The Legend of St. Valentine(s…?)

What have medieval martyrs, beekeeping and talking ducks got to do with romance?

Love it or hate it, Valentine’s month is upon us everyone! Today, we’re taking a look at the saint(s) behind the heart-shaped chocolate boxes and the hastily-bought bouquets of flowers. As always, if you enjoy this post, please consider liking or sharing the article, leaving a comment, or subscribing for free to join the community. By referring the Substack to your friends, you can also earn benefits for any sign ups using your referral link. More on that here.

Now, I’m willing to bet that on February 14th you’ll probably be doing one of two things.

Half of you, both singletons and those who are happily coupled up, will use this most famous of saints days to celebrate all things LOVE. Whether it’s taking your significant other out for a candlelit dinner, or celebrating the shit out of your closest friends, for many, the Feast of St. Valentine is the perfect opportunity to hype up those you care about and make them feel just a little bit special.

As for the other half of you, I’m guessing you’ll be staying in, scranning pizza, muting your social media for the night, and chatting with likeminded friends about what a heap of commercialised bollocks Valentine’s Day really is.

What I think we can all agree on is that V-Day is BIG. It’s everywhere.

Over the course of centuries of celebration, this obscure saints day has become a cultural and commercial heavyweight. But who actually was the Saint Valentine at the root of all this? Why was he associated with love in the first place? And what the hell have talking ducks got to do with any of it?

Let’s dive in…

The St. Valentine we know and love was more than one person (probably)…

Due to a serious lack of surviving sources, reconstructing the biographies of the early Christian martyrs is always a pretty complex task. In the Late Antique period1 ‘Valentine’, or ‘Valentinus’ in Latin, was a very popular name2 derived from the word ‘valens’, meaning strong, worthy or powerful. With this in mind, it hardly seems surprising that there was more than one Christian martyr recorded by this name.

So, what are the sources for our Valentines?

Accounts contained within some of the earliest Christian martyrologies appear to point to at least three ‘Valentines’ who died as Christian martyrs in the Late Antique period: Valentine of Rome, Valentine of Terni, and a Valentine who was martyred alongside companions in North Africa.3 Though we know next to nothing at all about the North African Valentine, the Valentines of Terni and Rome have semi-distinguishable martyrdom stories, albeit still lacking much developed biographical detail.

To complicate matters, however, even the most notable early martyrologies are light on evidence and were produced considerably after a possible Valentine’s lifetime. The famous Roman Chronography of 354 doesn’t include a Valentine on a list of martyrs venerated on specific dates, but does suggest that Pope Julius I built a St. Valentines Church during his pontificate (337-352 AD), offering evidence of a growing saints cult of some kind around a martyr carrying this name.4 A Valentine is also attested in later copies of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum5 which might have been put together sometime between 460 and 550 AD, up to three centuries after the death of our possible Valentines. Though it might well have been based on authentic earlier local sources now lost to us, it is also likely that various parts of the text were added much later as it was continuously updated. Hagiographical texts were very fluid.

From what we can make out from the available sources, St. Valentine of Rome was a priest who ran into trouble with the Roman authorities in the usual way; by preaching to the pagans and converting an inconvenient number of Romans to his blossoming underground Christian cult. This Valentine reportedly died around the year 270 AD and was beheaded on the Via Flaminia outside of Rome. It is this version of Valentine that is recognised by the official Roman Martyrology of the Catholic Church, giving his feast day as February 14th.

As for Valentine of Terni, according to the records that chronicle the history of the Terni diocese, Valentine was a bishop who was born in the Roman settlement of Interamna, living there for most of his life. The brief details concerning his life story claim that in 269 AD he was imprisoned, tortured and eventually killed while staying in Rome temporarily on the orders of the Emperor Claudius II on (you guessed it!), the 14th February.

Now, the eagle-eyed among you may have spotted the various similarities between these two accounts. Both men reportedly are killed under the reign of Claudius II (268-270 AD), both are essentially punished for being annoying Christian preachers, both meet their grisly end on the outskirts of the city, and both at some point came to be associated with the date of February 14th. This shared “nucleus of fact”6 between the Valentines of Rome and Terni have led some scholars to convincingly argue that they were the same man, with later medieval records offering conflicting biographical notes that caused their legends to diverge.

