Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar: Death, Resurrection & Reinvention

El Cid has been reinvented since the moment of his death in 1099. Are loose adaptations just bad history, or do these legends tell us something important about ourselves?

Welcome back to Part Two of our deep dive into Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid. In Part One we tried to excavate the real man out from underneath all that myth and legend. Today, we’re going to lean in to some of the ways that these narrative embellishments have wormed their way into adaptations of the Cid’s life over the centuries, questioning what reimaginings of the Cid can tell us about the people who felt compelled to tell his story. In case you missed it in Part One, you can catch me having a conversation about precisely this on the Fetch the Smelling Salts podcast with Kim & Alice. Click here for that!

Part Two: Afterlives

“El Cid - the crusading warrior who waged wars of re-conquest for the triumph of the Cross over the Crescent and the liberation of the fatherland from the Moors. There is a disjunction here between eleventh-century reality and later mythology. In Rodrigo’s day there was little, if any, sense of nationhood, crusade, or reconquest in the Christian kingdoms of Spain. Rodrigo himself, as we shall see, was as ready to fight alongside Muslims against Christians as vice versa. He was his own man and fought for his own profit”.

- Richard Fletcher, The Quest for El Cid

*Spoiler alert*

In the final scenes of El Cid (1961), Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar is seen riding triumphantly out from the gates of Valencia, the city he had wrested away from the decadent Moorish al-Qadir just weeks before on behalf of the proud King Alfonso VI of Castile.

Accompanied by his loyal Christian and Muslim retainers, Rodrigo steadfastly holds his banner aloft, ready to lead the ethnically mixed armies of Spain against the shrieking black-robed hordes of the Almoravid general, Ben Yusuf.

The Cid’s warhorse breaks into a graceful canter on the battlefield, slowly gathering speed, and the Spanish sun in all its golden resplendence is reflected onto the armour of Castile’s most famous knight.

As the cavalry charge finally rips into the Almoravid ranks, trampling Ben Yusuf himself to death, the terrified Almoravid soldiers are scattered and driven back into the seas from whence they came. The Cid’s warhorse, stopping not for a moment, gallops along the beach, his rider rigid and motionless.

You see, the thing is, the Cid had died from an arrow injury the night before.

His men were led to victory at Valencia by a corpse.

As we all know (if you don’t, hop back and read Part One), this insane episode is a complete fabrication. Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar died of unknown causes during peacetime in his city of Valencia. If he had indeed led a posthumous sortie against the enemies of Christendom, you’d think that someone living around that time might have found it extraordinary enough to note it down.

This persistent legend, eagerly seized upon by the Hollywood filmmakers of the 1960s, however, has traceable roots that stretch as far back as to the late twelfth century.

When the monks of Cardeña received the body of the Cid after his wife’s emergency evacuation of Valencia in 1102, they set about establishing a cult of tomb-worship that amounted to a form of secular sainthood. Scholars have theorised that the sight of Doña Ximena, leading the procession of evacuees from Valencia with her husband’s embalmed body at her side, may have been gradually mangled into the folkloric legend of the posthumous charge that we have today.1

While the monastic community of Cardeña may have fostered stories about the Cid's heroic corpse to increase interest in (and therefore revenue for) their own religious institution, what attracted Bronston and Mann to this melodramatic scene in the 60s seem to be altogether different concerns.

The 1960s in America saw traumatised generations of people, scarred from the horrors of the Second World War, reach toward patriotic stories of death in the service of nation - of self-sacrifice in the face of unimaginably militant evil - to soothe the open wounds of their losses. Grief, loss and grave injury were easier to cope with if it could be re-contextualised and seen as one small part of a noble bigger picture: a wider defence of liberty and humanity itself.

At the same time, this obsessively patriotic nation was riven with divides of its own; the civil rights movement beginning to draw increasing attention to the outrageous injustices of segregated domestic society. To add an extra layer of cultural complication, the paranoia of the political class regarding the spectre of Soviet communism reinvigorated fears of a powerful, militant, and culturally alien ‘Other’ who threatened national security from beyond the sea.

What kind of hero could be more appealing than one who defended national freedom against foreign totalitarianism, bringing together Spaniards of all creeds in a final, selfless and heroic defence of their shared patria and liberty?

The opening titles of the film claim that El Cid:

“rose above religious hatreds and called upon all Spaniards, whether Christian or Moor, to face a common enemy who threatened to destroy their land of Spain”.

This bears no resemblance to the eleventh-century socio-political landscape of the Iberian peninsula. There was no such thing as a ‘Spaniard’ in the 1090s. The Cid’s alliances, made while warring against the Almoravids, were nothing more than a marriage of military convenience. This tells us little about the Cid of history. And yet it tells us plenty about the American filmmakers.

Here, the Cid of Old Castile is made a liberal, tolerant and anti-communist west-coast American patriot.

This remarkable process of cultural translation and reinvention was nothing new to the figure of the Cid. For centuries, storytellers embellished and edited his life story, with the end result depending heavily on what kind of narrative they were building, and for what purpose. When one or two inconvenient facts of history interfered with the artist’s vision, those particular scraps were swept away into the dustbin of history, or onto the cutting room floor.

