St. Nicholas of Myra: The Life & Times of a Medieval Santa Claus

Will the real Saint Nicholas please stand up…?

Happy Christmas Eve! Welcome to the second of the December Substack specials! Today we’re discussing the big man in red, Santa Claus himself: or, if you’re a medieval person, that’s St. Nicholas of Myra to you. As always, if you enjoy this post, please consider liking or sharing the article, leaving a comment, or subscribing for free to join the community. It’s very much appreciated.

Santa, Mr Claus, Father Christmas, Saint Nick, Sinterklaas… Whatever you call the old fella dressed in red who delivers your pressies for Christmas morning; each iteration of our wholesome festive grandpa-figure can trace their origins back to a real historical person - Saint Nicholas of Myra (c. 270 - 343 AD) - one of the medieval world’s favourite saints.

Beyond the knowledge that Nicholas was born in around 270 AD in the city of Patara (in modern-day Turkey), we actually don’t know a huge amount for sure about Saint Nicholas’ real life. Though there are numerous extant later accounts of his miraculous exploits, there is very little reliable evidence from which to construct a firm picture of the historical Nicholas or even to piece together the early history of his cult and veneration.

However, despite some glaring gaps in our understanding of precisely why it came about, we know that St. Nicholas became unbelievably popular in the early Middle Ages. Celebrations of Nicholas varied from region to region, but a sustained interest in his life and miracles across the centuries led to a dynamic and developing legend that gradually coalesced around so much of what we recognise in the figure of Santa Claus today. Things like charity and generosity, his patronage of children… and even leaving the odd citrus fruit in your stocking!

Here are 5 interesting facts about the life, miracles and cult of the REAL Santa and how the medieval period took him from an obscure Turkish bishop to a bona fide seasonal superhero…

Santa’s native language was Greek

Patara, Saint Nicholas’ hometown, was a port city on the Mediterranean Sea in what used to be known as the Eastern Roman Empire.1 The empire hugged the eastern coasts of the Mediterranean, occupying much of modern day Greece, Turkey and Egypt, and was home to a population that was more strongly influenced by the Hellenic culture of the Greeks than the predominantly Latin-speaking empire of the West. Though the ancient city is within the territory of modern Turkey, the Turkic-speaking nomads whose language would come to dominate the region hadn’t yet migrated to the area.

Nicholas was born into a family of Greek-speaking Christians who we can safely assume were relatively wealthy. The education level necessary to rise to the bishopric would have been highly untypical of anyone who had grown up in a more humble background and early written legends surrounding St. Nicholas support this. Several versions of his life recount that upon the sudden death of his parents in an epidemic of disease, St. Nicholas (being very devout) chose to redistribute their wealth among the poor rather than keep it for himself.

Furthermore, it seemed that religious service itself was in the family, as Nicholas’ uncle had seemingly served as the Bishop of Myra during Nicholas’ childhood, doing the exact same job that Nicholas would go on to do for most of his life.

St Nick might have attended a very famous conference

The period of late antiquity (the time of transition from the classical world to the Middle Ages) was a hugely important time for the growing Christian communities of the late Roman world. Jesus and the OG disciples weren’t that long gone in the grand scheme of things and factors such as scattered leadership, ongoing Roman persecution, and a lack of standardised religious texts left the intellectuals in the Christian flock grappling with exactly what being a Christian actually meant, both in theory and in practice. This period of widespread debate on the organisation of the Christian world is referred to as the Patristic Era, during which time the Church Fathers (standout Christian theologians) worked to establish the doctrinal foundations of the new religion.

The nitty gritty details of these doctrinal disputes were worked out at huge meetings of clergy that brought together various sects who then argued their conflicting cases. One of the most famous of these gatherings was the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. Without getting too neck deep into Christian theology, this council was convened to debate Arianism2 which was an idea that had been developed by a group of Christians who argued that the Holy Trinity (God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit) was a hierarchical structure, with God sitting on top of the tree. Opponents of this proposal, the Trinitarians, argued that the three aspects of the Trinity were all God in equal parts. Long story short, they won the debate and the Arians were somewhat ostracised as heretics.

