‘Drunk Beyond Measure’

Overindulgence can have all sorts of unintended results. Ask these guys...

Happy New Year everyone! Thanks for continuing to support me and my work through into 2024! Today, we’ve got a Dry January themed post to kick off the year together. As always, if you enjoy this post, please consider liking or sharing the article, leaving a comment, or subscribing for free to join the community. It’s very much appreciated.

January. People seem to either love it or hate it, don’t they? For some the fizz of excitement that comes with an opportunity to start afresh carries them through the coldest and darkest days of the winter. For others, surviving those bleak nights necessitates semi-hibernation under layers of fleece and a never ending supply of hot chocolate. Whichever kind of person you are, it’s often a time when people think about taking extra care of themselves. That’s where Dry January comes in, I guess.

I have been teetotal for almost 4 years, but I’m not going to use my little corner of the internet here to wax lyrical about how euphoric sober nightclubbing can be. Instead, I’m hopefully going to give all those giving Dry January a whirl this year some extra motivation to make it to the 31st of the month by telling you about some drunken historical disasters.

Basically, if you find yourself tempted to reach for a cold one after a long day, just remember that alcohol can lead to all manner of mishaps…

One hell of an AirBnB bill…

In 1698, Tsar Peter the Great of Russia was on a gap year. A truly visionary kind of tyrant, Peter’s passion project was to bring the vast Russian Empire more in line technologically and culturally with western Europe through huge infrastructure projects and reforms, no matter the monetary or human cost.

One thing he happened to be particularly keen on was boats and, amongst other things, building Russia’s first great navy was high on his extensive list of priorities. The only problem was that Peter, nor any of his closest advisors, knew anything much about boat building at all. At this point in his early reign he hadn’t even built his great coastal fortress city of St. Petersburg yet and Russia lacked the skilled craftspeople to oversee Peter’s desired nautical revolution.

Perter’s solution was to gather his squad of confidantes and organise a ‘Grand Embassy’ to bop around Europe for a while, stopping in countries with more advanced technologies and seeing what he could learn from them. Having already spent a good deal of time picking the brains of the Dutch East India Company in the Netherlands, on the 11th January 1698 he arrived in London, England, with a party of four chamberlains, some interpreters, his cook, an Orthodox priest, 70 Russian palace guards, two clock makers, four dwarves and a monkey.

His English itinerary was pretty packed: Peter met King William III, received an honorary doctorate from Oxford University (like many celebrities before and after him), attended scientific lectures at the Royal Society, and even spent time studying astronomy at the Greenwich Royal Observatory. But the highlight for Peter was of course being permitted to observe the Royal Navy fleet reviews in Deptford.

Enter John Evelyn’s early modern AirBnB.

John Evelyn was a founding member of the Royal Society and was relatively well known as a minor government official, a keen gardener, writer, landowner and courtier. Evelyn owned a house in Deptford which he had sublet to Vice-Admiral John Benbow who, in turn, decided to sublet the swanky townhouse to the visiting Peter the Great.

That was a mistake.

Peter was lively, a hard drinker, and a massive 6’8. After long days out quizzing the brightest sparks in the Royal Navy about their ships, Peter threw enormous parties in Evelyn’s house to help him unwind and they very frequently spiralled out of control. Consuming truly staggering quantities of hard spirits in ways that perhaps only eastern europeans can (without literally dropping dead), Peter’s rowdy gang ended up smashing up 80% of Evelyn’s furniture to use it as firewood, using valuable family portraits for pistol target practice, breaking windows, and flattening several of the house’s grand interior doors. The whole thing was very ‘large Russian bull in small English teashop’ vibes.

As a final kick in the teeth for poor John Evelyn, Peter also managed to ruin some hedges in the gardens that had taken Evelyn 20 years to grow and shape. The shrubs were reportedly damaged by night after night of drunken wheelbarrow racing. The wheelbarrows didn’t make it either.

Horrified by some of the worst house guests in history, Evelyn’s steward wrote to him in a panic and Evelyn promptly organised for his friend Christopher Wren and the royal gardeners to pop in and assess the situation. Wren’s report estimated the total damage at £350 which, in today’s money, might have been as much as £480,500.