The first significant re-inventors of the Cidian legend were likely the minstrels who sang the ballads of the Cid in the High Middle Ages. These travelling juglares were probably the first to grant the Cid all the trappings of a compelling folkloric hero. In an age where popular literature (even in Spain) was dominated by all-star chivalric brotherhoods like the Arthurian Knights of the Round Table2 and the Twelve Carolingian Peers of Charlemagne,3 knightly superheroes had to have all the right accoutrements to grab the interest of an audience. Enchanted jewellery, exotic Saracen love interests, named swords acquired in mysterious circumstances (like from stones and lakes for example,4 all found their place at the side of these celebrity-like figures who represented the pinnacle of martial medieval masculinity.

Within a few centuries of these popular ballads circulating, it became ‘common knowledge’ that the Cid rode a royal warhorse named Bavieca5 and charged into battle with his elegant twin blades: Tizona and Colada.6

These sung ballads that were routinely customised by individual bards began to crystallise shortly after the Cid’s death and gradually fed into larger, more ambitious, poetic works that cemented the place of the Cid in the national imagination.7

It’s these literary texts, preserved for us via manuscripts, that have provided much of the fodder for more modern re-imaginations of the Cid story too. Reinventions that have ranged widely from wrongfully-exiled feudal superstars to loveable-bad boy traitors with a mullet, and Charlton Heston playing a dead man on a horse.

Let’s get into some of those, shall we?

The Making of a Medieval Myth

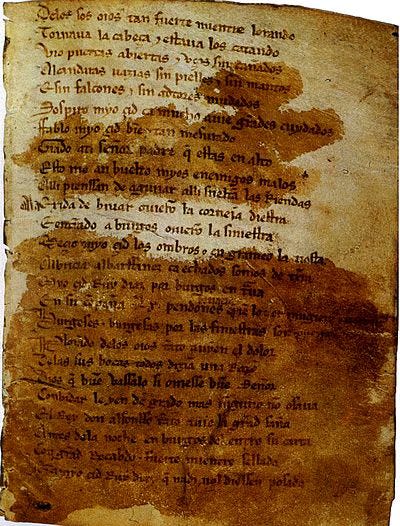

Bound in a fourteenth-century book alongside other early works of Spanish history and missing its first page, is the best known of medieval Spain’s literary attempts to grapple with the legend of the Cid.

The Cantar (or Poema) de mio Cid is the work of a gifted, imaginative, and educated anonymous poet, whose familiarity with French epic poetry and the legal codes of the Kingdom of Castile is obvious throughout the work. Though we now have to approach the poem as an incomplete written text, clues in the work indicate that, like many epics, it was originally intended to be sung and performed aloud in courtly circles.

A basic outline of the plot (as we have it) is that we meet El Cid just before the commencement of his period of unjust exile, following the hero’s journey as he traverses the Muslim borderlands of Castile and fights his way deep into enemy territory, scoring significant victories over the taifa kings and the wicked Count of Barcelona. His wandering culminates in the conquest of Valencia which redeems him in the eyes of the petty King Alfonso and he is welcomed back into the court with open arms.

Alfonso’s attempts to reward the Cid for his successes, however, turn out to be a curse. The king encourages the Cid to marry his daughters, Elvira and Sol, to the Infantes de Carrión, relations of the king himself. The Cid is sceptical, but unwilling to appear disloyal to his king, he allows the marriage to go ahead.

Only in it for the Cid’s wealth, the Infantes turn out to be cowardly little schemers who are wholly unworthy of the Cid’s noble daughters. Humiliated by the courage of the Cid time and time again in battle, and after an odd incident takes place at the palace involving a lion, the Infantes whisk their new wives away to their estates, violate them, and leave them to die in the wilderness.

Rodrigo rescues his daughters and pursues justice against the Infantes through the king’s law, teaching the king a lesson on the virtues of good judgement in the process. After winning a judicial duel and restoring the honour of his family, Rodrigo is able to remarry his daughters into the royal families of Navarre and Aragón, cementing his position at court. After many trials and tribulations, the Cid, a paragon of feudal loyalty, ties his bloodline into the royal dynasties of the peninsula and secures his legacy for generations to come.

Given that the Cantar is most likely to have been written sometime between 1140 and 1210, we might begin by asking ourselves why the author felt compelled to draw upon this particular period in Castile’s recent past for his material. After all, Castile was an action-packed place. There was no shortage of contemporary political drama for poets to work with. Why Rodrigo?

With the death of the Cid’s former master, King Alfonso VI, in 1109, things had taken a turn for the complicated in Castile. Alfonso had died without a legitimate male heir and was forced to name his daughter, Urraca, as the heir to the throne.