St. Nicholas is said to have been one of the many bishops who attended this influential gathering and signed the concluding Nicene Creed, declaring his fervent support for the Trinitarians. Though impossible to prove for certain, this is certainly plausible. Such councils were attended by hundreds of delegates and an early record of those present compiled by Theodore the Lector claims that Nicholas of Myra was the 151st attendee. While St. Nick is often not listed on any of the shorter lists of attendees, and is conspicuously absent from the accounts of some influential Trinitarians, Athanasius of Alexandria and the historian Eusebius, he does feature on a total of three full lists of Nicene delegates. Some have argued that this suggests that although Nicholas may have been present, his participation in the conference wasn’t considered particularly consequential.

An alternative possibility that enjoys significant scholarly support is that he did not, in fact, attend at all but that his name was intriguingly added to lists at a later date. Though this might feel like a let down (stick with me) - it’s fascinating. While at the time of the Council of Nicaea Nicholas of Myra may have just been one boring Greek churchman among many, not senior enough to have received an invite to the theology showdown of the decade, in the Middle Ages St Nick’s reputation skyrocketed.

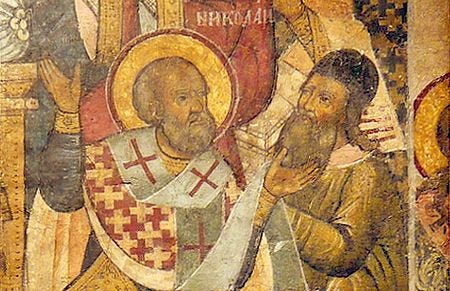

Educated medieval people were fairly obsessed with the lives and careers of the Church Fathers and judgements like the Nicene Creed were perceived as formative moments in the history of the Christian community. It might be that as Saint Nicholas’ cult gained increasing popularity in medieval Europe (more on that later), writers concerned with his story chose to lend him additional prestige by inserting him into the Nicaea narrative. Retrospectively adding him to the guest list was one thing, but some medieval writers even went as far as to invent dramatic episodes concerning Nick’s conference appearance, including 14th and 15th century accounts that describe him becoming so consumed with Trinitarian passion that he bitch-slapped Arius (the leader of the Arians) across the face. This story became so widespread that it even became a common image in religious art.

Stories of Nicholas’ miracles began his association with young people

One of the key representational transformations that reshaped St. Nicholas, the late-antique churchman, into St. Nicholas, the nice old man who brings you gifts at Christmas, is when he began to be strongly associated with children.

The origins of this association are in the medieval accounts of Nicholas’ early miracles. The most famous story of this kind tells the tale of a man with three young daughters3 who didn’t have the money to give each of them a dowry. This was a mega problem.

In the Eastern Roman Empire, a decent dowry was required for women to make a suitable match and to be able to secure a comfortable life through their husband. Women who didn’t have access to this were at risk of being forced into work in the brothels of the imperial cities in order to survive after the death of their male relatives.

St. Nicholas was disturbed upon hearing of the girls’ plight, but was too modest to provide financial assistance out in the open and feared humiliating the already-proud father. Working around this conundrum in a most ingenious way, St. Nicholas decided to visit the house under the cover of darkness and sneaked a coin-filled purse through an open window. The next day, the flabbergasted father immediately used the money to arrange a marriage for his first daughter. The next night, Nicholas left a second bag of coins for the second daughter, and finally, the next night, a third bag of cash for the youngest. With all three girls hastily married off, Nicholas had spared them a life in the brothels, never taking any credit for doing so.4 This is the first example of St. Nick being presented both as a protector of young people and as a kindly figure who delivers gifts secretly at night out of generosity and compassion. As the depiction of this story became more and more widespread in Christian iconography, the bags of coins were sometimes substituted for alternative gifts that nodded towards St. Nicholas’ ‘exotic’ origins in the East, such as loaves of spiced bread, jewels and even oranges. The iconographical convention of including oranges and other citrus fruits in portrayals of St. Nicholas may even have had something to do with the much later development of a tradition of leaving oranges or tangerines in children’s stockings at Christmas.

St. Nicholas worked a great many miracles in his time. So many, in fact, that he became known as Nicholas the Wonderworker. In another fantastical instance of being the medieval version of the NSPCC (looking out for children everywhere), St. Nicholas managed to save three children from being literally made into ham.

The story claims that during a disastrous famine, a butcher lured three boys into his house (Hansel & Gretel style) where he killed them and popped their bodies in a barrel of salt - fully intending to cure the meat and sell it off as ham. Luckily, Nicholas was in the area, ministering to the hungry, and learned of the butcher’s terrible crime. Busting into the butcher’s house and discovering the murder-barrel, St. Nicholas made the sign of the cross, blessed the room, and managed to miraculously resurrect the three pickled kids.

