’s importance, in 1082 it appears that he was placed at the head of an army and charged with organising a defensive strategy for the Zaragozan borderlands - a position of enormous responsibility. Marching against the combined forces of Aragón and Catalunya, as well as the disgruntled relatives of the emir with rival claims to the throne, El Cid delivered victory after victory for his Moorish masters.

It may well have been during this time fighting on behalf of the Zaragozans and pulling off insane victories against all the odds that Rodrigo Díaz first came to be known as ‘as-Sayyid’. This honorific Arabic title was a label bestowed occasionally upon prominent leaders and translates loosely to ‘lord’ or master’. In the fumbled pronunciation of the romance-speaking peoples of Christian Spain, this title was gradually mangled into the nickname, El Cid.13

The dramatic year of 1086 serves as a good example of just how fickle the will of a king and a man with an army could be in this mercenary landscape of political chaos. Early in the year, Rodrigo had led the armies of Zaragoza in defence of the city, forcing back the forces of his former master Alfonso. And yet, in spite of raising swords against his former king, by December that same year, after a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Sagrajas, a bruised Alfonso sent for the Cid and reconciled with him, in recognition of a growing threat looming to the south: the Almoravid Empire.14 Despite years of violent personal animosity, Rodrigo’s success in Zaragoza seemingly forced Alfonso to bring his former commander back into the fold. The deal must have been lucrative. It is highly unlikely that Rodrigo could have been lured away from the luxury of Moorish court life and the riches he had gained conducting cross-border raids without demanding a hefty transfer fee.

Relations deteriorated again as suddenly as they’d been patched up. After three more years of loosely doing Alfonso’s bidding, but simultaneously amassing a private army of his own, in 1089 Rodrigo was called to Alfonso’s aid at the Siege of Aledo. This scrappy little border fortress was garrisoned with a gaggle of Christian knights and found itself under heavy assault from the Almoravids in an isolated position. In a frenzied panic, Alfonso sent word to the Cid, who was collecting tribute in Valencia, and demanded that he bring his army to break the siege.

But the Cid never came.

Whether Rodrigo’s no-show was the result of a genuine miscommunication or a deliberate act of defiance, he was once again ousted from Castile, heading into an undignified exile for a second time.

This time, however, he took his armies and mountains of Moorish gold with him.

The Prince of Valencia

By the time Rodrigo was sent into his second exile, our hero was DONE taking orders. With a vast army of eager followers at his side, attracted to him through the promise of loot and plunder, the Cid turned his back on Alfonso’s authority for the final time and set about carving out a kingdom of his own.

As his armies ravaged the region surrounding the city of Valencia in the 1090s, large payments of tribute from local Moorish warlords were redirected to the Cid, inflaming the tempers of the Count of Barcelona, King Sancho-Ramírez of Aragón, and King Alfonso of León-Castile, who all found their coffers depleted by Rodrigo’s military interferences.

One more than one occasion, this frustration with Alfonso’s wayward former general boiled over into violence. El Cid and his army, ambushed by the Count of Barcelona’s forces, won an unexpected victory in unfavourable mountainous terrain against overwhelmingly superior numbers, taking Count Berenguer of Barcelona hostage for a second time in his career.15 In 1092, the Cid turned his men toward’s Alfonso’s territory, sacking the region of La Rioja and wasting the city of Logroño. It was perhaps not a coincidence that much of the land in these counties belonged to his old nemesis, Count García Ordóñez.

As the Cid amassed soldiers, booty and fortified cities on the agricultural plains of the Spanish Levante, all he had left to do was be patient. Valencia’s political situation was notoriously unstable. Al-Qadir, a disgraced former emir of Toledo, had been installed in Valencia as a puppet ruler by Alfonso, but due to mismanagement and corruption had quickly become deeply unpopular with the locals. When the city inevitably erupted into revolt in 1093, killing al-Qadir in the process, Rodrigo’s time to shine had finally come. Laying heavy siege to the city and using starvation as a weapon against the defenders, the gates of Valencia opened to their new conqueror in June 1094.