Urraca, being a woman, had never been intended to be a ruler in her own right. Her job was the job of medieval royal women everywhere. Urraca had to make a politically expedient marriage that secured desirable alliances for her father. To this end, she had married the prince of Aragón, Alfonso, who would go on to be crowned Alfonso I ‘The Battler’. When Alfonso of Castile kicked the bucket, Alfonso of Aragón wasn’t particularly happy with the idea of his wife ruling a kingdom in her own right. Frankly, the aristocracy of Castile and León weren’t exactly thrilled by the prospect of being ruled by a woman either.

As the first in a series of succession crises and civil wars over rival royal claims, circumstances like Alfonso VI’s heirless demise had led to major renewed tensions between the Christian kingdoms of León, Castile, and Aragon. The limited peace that had been achieved in Alfonso’s later years crumbled suddenly into the dust.

At the same time, a fresh Islamic threat loomed to the south. As the fundamentalist Almohads replaced the Almoravids and governed an aggressive empire from the Atlas mountains, their successes in battle were supported as much by Christian fragmentation and disunity as they had been by their own effective strategy.

In the midst of this chaotic state of affairs, the anonymous poet of the Cantar de mio Cid appears to have looked back upon the golden age of Alfonso VI and the Cid with a certain fondness, perceiving it as a period of relative stability, productivity and uninhibited territorial expansion. It doesn’t matter that it was actually a mess; as is often the case with nostalgia, we tend to imagine the past as better than it was.

Of course, if you’re going to invent a hero for seeing you through a moment of huge political instability, in many ways, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar was not an ideal candidate.

It’s impossible to tell how accurately the sources that the poet of the Cantar had access to told the story of the Cid and thus it is impossible to tell which deviations from the truth are down to a lack of authoritative information and which are down to creative license. In any case, the Cid of the Cantar has a much less fractious relationship with King Alfonso than his historical counterpart. Feudal order and righteous deference to divinely ordained kingship dominate the text.

Despite the fact that Alfonso is characterised in the poem as a man of ill-judgement, petty rages and poor decision-making, the Cid represents the feudal ideal of absolute loyalty. No matter what Alfonso throws at him, he is faultlessly well behaved.8

“Send me into exile? Here, have some loot I won in battle. Banish me from the court? Here, I’ll conquer the city of Valencia in your name. Want me to marry my daughters to your psychopathic nephews? Of course, sire. You know best.”

In fact the Cid says explicitly at one point:

“Whatever the King may wish, the campeador will do”.

As Richard Fletcher puts it:

“The independent, insubordinate, arrogant Rodrigo Díaz of history has been wrapped in a cloak of royalist pieties”.

Even when the Infantes de Carrión disgrace the Cid’s daughters, he seeks his vengeance through the king’s courts, not via the violent vigilante justice we know the historical Cid was quite partial to.

In the less than a century that had passed since the death of the Cid and the creation of the Cantar, the text also serves as evidence of the fact that the notion of ‘crusading’ was slowly infiltrating the Spanish consciousness. As we discussed in Part One, in the eleventh century, this foreign French ideal of Holy Warfare hadn’t really caught on in Spain. It didn’t fit with the political realities of the Iberian nobility, whose military strategies were guided more by dynastic and territorial concerns than a sense of divine duty. While El Cid fought Muslims in his career, his reasons for doing so had little in common with the French knights who took Jerusalem just days after his death on the First Crusade.

The Cid of the Cantar, however, has a more obviously religious aesthetic. Throughout, we see the Cid pray regularly for divine support in battle, cry out to Santiago (Saint James the Moor-Killer) in combat, and express a profound desire to reclaim the city of Valencia for the sake of Christendom itself, rather than for his own enrichment. Tellingly, the Cid’s service under Muslim paymasters is entirely erased from the plot of the Cantar. Muslim characters exist in the text only to submit to him, never to co-operate with him as his equals.

The sense is that as the culture of crusade gradually shaped notions of Spanish heroism more and more during the course of the twelfth century, relations between Christians and Muslims in courtly literature were necessarily more hostile. The character of Bishop Jerónimo plays a similar role to that of Archbishop Turpin in the Carolingian romances of crusade such as the Song of Roland.9 This pair of fighting bishops both offer the spiritual guarantees of the eleventh-century crusader to their warriors, affirming that should they die in combat with the infidel, their entry to the kingdom of heaven is guaranteed.

In a strangely comic episode that takes place between the Cid and a Moroccan Emir called Bucar, we can see the influence of the literature of the First Crusade on our Spanish poet even more clearly. Rodrigo pursues Bucar to the seashore after a battle and offers him a pact to ‘tajar amistad’, or to ‘strike up’ a friendship. Confused by the double-meaning of the word ‘tajar’ which can also mean ‘to cut’, Bucar cries “God confound such a friendship!” and is promptly sliced in half from the head to the waist, replicating a common motif in poetic retellings of the First Crusade wherein Godfrey of Bouillon cuts saracens in two left, right and centre.10

Despite this, even when reimagined as a French-ified crusading superstar, the Cid’s approach to his Muslim adversaries continues to reflect concerns particular to Spain’s political reality.