Ultimately it is quite impossible to know whether St. Valentine was a case of multiple real people being smushed together into a single narrative, or the total reverse: where a single real person provided the source for multiple conflicting stories and traditions that developed over the centuries since his death. In practice, this exceptionally hazy origin story has meant that Valentine became the kind of saint upon whom different attributes and legends were projected at different times.

St. Valentine’s legend is properly fleshed out as the medieval period goes on…

By the High and Late Middle Ages, the various versions of St. Valentine had been well and truly mashed together and his biography (which had more holes in it than Emmental cheese) had been more fully fleshed out with legend.

Compiled in around 1260, the Legenda Aurea (‘Golden Legend’)7 of Jacobus de Voragine gave a brief version of Valentine’s life story wherein the Emperor Claudius became enraged having gotten wind of Valentine’s repeated refusal to deny Christ and stop preaching amongst the population. Before being executed by beheading, Valentine miraculously restored the hearing and sight of his jailer’s sick young daughter.

Echoing similar themes, hagiographical texts of the later Middle Ages, like the encyclopaedic Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) a text of mammoth ambition, tell versions of a more in depth account claiming that Valentine, an exceptionally well educated Roman priest, was held under house arrest in the home of a judge called Asterius before his execution. Allegedly, over the course of many days discussing religion, Asterius became increasingly curious about Valentine’s Christian worship and set him a challenge to prove the validity of his faith. He brought Valentine his blind adopted daughter and pledged that if Valentine’s God could cure the child, he would repay him however he wished. Predictably, (if you’ve ever read a hagiography) Valentine succeeds and the little girl was able to see again after Valentine prayed and rested his hands over her face.

The result of this massive coup for Jesus in the Asterius household was that the judge, his daughter, and around forty of his servants were all baptised immediately, with all Christian prisoners being promptly released into the wild. Sadly though, this moment of triumph was followed by the familiar ending. Valentine’s extraordinary successes in the conversion department put a target on his back and he was beheaded on the Via Flaminia after a heated argument with the Emperor about idol-worship.

We owe Valentine’s Day as we know it to Geoffrey Chaucer and some chatty birds…

Ah Chaucer. The Father of English Poetry and one of the non-negotiable guests at my hypothetical ‘dead-or-alive’ dinner party. Now, we’re not suggesting here that Geoffrey invented the feast day of St. Valentine, but rather that the specific association that the day now has with all things love only emerges after our Geoffrey mentioned it in one of his poems.

The Parliament of Fowls, written c. 1375, is quite a mad and brilliant poem narrated in the form of a dream vision. We could talk for hours about the classical and Dantean references it makes, or even the politically complex commentary it offers on civic humanism, the common good of society and class hierarchies, BUT I’m not going to bore you all with that here. Another time perhaps…