Ouch.

Don’t Drink and…Ride?

Alexander III was a king of Scotland in the 13th century and was the last crowned monarch of the House of Canmore. On the night of the 19th March 1286, Alexander had been celebrating his second marriage with his pals and advisors at Edinburgh Castle, reportedly enjoying a substantial amount of his favourite tipple (Bordeaux wine in case you’re wondering) during the course of the evening.

As the night wore on and the party got merrier, the weather conditions outside were deteriorating drastically. However, despite the howling wind, fog and rain of a coastal storm, Alexander remained fiercely determined to make it back to the nearby fortress at Kinghorn in Fife before the next morning in time to celebrate his new queen’s birthday together that following day.

With ominous clouds gathering over the sea and nobles muttering their panicked disapproval, the party set off for Fife in the dark. Perplexed by Alexander’s stubbornness (or perhaps his drunken feeling of invincibility…) one of his companions, Alexander Le Saucier, reportedly exclaimed: “My lord! What are you doing out in such weather and darkness? How many times have I tried to persuade you that midnight travelling will do you no good?”

Hell bent on ignoring the sound advice of his riding party, Alexander was eventually separated from the others in the confusion of the tempest, disappearing without a trace in the dark of the night.

The next morning Alexander’s body was found alongside that of his horse at the foot of a rocky crag on the treacherous coastal pathway. Though some chronicles of the time claimed that the horse had simply spooked in the storm and that even such a fine rider as Alexander would have been powerless to avoid the tragedy, more than a few medieval writers of Scottish history claimed that Alexander’s erratic drunken horsemanship might have been more likely to blame for his death.

Alexander’s untimely death and the ensuing succession crisis sparked a series of unfortunate events that culminated in the First War of Scottish Independence and the deaths of thousands of people.

Do not drink and drive kids. Book a Travelodge.