In a debate about what to do with Muslim prisoners of war, the Cid argues:

“We gain nothing from beheading them … for we are their lords.

We shall stay in their homes and put them to good use”11

Recognising that Muslims are a large proportion of the local population, the Cid appreciates that decimating them isn’t really an option here. He even goes as far as to excuse their military aggression:

“We are in their lands and are doing them every possible wrong…

If they come and besiege us, they have every right.”12

appearing to acknowledge a certain degree of Islamic ownership over the lands of Spain.

Comparing this approach with the famous lines of the Song of Roland: “the pagans are wrong and the Christians are right”; it is clear that the Spanish text, produced in an environment where Christians and Muslims still co-exist, embodies a distinctive nuance.13

El Cid: The Multiverse

The fact that the Cantar survives in only a single, incomplete manuscript makes it hard to estimate how popular the text was in aristocratic circles. Nevertheless the poem, or at least the subject matter it described, seems to have been well-known enough to quickly inspire later works Cidian literature.

Far from being copycats, however, the resulting works were sometimes significantly different. Around the year 1360, another epic poem was written about the Cid, now known as the Mocedades del Cid, or the ‘Youthful deeds of the Cid’. In this barnstormer of an epic, the measured, considered and poised Rodrigo of the Cantar is replaced by a destructive, testosterone-fuelled force of nature in the form of a reckless teenager.

The poem is even further removed from reality than the Cantar too, with the rebellious Rodrigo eventually starting and winning fights with (to name a few) the Holy Roman Emperor, the Count of Savoy, the King of France and even the Pope himself. Produced in a period marked by unstable kingship in Castile, the epic is far more concerned with inter-Christian tensions than interfaith ones and appears to endorse moderate baronial disobedience in circumstances where kings are perceived to be failing in their duties of leadership.14

One thing introduced by the Mocedades that proved to be transformational to later legends was the notion of the young Rodrigo killing the father of his bride-to-be, Ximena. In the medieval text, this killing occurs in response to Count Gómez, Ximena’s father, insulting Rodrigo’s family honour. He is then forced by King Fernando to marry Ximena to ensure that she is well taken care of.

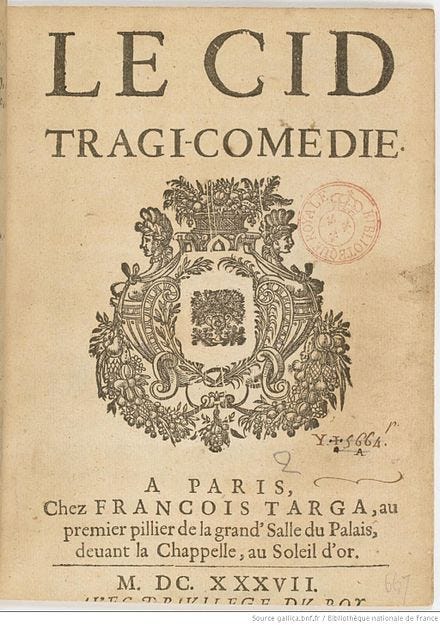

As literary tastes gradually became less graphically violent and more sentimental in the sixteenth century, this plot point began to be represented as part of a wider tragic love story between the Cid and Ximena, with the Cid, already betrothed to Ximena in many versions, having to choose between defending the honour of his father and the life of his future father-in-law. Used to address complex debates around the conflict between personal desire and familial or social duties, this element of the legend became extremely popular. In the early 1600s, dramatic adaptations of the Cid, such as a 1605 play by Valencian playwright Guillén de Castro, began to be adapted in French-language works, propelling this intensely Spanish hero into the broader cultural consciousness of early modern Europe for the first time.

A 20th Century Legend: El Cid in the Modern World

Sword fights, fair maidens, and legendary horses are all well and good, but how is it that the Cid, with his emblematically medieval story, was able to maintain his appeal in the modern age?

By the time the 1960s came around, Spain had already had a busy and bloody twentieth century. The traumatic ruptures of the civil war in the 1930s had been concreted over by the gloomy militarism of General Franco’s fascist regime and for the next two decades due to European instability and political persecutions, things had been pretty bleak. On the international stage, Spain’s post-war status remained deeply uncertain.

During the early years of Franco’s government, Spain looked as fragile as it had ever been. In some sense, this disjointed nation patched together from disgruntled and disparate linguistic and cultural minorities was still as loosely knitted together as it had been under the bullish Castilian kings of the Middle Ages. Modern Spain, dominated by the central regions that had been born of the Cid’s Old Castile, was a still a fragile thing - like a castle built on sand.

In this brittle environment, Franco and his closest advisors looked to Old Castilian heroes like the Cid as an analogy for their own recent victories. For Franco, the Cid had been one of his own: a military strongman who, through Catholic devotion and personal charisma, had begun the centuries-long process of bringing together the kingdoms of Spain into a united polity, ruled from the centre in Castile.