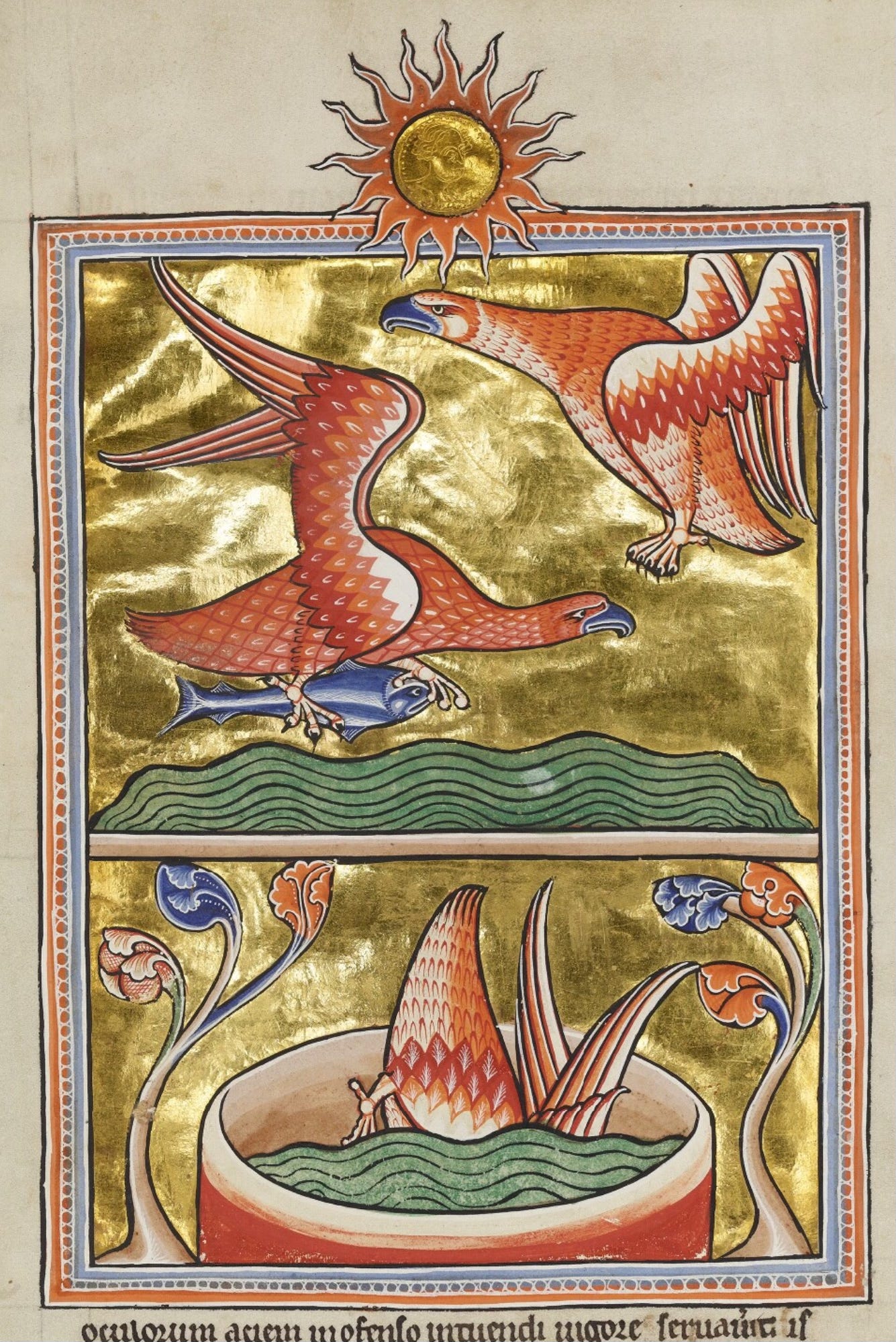

Beginning as a meditation on art, love and ‘common profit’, the poem’s narrator is transported through a dark Temple of Venus, decorated with tales of doomed lovers, as he falls asleep, and then emerges into bright sunlight where the goddess Nature has been called upon to settle a debate. Nature finds herself surrounded by a cacophony of birds (including some very rude and disruptive ducks) who have all gathered together to choose their mates. Being of higher status than the rest of the birds, three male eagles each present their case as the best candidate for the hand of a sexy female eagle at great length, much to the chagrin of the other birds who are not permitted to pair off until the eagles have made their choice. Hoping to hurry the eagles along so they can get to shagging, the rest of the birds launch into a heated and comical debate that explores free will, societal sacrifice and all sorts of other quite serious issues despite being laced with puns and extraordinary innuendo. Eventually the female eagle decides she doesn’t want to get married after all anyway and flies off, leaving the lower status birds to pair of as they choose and sing a song welcoming the arrival of spring.

Why is this weird poem about birds relevant, I hear you ask?

Well, the birds, gathered for the express purpose of finding a lover, meet on the feast day of a certain saint…

And in a clearing on a hill of flowers

Was set this noble goddess, Nature;

Of branches were her halls and her bowers

Wrought according to her art and measure;

Nor was there any fowl she does engender

That was not seen there in her presence,

To hear her judgement, and give audience.

For this was on Saint Valentine’s day,

When every fowl comes there his mate to take…8

With this single line, Chaucer cemented an association that survives to this day.9 While some have argued that rather than inventing this connection out of thin air, Chaucer may have been building upon existing practices that linked Valentine to fertility and romance, the truth is that there’s really no evidence of this. At this point scholars still haven’t been able to find a convincing record of romantic celebrations on Valentine’s Day that pre-dates Chaucer’s dream vision of argumentative birds.

By the 1400s, the association of St. Valentine with lovers and affianced couples had taken root amongst an aristocracy who were frankly obsessed with the mega-popular literature of courtly love. The social allegory10 within Chaucer’s own work had partially laid the foundations for this sudden boom in popularity through its careful symbolism. The magnificent eagles at the centre of the Valentine’s Day debate speak with immaculate courtly manners that reflect popular works of aristocratic literature and are almost certainly intended to represent the noble classes within the societal microcosm the world of the birds represents. These eagles - polite, poetic and powerful - reflected the poem’s readership: they were a mirror to the affluent nobility and aspirational figures to the literate members of society who aspired to such noble status.