Bar fights can escalate quickly

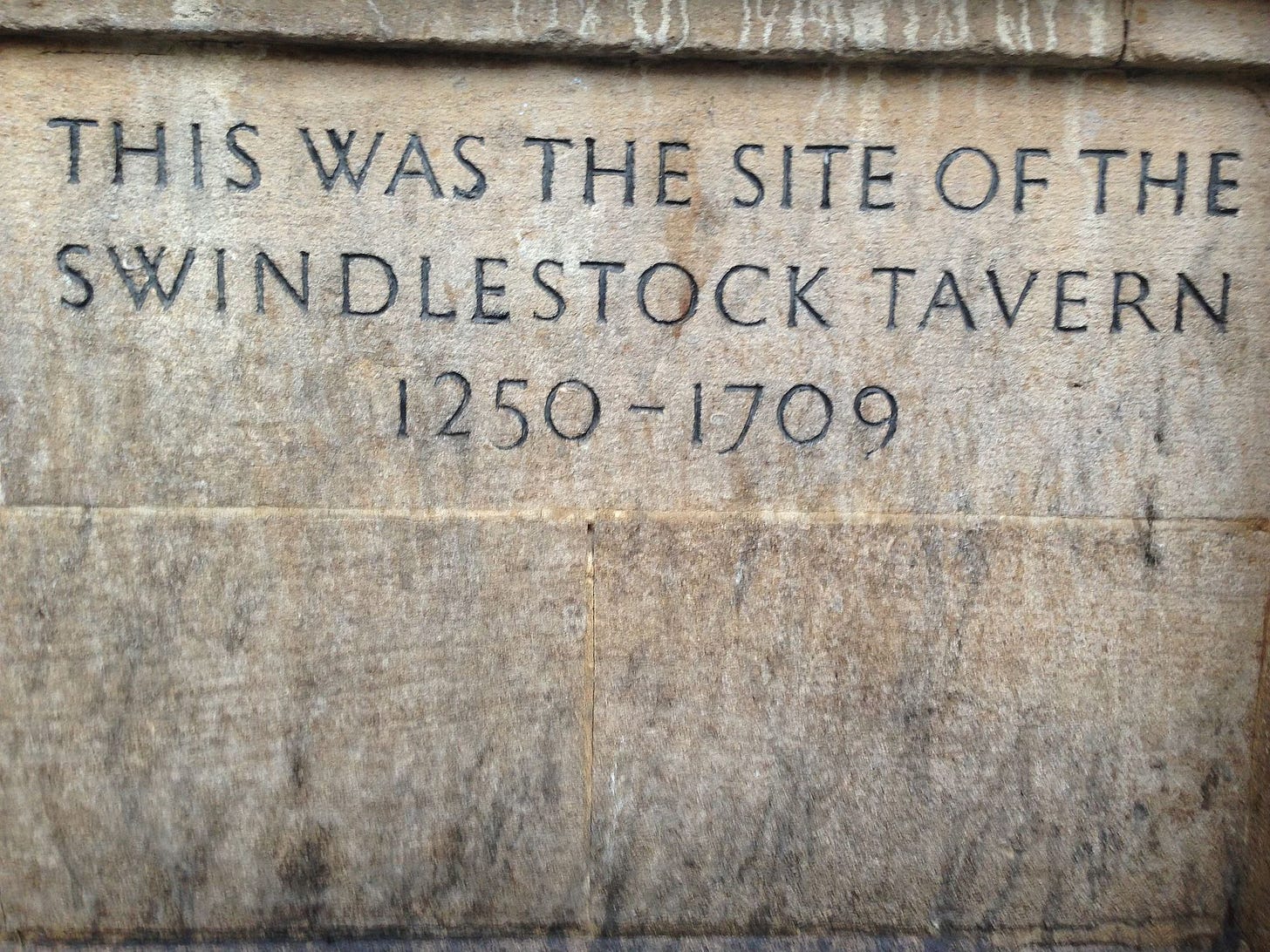

On the 10th of February 1355 (St. Scholastica’s Day), a group of Oxford University students wandered into the Swindlestock Tavern in the centre of town looking for a drink. A well-established watering hole for students of the university, the Swindlestock was owned by John de Bereford who was also the town’s mayor, meaning it was the hangout of choice for most of the senior townspeople in Oxford too.

Having sat down and made themselves comfortable, two of the Oxford students, Walter de Spryngeheuse and Roger de Chesterfield, expressed their displeasure at the quality of the wine served to them by the taverner, John de Croydon. Not having any of it, de Croydon batted away their rude complaints before "several snappish words passed" between them. As tensions escalated in the tavern with neither side backing down, the students reportedly blew their fuse when de Croydon came back at them again with "stubborn and saucy language”. What happened next depends on who you were talking to.

Those sympathetic to the university claimed that de Chesterfield simply threw his wooden drinking cup in the direction of de Croydon’s head. Those chroniclers more sympathetic to the townspeople alleged that he wrestled de Croydon to the floor and beat him repeatedly with a pot.

Now that blows had been exchanged all hell broke loose. Tensions between the university community and the townsfolk were often high which might frankly sound familiar to people who study at Oxford or Cambridge even now.1 In this case, the underlying resentments against the haughty students boiled over and other customers on both sides of the conflict joined in the scuffle until it became a fully fledged bar brawl.

Rather than seek to deescalate the situation, both sides raced to summon backup, each ringing church bells to alert others to the fight. Before long, what started as a scrap over shit wine had snowballed into a town-wide riot that lasted a whopping THREE DAYS. Armed gangs from rural villages descended on the town to back the townspeople who then broke into the university halls, murdering the inhabitants. Teaching university clerics were even scalped in their chambers.

The Chancellor of the University, Humphrey de Cherlton, attempted to broker a peace between the two warring factions before things spiralled even further out of control but was forced to retreat when a flurry of arrows were pointed his way. All in all, the riot claimed the lives of approximately 30 townsfolk and 63 members of the university.