The idea that the Cid had somehow hastened the unification of Spain, though completely divorced from reality, was an old one. The final lines of the medieval Cantar, celebrating the marriages of Elvira and Sol into the royal houses of Navarre and Aragón, affirm:

“now the kings of Spain are of his line

and all gain honour through the man born in a favoured hour”.

Aside from being positioned as the father and forger of the same nation Franco had just forced back together at the barrel of a gun, Franco’s version of the Cid purged the peninsula of the malign foreign influences of Islam in much the same way that Franco liked to imagine he was purging the nation of the wicked machinations of republicans and communists.

The regime’s enthusiasm for the Cid was apparent from the outset. In 1937, a government-sponsored journal was established in Burgos, near the Cid’s birthplace, with the stated objective of raising the stature of this national hero. General Aranda, a Francoist who served as captain general of Valencia, shortly after the civil war had explicitly compared his success at the grisly Battle of Teruel to the Cid’s conquest of the Spanish Levante.15 Around the same time, the well-known equestrian statue of the Cid in Burgos was popped up onto his pedestal for the first time.

In this context, it is perhaps no surprise that when big-time American film producer Samuel Bronston established his own production studio in Madrid in the 1950s, Franco’s government advocated hard for their national hero to be brought to life on screen. Bronston, perhaps trying to strengthen his cordial ties with the ruling class, accepted the proposition, hired Anthony Mann to direct, and shooting promptly began on a colossal joint American-Spanish-Italian production in 1960.16

Replete with romance, battles, jousting and melodrama, Bronston and Mann successfully communicated elements of Franco’s Spanish ideal to an enormous international audience. Elevating medieval Spain to an exotic land of adventure, heroes, and fantasy; the film was dynamite for revitalising Spain’s bruised post-war international image.

It’s also fair to say, however, that in some respects Franco got rather different outcomes than he bargained for. While the film unquestionably celebrated the courage and piety of Franco’s Catholic hero, Charlton Heston’s Cid also embodied the cultural and religious tolerance of an American liberal - an outlook on national diversity that didn’t sit entirely well with Franco’s ruthless and repressive regime. Marked by merciful interactions with Moorish emirs and a touchingly faithful relationship with his Muslim compatriots, it is hard to imagine that General Franco was thrilled when Heston’s Cid delivered the line: “you’ll make a Muslim of me yet” to his close ally, Moutamin.

Rather than using the Spanish setting to ruminate on the origin myths of the Spanish state for Franco’s sake, like many works of Cidian art before it, it is clear that the Hollywood film instead took advantage of the distant past in order to pass comment on current affairs. In the case of 1960s America, this included the continued tensions of the Cold War and the gathering intensity of the civil rights movement.

The contemporary moral messages of the film are most clearly communicated through the villains of the piece. Ben Yusuf, wild-eyed and cloaked in black robes, is presented as the enemy of civilisation (as characterised through the Western lens, of course) and it is easy to interpret his fevered speech about conquering Spain and then the whole world as a nod to the anti-communist ‘domino theory’ that dominated the American Red Scare.17 As Moutamin, the Cid’s ally, expresses his fear for the future of Spain under the Almoravid threat, he evokes the imagery of nuclear war, predicting: “war, death, and destruction: blood and fire more terrible than has been seen by living man”.18 In Ben Yusuf’s totalitarianism, militarism, and aspiration toward world domination there is very thinly veiled allegory for the perceived threat of Soviet communism at the height of the Cold War.

Not the only bad guy in the story, Ben Yusuf is matched in his obstinate intolerance by King Alfonso, who froths at the mouth when Rodrigo proposes an alliance with the friendly Moorish emirs in order to drive back the Almoravids.

“This is a Christian kingdom, we treat only with Christians”

- is his frosty response to the plan.

Ultimately, though he avoids the fate of Ben Yusuf, Alfonso’s pride and refusal to treat with the other side bring him and his people to the brink of oblivion. Left standing alone at the Battle of Sagrajas, Alfonso is brutally defeated. El Cid, on the other hand, leading a mixed army into the siege of Valencia is successful, noting to Moutamin that:

“we have so much to give to each other and to Spain”.

Rodrigo’s final position as the saviour of an ethnically mixed and united Spain perhaps conveys the sense of possibility and hopefulness that progressively-minded Americans, supportive of the civil rights movement, yearned for in their own country. The filmmakers’ conviction in the righteousness of the cause can be observed within the heady optimism of Rodrigo’s joyous embrace of Islamic hospitality at the court in Zaragoza. Watching his men laugh and feast with those of Moutamin, he puzzles aloud:

“how can anyone say this is wrong?”

Moutamin: cautious and contemplative, offers the knowing response:

“they will say so, on both sides”.

Life, Death and Resurrection

“The reason I wanted to make El Cid was the theme ‘a man rode out to victory dead on his horse’. I loved the concept of that ending”

- Anthony Mann, March 196419

As interesting as it is to examine how iterations of the Cid have differed according to the historical circumstances of their creators, it is equally as productive to recognise fascinating examples of continuity. For all the world has changed in 900 years, thirteenth-century monks and twentieth-century Hollywood directors were often interested in similar things.