Inspired by the massive popularity of Chaucer’s poetry11 (especially once it was circulated in print), nobles increasingly began to exchange tokens or letters of affection on Valentines Day, a practice that was recorded in the work of several 14th and 15th century poets.12 A moving and personal example of this survives in the Paston Letters, a collection of correspondence between members of the Norfolk-based Paston family and their associates.

Writing to her choice of wealthy suitor, John Paston III, expressing her desire to seal a match for her daughter, Margery, Lady Elizabeth Brews wrote:

And, cousin mine, upon Monday is Saint Valentine's Day and every bird chooses himself a mate, and if it like you to come on Thursday night, and make provision that you may abide till then, I trust to God that ye shall speak to my husband and I shall pray that we may bring the matter to a conclusion.

Later, Margery herself wrote a letter to John addressing it:

“unto my rightwell beloved Valentine, John Paston Esquire"

The fresh new link between Valentine and romance quickly leaked from popular secular poetry into hagiographical legend too. Later accounts of the life of Saint Valentine(s) written in the post-Chaucer period increasingly added details to the biography that spoke to this theme. One account, for example, had Valentine as a temple priest who got in trouble with the law primarily for helping Christian couples marry in secret.

But Valentine is not all about love, you know…

Medieval saints tend to have a hefty workload in their afterlives. As people pray to them through their relics, they are expected to take an active interest in worldly affairs and entertain these petitions on behalf of the needy, heading upstairs to have a word with the big man to see whether they can sort out a miracle for you.

These days we know St. Valentine as the patron saint of love and everything that goes with it - such as affianced couples and happy marriages, but as we've just discussed, this patronage of all things romantic only began to emerge from the 14th century onwards. St. Valentine has jurisdiction over so much more than just that!

Oddly, Valentine is also a patron saint of mentally ill people, plague, epilepsy, travel, fainting and … beekeepers.

There’s so little evidence to conclusively prove precisely how Valentine came to be associated with these various things, but the likelihood is that his associations with plague, epilepsy and fainting are the longest standing. It was common for medieval saints and their relics in general to become associated with healing miracles, meaning that a whole variety of saints were connected with various ailments after one or two well publicised incidents of someone being cured by praying to them. It was also common for these associations to then be superimposed onto the saint’s own life story. Later legends of Valentine of Terni, for example, retrospectively credit him with curing a Roman orator’s son of epilepsy.

Furthermore, around the time of Valentine’s death, a huge pandemic occurred in the Roman Empire called the Plague of Cyprian which, at its height, was reportedly killing 5,000 people a day in Rome. It is possible that aside from preaching, Valentine, like many early Christian leaders, was tending to the sick and needy and that the memory of this somehow survives through the legacy of his cult. Ironically, after Valentine’s execution, the Emperor Claudius II who ordered his death also caught the plague and died.

Regarding the beekeepers … I don’t know what to tell you. It seems totally random. Our best theory is that bees, often revered as a symbol of fertility, might have become associated with Valentine around the same time he was first linked to love and springtime in the 14th century.

You can go and visit St. Valentine if you’re so inclined…

If you’re feeling particularly goth while on a romantic trip to Rome, you can go and visit Valentine himself (maybe)… As in the case of most medieval saints, the cult of St. Valentine grew over centuries around the veneration of his relics, the most impressive of which is (allegedly) Valentine’s severed head, kept in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Rome.

Adorned with a crown of flowers, this gnarly skull was supposedly exhumed from the excavation of a Late Antique catacomb outside of the city in the 1800s. With a mere 1500 years having flown by in between Valentine’s last breath and the discovery of this crispy old skull, it is worth mentioning that the 19th century in Italy saw a bit of a trend develop in terms of digging up old dead people and labelling them as lost saints. Though such claims to saintly and historical authenticity were unlikely to be accurate, it didn't stop the trade in relics being as lucrative a business as it had been in the Middle Ages themselves.