Finally, King Edward III had to get involved to restore order. He sent royal judges to the town to ascertain who was guilty of starting and escalating the violence and they came down firmly on the side of the university authorities. Though perhaps very unfair, this isn’t surprising. As educated and ‘well-bred’ types, the university scholars were always going to win out over the commoners of the townsfolk. The town authorities were fined a massive 500 marks and some of its senior officials were jailed in Marshalsea prison in London. Oxford was even made subject to a year’s long internal ‘excommunication’ of sorts called an interdict, banning all religious services including marriages and consecrated burials.

And that’s not even it! Every year on St. Scholastica’s Day, the anniversary of the riots, the mayor, bailiffs and townsfolk were forced to attend a mass at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin for those scholars killed in the violence and made to pay a fine of a penny for each of them. This practice only came to an end in…1825.

Be nice to servers and make good choices. Saucy language can have consequences that last for 500 years.

Electric lighting = Game-changing for boozers

Almost everything about daily life was more hazardous in the medieval period including getting drunk. For some poor unfortunate souls, it was fatal. On the 22nd June 1297, Margery Golde, an inhabitant of the English city of Oxford got … (and I quote the medieval coroner’s roll directly) … “drunk beyond measure”.

We’ve all been there.

Tragically for Margery, she got so wasted that she fell asleep forgetting about the lit candle that she had fixed to the walls of her home. As the candle burned down, embers fell onto the straw of her bed and the rushes that were customarily used as flooring in medieval houses immediately burst into flame.

The records tell the story as follows:

“It came to pass on Saturday before the feast of the Nativity of St. John-the-Baptist, in the 25th year of King Edward, that Margery, wife of Adam Golde, died in her house where she abode, in the parish of St. Peter-in-the-East, and immediately she was viewed by Adam de Spalding, coroner. An inquest was held thereon the same day before the said coroner by means of the four neighbouring parishes, to wit, St. Peter’s-in-the-East, St. Mary’s, St. Mildrid’s, and All Saints; and all the sworn men in that inquest say upon their oath that on Friday last the said Adam Golde and Margery, his wife, had been at a tavern, and were drunk beyond measure, and at night when they went to bed the said Margery fixed a lighted candle on the wall by their bed, and both entered their bed and left the candle burning and immediately fell asleep; and when the candle had burnt as far as the wall, that which remained fell on the straw by their bed, and burnt it and the said Margery even to the belly, whereof she died on the next day, but she had all church rights. Asked whether the said Adam her husband could have saved her from the fire, so that she could have lived, they say upon their oath that he could not, because that the same Adam scarce escaped his own death, for that his hand and feet were burnt to the bones, so that scarce will he recover.”2

Grisly stuff. The teachable moment from Margery and Adam’s tale of woe here above is to avoid lighting up your Yankee candles when you’ve been out getting rowdy with the lads. This advice is as valid in the 21st century as it was in the 13th.

A 12th century piss-up to civil war pipeline

William the Aethling (sometimes written William Adlin) was the only legitimate son of King Henry I of England and was serving his father as Duke of Normandy in his own right at the tender age of 17. In November of 1120, Henry, William, and the rest of the royal court had been on a diplomatic visit to France and, after the conclusion of the negotiations, were making their way back toward the English Channel to return home. King Henry was keen to get back to England as soon as possible and his ship set sail in the late afternoon. William’s party, on the other hand, were travelling separately on a ship that would end up departing hours and hours later.

Why? Well, William was a party animal and, according to some near contemporary chroniclers, he was stubborn, pampered, spoiled, bulshy, and wild. The party gathered at the harbour and got riotously drunk with the sailors due to sail them home, draining barrels and barrels of ale and wine before finally boarding their vessel together for the channel crossing. Chronicler Orderic Vitalis claims in his account that the vibe amongst the 300 passengers was so lairy that they recklessly “drove away with contempt, amid shouts of laughter, the priests who came to bless them” and “were speedily punished for their mockery”.

William’s boat, the White Ship, was known as the finest and the fastest that the English navy had. It was also captained by a man with a reputation: Captain Thomas FitzStephen, whose father had famously captained the ship that brought William the Aethling’s grandfather, William the Conqueror, over from Normandy in the invasion of 1066.