Here, I think the death of the Cid and the subsequent adventures of his lifeless corpse deserve special attention.

Bronston and Mann’s Cid is an pseudo-saintly figure. In exile, unable to accept help from the local peasants, lest they be punished by Alfonso, a parched Cid offers the last of his water supplies to a leper called Lazarus.20 At the beginning of the film, Heston’s Cid aids a priest in rescuing an effigy of Christ on the cross from the smouldering ruins of a church, carrying the cross away over his shoulder, replicating Biblical images of Christ himself bearing the cross to the site of his crucifixion.

Choosing an avoidable death to save the lives of his men, the Christ-like El Cid is sacrificed for the sake of a shared ideal, being reborn the next day to lead his men into one final battle - a judgement day, if you will. As the deceased body of the Cid leads his final charge, the Spanish sun bathes his upper body in light, crowning our hero with a gleaming halo of gold.

This hallowed twentieth century scene of a saintly warrior riding into his own myth and legend would have been entirely familiar to the brothers of the monastery at Cardeña in the thirteenth-century.

In April 1102, as the Almoravid general, Mazdali, encircled the city of Valencia, the city’s sole ruler, Ximena Díaz, widow of the great El Cid, had evacuated the city. Setting fire to the town before abandoning it to the enemy, Ximena packed up the city’s archives and riches, taking with her the most precious treasure of all: the embalmed body of her beloved Rodrigo.

Heading to Cardeña, a monastery that had benefitted greatly from the continued patronage of the Cid and his wife, Ximena laid the Cid to rest, joining him in a shared tomb around the year 1116. Keen to celebrate their noble patron, capitalise on his celebrity, and secure privileges for their house, the monks appear to have set about producing stories of the Cid’s alleged saintliness almost immediately.

It seems that the interest of the great medieval Castilian King Alfonso X ‘El Sabio’ (‘the Wise’) in the story of the Cid might well have been inspired by a visit to Cardeña in 1272 when the monks gifted him a now-lost volume of stories on the life of their Cid. These stories, incorporated into the great chronicles sponsored by Alfonso’s learned court, give us interesting insights into the kind of myths that were being perpetuated at this time.

In one story, an envoy from a great Sultan of Persia arrives at the court of the Cid with gifts of a fine chess set, balsam, and myrrh. Having accepted the gifts, St. Peter (the Patron saint of Cardeña) appears to the Cid and tells him though he will die in 30 days, God loves him so much that he’ll grant him victories after death.

In another, rather more grim, story a Jewish intruder who infiltrates the monastery seeks out the body of the Cid, which in this version has been embalmed and on display in the church for ten years.21 Wanting to get one over on this long-dead Christian hero, the Jewish mischief-maker approaches the body and tries to pluck a hair from his beard, at which point the Cid’s body reaches for his sword. In response to the terror of this miracle, we are told that the Jew converted on the spot and served the monks of Cardeña for the rest of his life. Evidence of the continued influence of these stories attributing semi-miraculous deeds to the Cid in death continues into the early modern period with King Philip II even petitioning the Pope to have the Cid canonised in 1554.22

Though these stories might seem terribly silly and macabre to use these days, they strike me as embodying a very human desire to elevate national figures that represent the ‘best’ of a community’s shared values onto a higher plane of existence. These stories represent a recurrent heroic paradox that those who are capable of extraordinary things are simultaneously ‘one of us’ but are also uniquely blessed by the powers that be. They are at once the ultimate embodiment of shared ethical codes that good citizens must aspire to emulate, but they are also something else. They are beyond quotidian understanding - something that the Average Joe can never hope to equal.

Are these medieval stories of secularised sainthood a million miles away from the morbidly stirring spectacle of Charlton Heston playing dead on a horse? I'd argue that they aren’t.

As the deceased Cid rides into the sunset in the Hollywood movie, we are supposed to recognise that he represents the best of men, a symbol of individual exceptionalism, alongside something bigger than that: a Christ-like instrument of divine will. Neither the medieval nor twentieth-century representation of such secularised sainthood is that far removed from the archetype of a contemporary Marvel superhero. Superheroes, as we encounter them in the 2020s, tend to be ‘normal’ people with outstanding morals who, through a combination of their own ability and blessed accident, are elevated above their peers. They are our culture’s chosen ones in much the same way as the Cid was for the nobility of medieval Spain.

Ultimately, despite centuries of human development, heroic figures who speak to our communal values and aspirations, remain as alluring in 2024 as they were for King Alfonso X in 1272, reading his book on the Cid at Cardeña.

Rodrigo Díaz, mio Cid, el Campeador

“This man of combat is a ‘combat concept’: an adaptable figure of thought that travels beyond its original historical referent to help societies represent their worlds through the imaginative engagement with another”

- Julian Weiss, El Cid (Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar)

Much in the same way that each human society conspires within itself to create monsters that embody its deepest fears, each generation of participators in the Cid’s versatile legend took it upon themselves to fashion him into the hero that their individual society required.