The Cid had little time to enjoy his conquest before having to fight to defend it. By October, Almoravid armies had swarmed the plains surrounding the city, intending to retake the lucrative port for themselves. According to the Primera Crónica General, a history of Spain compiled in the thirteenth century by the historians of King Alfonso the Wise, the Cid led a daring surprise attack at dawn, dealing the Almoravids their first heavy defeat.16

Ibn ‘Alqama’s contemporary account from the Muslim perspective gives a little more detail, explaining that the Cid divided his forces into two, sending a large dummy force out of the front gate, while secretly leading a second force from another gate to decimate the Almoravid rearguard. In partnership with the newly crowned King Pedro I of Aragón, the Cid obliterated the Almoravids again in the winter of 1096. Whatever the details of the various skirmishes that took place, it seems that at this crucial point in the growth of Almoravid power on the borders of Christian Spain, Rodrigo Díaz had discovered a formula for beating them when no-one else had been able to.

Having served six kings, Christian and Muslim alike, El Cid finally had secured a kingdom of his own. Through political guile, careful alliance building, military ruthlessless and the enduring allure of a stockpile of gold, Rodrigo Díaz had earned himself the right to begin signing his name ‘The Prince of Valencia’. Now he could turn to the business of ruling.17

Despite taking over under the cloud of local dissatisfaction with the ruling class, it has to be said that the Cid’s own rule seems to have been anything but gentle. The year after his victory he had the rebellious former governor of the city, Ibn Jahhaf, burned alive for regicide and ordered the prominent citizens of the city to ransom themselves for 200,000 mithqals of gold.18 Looking to the future of his new royal dynasty, the Cid made good marriages for his daughters, Cristina and María, and, in his final years, appears to have made nice with Alfonso. This time as equals.19

After one hell of a medieval life, in July 1099, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the Prince of Valencia, breathed his last, dying comfortably in bed during peacetime at the age of approximately 56. In a little over five decades, El Cid had served countless masters, remained undefeated in battle, and carved out a lucrative principality on the east coast of Spain. Loved or loathed, this remarkable figure was compelling enough even during in his own lifetime to inspire the work of poets and chroniclers all over the Mediterranean world.

The Historia Roderici recorded his passing with words of glowing praise:

“While he lived in this world he always won a noble triumph over his enemies: never was he defeated by any man”.

Ibn Bassam concedes that:

“this man, the scourge of his time, by his appetite for glory, by the prudent steadfastness of his character, and by his heroic bravery, was one of the miracles of God”.

In France, a chronicler of Maillezais records sombre words of foreboding:

“in Spain, in Valencia, Count Rodrigo died: this was a great grief to the Christians and a joy to their pagan enemies”.

What a man, eh?

For Rodrigo, however, even death wasn’t the end of his story. What followed the Cid’s final breath was an almost uninterrupted 1000-year history of radical reinvention. Join me again soon for Part Two: Afterlives!

Did you enjoy this article? Leave your questions for me about El Cid in the comments section below and let me know if you’d like another myth-busting article on this extraordinary character. If you did enjoy this read, please consider sharing the article or telling a friend! You can also support my work by subscribing for free, choosing a paid subscription, or even leaving me the occasional ‘tip’ via Ko-Fi. Thanks for taking the time to read this article and for supporting my work. See you next time!

Further Reading

Anonymous, The Song of the Cid, (Penguin Publishing Group)

Anonymous, The Song of Roland (Penguin Publishing Group)

Roger Collins, Early Medieval Spain (Palgrave Macmillan, 1983)

Richard Fletcher, The Quest for El Cid (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991)

Bernard F. Reilly, The Kingdom Of Leon–Castille Under King Alfonso VI, 1065–1109 (Princeton University Press, 1988)

You can watch the film for free on YouTube:

Prior to the year 711, the Iberian Peninsula had been occupied by the Kingdom of the Visigoths, a successor state that formed after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The Visigoths had maintained many of the Roman structures of state, converted to Catholicism, and governed the kingdom from the city of Toledo. When 711 came around, the Visigoths were faced with a huge invasion from North Africa by the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate. Roderic, the last king of the Visigoths, was killed in the decisive Battle of Guadalete and the forces of the Caliphate quickly drove the remaining Christian leadership back into the very northern extremities of the peninsula. In later centuries, Roderic’s defeat and the destruction of Visigothic Spain came to be perceived as a punishment from God for the Visigoth’s sinful decadence.