Fuelled by drunken arrogance, FitzStephen claimed that despite the hours-long delay caused by their impromptu piss-up, the White Ship was so fast that it would easily overtake the vessel of King Henry who had departed hours ahead. Urged on by the cheers of the intoxicated prince and his noble pals, the feverishly drunk crew threw caution to the wind and rowed furiously fast out of the harbour in the darkness of the night.

Unfortunately, in their inebriated state, the crew failed to keep a sufficient lookout and turned the ship into a hazardous stretch of water peppered with submerged rocks. One such rock tore a gaping hole in the hull of the White Ship and within minutes all but one of the 300 passengers, including William the Aethling, had met their watery end in the freezing cold sea.

Orderic Vitalis’ breathless account of the tragedy powerfully juxtopposes the mindless aristocratic vanity of the prince’s party with the humility of the sole survivor of what came to be known as ‘the White Ship Disaster’. The last man standing was a peasant butcher called Berold, who managed to make it back to shore in one piece to deliver the devastating news of the Aethling’s demise.

William’s drunken hubris and his tragic death had very far reaching consequences for England. With no remaining legitimate male heirs and his queen being of too advanced an age to produce new ones, a grief-stricken King Henry was forced to depart radically from tradition and name his daughter Matilda as his sole heir.

Despite being extremely well-qualified for the job as the capable widow of the Holy Roman Emperor, the idea of an all-powerful woman like Matilda on the throne went down like a lead balloon with the 12th century English aristocracy. Upon Henry’s death in 1135, most of them abandoned their pledge to recognise Matilda as the queen and instead hastily crowned her cousin, Stephen of Blois, as king of England.

Amazingly, Stephen himself was only available for crowning thanks to … a bout of diarrhoea. Stephen had been one of the many young bucks involved in William the Aethling’s wild party at the harbour and was due to travel to England with him on the White Ship. Unbelievably, he drank so much that he made himself violently ill with diarrhoea and thus decided to stay ashore, probably saving his own life.

Matilda didn't take Stephen’s usurpation lying down and gathered her supporters together to try and claim the throne that was rightfully hers. This clash began a period of brutal civil war in England known as The Anarchy which only came to an end when Stephen agreed to recognise Matilda’s son, Henry Plantagenet, as his heir. Henry became king in 1153 upon Stephen’s death and his Plantagenet dynasty would rule until 1485.

So there you have it! Hopefully these tales of historical death, damage and disaster will help to give you the motivation you need to stay off the mead a little while longer. You’ve got this! And if you have any encouraging tips for those giving sobriety a try, drop them in the comments below!

Did you enjoy this article? If so, I have a small favour to ask of you! Please hit the ‘like’ button and leave a comment below on which facts surprised you the most. If you know someone who might find this article interesting - share away! And please subscribe for free with your email so that you never miss a new post. Your likes, comments, subscriptions and shares all help the blog get seen by more eyes which in turn gives me the space, resources and reach to create bigger and better content for you all. Thank you for all your continued support.

The grotesque town vs. gown divide that still resonates in Oxford and Cambridge even now has a long history. Violent disagreements between townspeople and students in Oxford had arisen several times previous to the St. Scholastica Day riots. In fact 12 of the 29 coroners' courts held in Oxford between 1297 and 1322 concerned actual murders committed by lawless students. Interestingly, the University of Cambridge was established in 1209 by scholars who left Oxford fearing for their safety following the lynching of two students by the town's disgruntled citizens.

Thoroughly enjoyed that, Clara. Relations in Oxford between ‘town and gown’ have a long history, but that brawl takes some beating, lol! For me, the only drunken cockup that compares with the White Ship is that of Shakespeare’s birthday binge with Ben Jonsson. I’ve often wondered whether his life might have been prolonged had he stayed home that night.

On the lighter side of drinking, one story I’ve always enjoyed is that of poor Sir Thomas Blount, who was hanged, drawn and quartered for his role in the Windsor Plot against Henry IV. On being asked by his executioner after his disembowelling if he would like a drink, Blount replied, ‘no, you have taken away wherein to put it.’ Pure brilliance!