For the anonymous author of the Historia Roderici, this desirable ideal was a successful mercenary who proved to the ambitious baronial class that ascendance through military success was an achievable goal in times of political chaos. For the composer(s) of the Cantar de mio Cid, it was a faultlessly loyal vassal: stoic and cool-headed, who exhibited a winning combination of saintly patience and fierce martial skill. For the fascists of Franco’s Spain, the Cid was the original unifier of the Spanish nation, a role which he never played, nor even aspired to, during his lifetime.

For the booming and extravagant Hollywood of the 1960s, El Cid was a glossy icon of modern masculinity who reflected a progressive American patriotism, championing racial integration and tolerance in the face of an exotic evil.

And for us? Who is our El Cid? As I write this in the year of our lord 2024, it looks like he’s a moderately hot desperado with a questionable mullet and inconsistent morals, who’s sexually liberated, frustratingly chaotic, and prone to getting tied up against his will in the intrigues of the court.23 Once again, as art detaches from the historical reality in some respects ever further, some elements of this most recent Cidian evolution bring the character more closely towards the rollercoaster events of eleventh-century Rodrigo’s lived realities.

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar’s life as a historical human may well have ended almost a millennium ago in July, 1099, but his afterlives are showing no sign of slowing down any time soon.

Did you enjoy this article? I want to hear what surprised you about El Cid the most. Leave your comments for me down below! If you did enjoy this read, please do consider sharing the article or telling a friend! You can also support my work by subscribing for free, choosing a paid subscription, or even leaving me the occasional ‘tip’ via Ko-Fi. This content takes a while to put together and your kind donations allow me to keep doing it! Thanks again for taking the time to read this article and for supporting my work. See you next time!

Further Reading

Anonymous, The Song of the Cid, (Penguin Publishing Group)

Anonymous, The Song of Roland (Penguin Publishing Group)

Roger Collins, Early Medieval Spain (Palgrave Macmillan, 1983)

Richard Fletcher, The Quest for El Cid (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991)

Mark Jancovich, ‘The Purest Knight of All: Nation, History and Representation in “El Cid” (1960)’. Cinema Journal. Vol. 40, No. 1. pp. 79-103.

Anthony Mann, "Empire Demolition". Films and Filming. Vol. 10, No. 6. pp. 7–8.

Bernard F. Reilly, The Kingdom Of Leon–Castille Under King Alfonso VI, 1065–1109 (Princeton University Press, 1988)

Julian Weiss, ‘El Cid (Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar)’ in The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the Crusades, ed. by Anthony Bale, (Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 184–99.

Once again, Age of Empires II players, I’m sorry if you feel cheated by this revelation. I feel your pain. Defending the Cid’s deadass corpse-on-a-horse from Yusuf’s Navy, Army and Black Guards in the final campaign scenario was a CHORE.

Everyone in medieval Europe was obsessed with King Arthur. Ever since Chrètien de Troyes created the first significant cycle of Arthurian romances in the twelfth century, chivalric ballads, romances and epic poems all over Europe either revolved around an Arthurian character, or had cameos from them. The list of Knights of the Round Table is unstable and depends on which sources you consult, but you’ll be familiar with the big hitters: Lancelot, Gawain, Galahad, Percival, Bedivere, Tristan etc.

In the same way that Marvel and DC Comics create their own loosely adapted versions of each other’s characters depending on what sells well, the popularity of Arthurian legend led to other subjects being reimagined and written about in a similar way. The Frankish King Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor (crowned in the year 800), quickly became another hugely popular protagonist in medieval epic literature. Closely echoing the idea of Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, Charlemagne was given 12 (somewhat fictional) ‘peers’ or ‘paladins’ who accompanied him on various adventures. Their names were Roland, Oliver, Gérin, Gérier, Bérengier, Otton, Samson, Engelier, Ivon, Ivoire, Anséis & Girard. Popular Carolingian side characters also include Archbishop Turpin (a particularly violent take on a Friar Tuck vibe) and Ogier the Dane.

Looking at you, Excalibur.

Bavieca features in lots of retellings of the Cid and there are several associated legends about how he acquired him/her (Bavieca is gender fluid - depends which legend you read). In the very early Carmen Campidoctoris, a horse is given to the Cid as a gift from a ‘barbarian’, probably meaning a Muslim in this context. Later legends are more ambitious. One suggests that a knight on horseback challenged the Cid to a duel in order to become King Sancho’s champion. King Sancho, wanting it to be a fair fight, granted the Cid the use of Bavieca, a fine warhorse from the royal stables. Another story claims that as a gift upon his coming-of-age, Rodrigo’s godfather, a monk, allowed him to pick a mount from a herd of well-bred Andalusian horses. Feeling that his godson had picked the ropiest, gangliest, and weakest charger of the lot, he exclaimed ‘babieca!’ which means ‘stupid’. Legend has it that the young Cid was so amused, he named his precious new horse ‘Babieca’.