Pope Urban II preached the First Crusade at the ecclesiastical Council of Clermont in 1095, urging the knights of Christendom to ‘take up the cross’, ride to the aid of the withering Byzantine Empire and reclaim the Holy Land for Christianity. The soldiers of the First Crusade successfully captured Jerusalem in July, 1099. El Cid had died in Valencia just five days before.

The French approach to the Islamic peoples of the Middle East, or ‘saracens’, was much more straightforward than the nuanced approach necessary in Iberia. The Chanson de Roland, a famous medieval French epic poem, dramatising the last stand of Charlemagne’s right hand man, Roland, in battle with the Saracens sums up their approach quite well: “Paien unt tort e chrestïens unt dreit”. The translation? “The pagans are wrong and the Christians are right”. And that’s that.

See Glyn S. Burgess, The Song of Roland (Penguin Publishing Group, 1990).

Another example of this strain of mildly unsatisfying evidence is Rodrigo’s carta de arras. These documents recorded the settlement of property that a man bestowed upon his wife when they married. The properties were bequeathed to the wife and her children after the husband’s death and were thus intended to provide for the family in the event of something unfortunate happening. In Rodrigo’s carta, the document lists a pretty hefty spread of properties all over Castile destined for his wife, Ximena, but the document gives no detail about the size or productivity of the lands, meaning we have no way of using it as a way of estimating the Cid’s wealth at this point in his career.

How can we possibly know this you might ask? Well, we don’t know for sure, but some brilliant palaeographers have made an educated guess. Palaeographers study old handwriting and in this case noticed some odd spelling errors where the scribe appeared to have copied the letter ‘u’ where there should have been a letter ‘a’ - like ‘Suncho’ for the name ‘Sancho’.

In the script the Historia Roderici is written in, a Carolingian script influenced by the French culture of the north, these two letters are quite distinct. However, in the Visigothic script of early medieval Spain, an ‘a’ was written with an open top, more like a ‘u’, making these letters easy to confuse for a scribe who was perhaps not well versed in both writing styles. Visigothic script began to die out in Castile before 1125 and by 1140 it was practically extinct. With this information we can hypothesise that the manuscript the scribe copied from originally was made prior to the death of the Visigothic script, perhaps itself copied from an even older original. Palaeography is like detective work. It’s very cool.

Many works of medieval literature were sponsored by wealthy patrons. If you'‘d been commissioned to write a family biography, you’d have a serious vested interest in making sure your history didn’t make your patron’s grandad look like a knob. The fact that the Historia Roderici isn’t uniformly complimentary suggests that the author might not have been intimately connected with the family. For example, the author is sharply critical of El Cid’s behaviour in La Rioja in 1092. Lamenting the wasting of the region and the terrible violence enacted against people and property, the author of this important account wasn’t afraid to slap the Cid on the wrist.

This being said, we don’t have any other documentary evidence to substantiate this claim. It could be that the anonymous author of the Cantar was originally from this area and chose to add this detail to glorify his hometown and claim the Cid for the sake of local pride.

Fighting literal wars against your own brother is less than ideal, but as you’ll see, it’s standard procedure in medieval Spain. In the 10th and 11th centuries, upon their deaths many kings divided their domains among their male children, meaning that the aforementioned male children spent the rest of their lives kicking the shit out of each other for regional supremacy.

Sancho’s death is shrouded in mystery. After losing his crown in León, Alfonso had slinked away into exile inthe Muslim kingdom of Toledo under its ruler, al-Ma’mun. Some historians have suggested, due to Zamora’s position near the frontier and the town’s association with the princess Urraca, a known supporter of Alfonso and sister to both men, that Sancho had been there to quell a rebellion or to put a stop to a planned invasion of his kingdom by Alfonso. The sources imply that Sancho’s death involved treachery of some kind, but alas, we have no more solid detail than that. Alfonso’s involvement was suspected but never confirmed and it’s impossible to tell whether such rumours were present at the time or are a later invention of the Cidian ballads.