As is customary for the mortal remains of holy men, fragments of St. Valentine(s) have actually ended up all over the place. If you don’t fancy the flower-crowned skull, you could instead pay tribute to his shoulder blade, discovered in a church basement in Prague in 2002, or, alternatively, bits of … another skull of St. Valentine in Chelmno, Poland. For those looking to stay closer to home, you could catch a glimpse of some blood and bone of his in Whitefriar Street Church in Dublin or Blessed St John Duns Scotus in Glasgow.

And there you have it, a little bit more about the patron saint of red roses and fully booked restaurants in February. I hope that whatever your plans this evening, you’ve enjoyed learning a little bit more about how we got here in the first place! Felicem Diem Valentini! Happy Valentines Day!

Did you enjoy this article? If so, I have a small favour to ask of you! Please hit the ‘like’ button and leave a comment below on which facts surprised you the most. If you know someone who might find this article interesting - share away! And please subscribe for free with your email so that you never miss a new post. Your likes, comments, subscriptions and shares all help the blog get seen by more eyes which in turn gives me the space, resources and reach to create bigger and better content for you all. Thank you for all your continued support.

‘Late Antique’ is quite a fuzzy term but generally we use it to describe the awkward period in between the end of the Classical Age and the beginning of the Middle Ages ‘proper’. This usually equates to the late 3rd century up to the 7th or 8th century in Europe and around the Mediterranean. In reality, ‘Late Antiquity’ and ‘Early Medieval’ often enjoy some crossover, but with the latter only really being used after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD.

There was even a Pope Valentine, though little is known about him for sure except that he served a mere 40 days as the Pontiff around 827 AD.

This excellent blog provides a detailed breakdown of all of the earliest sources for St. Valentines of all kinds! Explore it here.

Excavations on a site approximately one mile outside the gate on the Flaminian Way (where Valentine was reportedly beheaded) have revealed what appears to be the ruins of a fourth century church basilica. Archaeologists believe it to have been centred on an early fourth century memorial which could feasibly have been a martyr’s grave. For more on this, see Michael Lapidge, The Roman Martyrs: Introduction, Translations, and Commentary (2017), p.423. You can preview the relevant bit here.

This translates to ‘St. Jerome’s Martyrology’ although it was almost certainly NOT originally written by St. Jerome. Some 8th and 9th century manuscripts of the text mention a feast day for Valentine, but it cannot serve as useful evidence for when the cult was established or for details of Valentine(s)’ life. See an interesting discussion of the documentary evidence here.

See the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 1983), p. 1423.

The Legenda Aurea of Jacobus de Voragine was one of the most frequently copied and read books of the High Middle Ages. It contained 153 hagiographies (saints’ lives) written in Latin and was intended to serve as a saintly encyclopaedia of sorts for those who needed material for composing sermons. The text remained absurdly popular for centuries. In the 15th century, the text became one of the first books ever to be printed in English, with William Caxton publishing his own translation of the work in 1483.

This is a translation with modernised spelling, the original spellings of this crucial part of the poem would have looked like this: “For this was sent on Seynt Valentyne’s day / Whan every foul cometh ther to choose his mate”.

Interestingly, some scholars propose that Chaucer wasn’t thinking about February 14th when he mentioned the Feast of St Valentine in the Parliament of Fowls, but rather May 3rd, the feast day of a later Saint Valentine of Genoa. Chaucer travelled to Genoa in the 1370s while working as a diplomat and possibly came to know of the local saint during that time. This argument is bolstered by the fact that elsewhere in medieval literature, May is a month frequently associated with the birdsong and the blossoming of the natural world. These scholars argue that people retrospectively assumed he meant the February date as St. Valentine of Rome was more widely known in England than his Genoese counterpart. After all, February is still a little cold to be thinking about Spring…

That being said, with February being the month in which plenty of winter flowers make themselves known, it isn’t inconceivable that Chaucer felt the February date was a suitable harbinger of warmer and brighter times.

An allegory is a story, poem, or image that can be interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning. That meaning is typically moral, social or political in nature.

Without a doubt, the best edition of Chaucer’s texts is the Riverside Chaucer. Buy it here and PLEASE read some Chaucer. It’s a hoot. (*affiliate link).

The Ballades of the bilingual poet, John Gower, written in French and the work of John Lydgate supply several examples of this. By 1415, the association was beginning to travel to other parts of Europe too. The French Duke of Orleans, imprisoned in the Tower of London, called his wife in his correspondence “ma doulce Valentine gent” (my sweet gentle Valentine).