Tizona (or Tizón) and Colada both feature in the Cantar de mio Cid. Swords that claim to be Tizona and Colada are also on display in Spain at various museums. Metallurgical analysis of Tizona did show that it was cast in eleventh-century Moorish Córdoba, but the likelihood that either of these swords were ever actually gripped by the hand of the Cid is… not high.

For example, a fragment of poetry survives from c. 1147 (around 50 years after the death of the Cid) which contains the line: “ipse Rodericus, Meo Cidi saepe vocatus / de quo cantatur quod ab hostibus hand superatur”. In English, this translates to: “This Rodrigo, often called my Cid, of whom it is sung that he was never defeated by enemies”. By referring in the way that he does to the fact that Rodrigo is a character well known in song, our educated Latin poet builds a picture of a popular culture where ballad singers are using the Cid’s story quite often.

In this way, the 1961 film draws quite closely on the Cantar’s characterisation of the relationship. The film version sees a wise, loyal and contemplative Rodrigo having to grapple with an immature, impulsive, petty and proud Alfonso. Alfonso’s character arc throughout the movie sees him gradually absorb from the Cid all the qualities of good leadership and, by the end, he appears to have the makings of a successful king. Despite the 800 years or so between them, the two representations have much in common.

ICYMI in Part One, the Song of Roland is a game changing early text in the French epic tradition. It tells the story of Charlemagne and his boys going on a mini Crusade into Spain. Their rearguard is ambushed by Saracens in the Roncesvalles Pass and the heroic Roland, Charlemagne’s right hand man, fights valiantly until his heroic death. This tale of Christian sacrifice is heavily influenced by the ideology of the First Crusade.

This might seem oddly specific but stick with me on this. Godfrey of Bouillon, one of the leaders of the First Crusade, became a kind of chivalric celebrity after the successful capture of Jerusalem. According to various reports, none of which are hugely trustworthy, at some point during the Holy Land campaigns Godfrey cut a huge saracen warrior in half by the sheer might of his sword blow. This legend blows up in ballads sung of the First Crusade and all of a sudden, a quick way to make someone seem heroic in your poem was to have them replicate Godfrey’s famous feat. That appears to be what’s happening here.

Line 621-22 of the Cantar de mio Cid.

Line 1103-5.

Despite the ethical binaries that the Song of Roland appears to promote, these texts that deal with inter-cultural conflict were often used to ask complex questions about the nature of nobility in a frontier society. While the Muslims of the Roland story are all clearly “wrong” in their religious practice, some of them are praised for their martial skill or their bravery. In fact, the biggest baddie in the whole thing is Roland’s Christian uncle, Ganelon, whose treachery assures Roland’s death.

Similarly, in the Cantar, Rodrigo’s friend Abengalbon is a Moor who is praised regularly for his noble and courageous conduct. It is he who discovers the treachery of the Christian Infantes de Carrión and reveals their plot to Rodrigo in a loyal act of service and submission.

The Mocedades was birthed during more civil strife and instability. A bloody civil war between King Pedro I and his half-brother Enrique de Trastámara came to an end in 1369 when Enrique literally stabbed Pedro in the back at a diplomatic summit. This catastrophic war was aggravated by the involvement of foreign powers including the French and the English who used it as a proxy battlefield during the Hundred Years’ War. This was a time of foolish kings, powerful nobles, and long-running aristocratic blood feuds.

The Battle of Teruel was an extremely bloody battle in the Spanish Civil War fought between December 1937 and February 1938. Casualties on both sides amounted to around 110,000.

You can watch the film for free on YouTube here:

The ‘Domino Theory’ was the fear that if the USA allowed Soviet communism to spread to one country in a region, the rest would also fall ‘like dominoes’ into the Russian sphere of influence. The term ‘Red Scare’ was used to describe the moral panic in the USA provoked by the fear of Soviet communism infiltrating domestic leftist politics.

The representation of the burning town that El Cid arrives to rescue right at the beginning of the film is also somewhat reminiscent of images of Hiroshima & Nagasaki after the detonation of the American nuclear bombs.

See Mann, Anthony (March 1964). "Empire Demolition". Films and Filming. Vol. 10, No. 6. pp. 7–8.

For those who didn’t go to Sunday school, Lazarus was the name of a man in the Bible who was resurrected by Jesus after four days of death. The name perhaps forebodes the Cid’s own death and ‘resurrection’ of sorts at the end of the film.

Medieval Spain was an extremely anti-semitic place. Unfortunately, Jews are often the bad guys in these stories of transgression and conversion. Medieval Spanish anti-semitism culminated in the forced expulsion of the Jews in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs, Fernando and Isabél.

Spoiler alert, the Vatican wasn’t having it.

You can check out the most recent attempt to bring Rodrigo Díaz to life by watching El Cid, the Legend on Amazon Prime. It’s a decent Spanish series with a minor Game of Thrones vibe that reflects a 21st century desire for nuance and flawed or tortured heroes. But be warned, the mullet really is terrible.

Does it bother you that most people will only ever know the versions we see in these series/films, and not take the time to look into the real story? Or do you think there’s value in whatever knowledge these types of channels provide?