While we cannot conclusively disprove that this happened, it seems very unlikely. The timelines don’t quite line up and the idea that a medieval nobleman of any rank had the authority to compel a divinely ordained king to swear an oath is quite out there. However, the story of the ‘Oath of Santa Gadea’ is an enduring one and makes its way into many retellings of the Cid story, including the 1961 film version.

Count García Ordóñez is one of the main antagonists in the first half of the 1961 Cid film. As we’ve mentioned, there’s certain evidence to suggest that this personal rivalry may well have been rooted in historical fact. The film ups the ante by making Ordóñez a love-rival for the hand of Doña Ximena.

There is no extant documentary evidence that suggests that Rodrigo Díaz was ever referred to by this name during his own lifetime. That being said, many scholars have theorised that the Arabic root of the nickname suggests that it could have originated while he was influential member of the Zaragozan court. What we do know is that by the time the Cantar de Mio Cid is written in the late 12th or early 13th century, usage of the nickname is obviously widespread enough that the poet can use the name ‘My Cid’ without further context and expect everyone to know who he meant.

The Almoravids were a Berber-majority dynasty that accumulated power in the mid-to-late 11th century in North Africa. More religiously fundamentalist than the generally relaxed lords of the taifa kingdoms, the Almoravids invaded the Iberian Peninsula repeatedly in the 1080s and 90s, gradually overcoming the taifas and assimilating them into a growing Almoravid Empire. Led by a Berber general called Yusuf Ibn Tashufin, the arrival of this new Islamic power in the region shifted the political dynamic significantly. Yusuf Ibn Tashufin is the historical inspiration behind the main baddie of the 1961 film, Ben Yussuf.

The Cid and Berenguer has extended and repeated beef. According to the Historia Roderici, Berenguer and Rodrigo traded insulting letters in the lead up to battles, with the Count accusing Rodrigo of sacking churches and being overly fond of auguries (prophecies based on the appearance of symbolic birds). In response, Rodrigo parroted the rumour that Berenguer had been responsible for the grisly murder of his own brother, Ramón. Players of Age of Empires II will be pleased to learn that this heated rivalry is absolutely based in historical fact.

This battle is known as the Battle of Cuarte (or Quart, in the local Valencian language). Though nothing of the Cid’s Valencia remains, the later medieval Torres del Quart occupy the same side of the old city where the battle was said to have taken place.

The charter of endowment for Valencia cathedral, written in 1098, styles Rodrigo as the ‘princeps’ or ‘Prince’ of Valencia. The fact that there is not a single mention of Alfonso in the document strongly suggests that at this point, Rodrigo’s interests are entirely his own.

One gets the sense that El Cid was very preoccupied with money. Some sources suggest that the real reason for his execution of Ibn Jahhaf was that he refused to give up the locations of the previous king’s hidden treasure. The ransom price of 200,000 mithqals of gold that Rodrigo demanded of captured noblemen equates to around £45 million pounds’ worth in modern British money.

Rodrigo married Cristina off to Ramiro, an important Aragonese nobleman, with links to the old royal family of Navarre. María was married to the new Count of Barcelona, perhaps to put an end to decades of hostility between El Cid and the Catalans. A few sources, such as the Aragonese Liber Regum c. 1200, allude to the fact that the Cid also had a son, Diego. This text records that Diego died at the Battle of Consuegra while serving in the Castilian army of our old friend King Alfonso VI. Whether this is evidence of more cordial relations between Rodrigo and Alfonso in their latter years, or a mark of a rift between father and son, nobody knows. In any case, El Cid’s royal dynasty began and ended with him.

https://open.spotify.com/track/7sJN693sYKEIEMu7fc5VnJ?si=cOI2jPSMT8egyhsTn4XlCA

Having read this, I will now proceed to watch the film and amaze people by pointing out all the bits that aren’t quite right hehe!