And that, my friends, is how you seal becoming the patron saint of children.

St Nicholas’ skeleton has been THROUGH IT

Like many medieval saints, the growth of the cult of St. Nicholas was inextricably linked with the fascination surrounding his mortal remains - or, his ‘relics’. In medieval Christianity, relics were extraordinarily powerful objects through which to interact with the spiritual realm. Praying with the relic of a saint was tantamount to calling a heavenly hotline, giving you a direct channel through which to ask for some divine solutions to your problems. Aside from being sacred and revered objects of religious devotion, on a more cynical level, saints’ relics were an excellent boost for regional economies, attracting pilgrims from all over Christendom to visit the holy sites associated with their favourite celebrity saints. Pilgrims would sometimes feel compelled to donate directly to the religious communities that housed the relics, but would have at the very least boosted local businesses as they procured supplies and accommodation along their journey, meaning that there were tangible economic, political and societal benefits to being the keeper of a saint’s well-known corpse.

We don’t know everything we’d like to about how St Nicholas’ cult began to gather steam, but as early as the beginning of the 5th century (less than two centuries after his death) we have evidence that his saintly reputation had reached the ears of the emperor. Emperor Theodosius II (r. 401 - 450 AD) reportedly ordered the construction of a Church of St. Nicholas over the site of the saint’s tomb and later, in the rule of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527 - 565 AD) several churches dedicated to St. Nicholas in Constantinople (the capital of the eastern empire) were renovated at great expense. The enormous financial outlay for these projects speaks to a rising local popularity and probably reflects earlier localised veneration of St. Nick that we don't have any clear material evidence for.

Having laid happily in the land of his birth for around 700 years, becoming the focus of a thriving local cult, St. Nicholas' body was then the victim of a scandalous religious robbery.

In the 11th century, things were kind of going from bad to worse on the Anatolian peninsula. The once-great Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) was crumbling away under the pressure of repeated invasions from the Seljuk Turks, who had migrated west from the steppes of Central Asia. The bloody Battle of Manzikert in 1071 saw the empire temporarily lose control over most of Asia Minor to the Seljuks, also therefore losing sites of religious significance to the Greek Christians, including St. Nicholas' hometown of Myra.

At the same time, a great big barney between the Catholic Church in the West and the Greek Orthodox Church (the ruling church of the empire) over who was in charge of who and the ‘right’ way to do things, meant that Christians in the West became suddenly very concerned that access to the pilgrimage sites in the former empire would become more tightly restricted.

The tomb of St. Nicholas had become one of these sites that previously attracted a lot of western pilgrims, especially Italians, for whom the journey to Myra was a short hop and a skip across the Mediterranean Sea. Seized by a deep concern for the safety of the bones due to the political chaos of the empire and the presence of Muslim Turks on the borders (and definitely not just by massively cynical opportunism…), in 1087, a group of Italian merchant sailors from the city of Bari in Apulia swiped most of St. Nick’s skeleton from his burial church and happily took him home in their luggage.

The bones arrived in Bari on the 9th of May 10875 and the theft, which the Apulians maintained was a necessary rescue mission, caused a deepening of the rift between the western and eastern Church authorities. The people of the East were scandalised that one of their great patrons could be snatched away from under their noses, whilst the Catholic Pope Urban II was probably weeing himself with smug excitement as he inaugurated the new Church of Saint Nicholas in Bari to house the skeleton and personally placed the bones in a tomb under the altar two years later. Despite the widespread excitement over having a brand new saint on Italian soil, the Apulians were well aware that the manner of his arrival might have raised some eyebrows and were therefore keen to legitimise the entire escapade. If you visit the Basilica di San Nicola in Bari today and turn your eyes to the ceiling, you’ll see an elaborate scene representing a legend that was developed in the years after Nicholas’ arrival in Bari that proposed that he once visited the city in life and predicted that his body would one day be housed there. Which is terribly convenient.

Nicholas’ controversial enshrinement in Bari was largely responsible for the early growth of the saint’s cult in western Europe and, over time, what allowed his veneration to take hold in Germany, where centuries after the medieval age, he was reimagined as Sinterklaas (Santa Claus). Having been a relatively obscure figure before his translation, the new accessibility of his relics to those western europeans using Bari as a launch point to go on crusade meant that sermons featuring his miracles and written accounts of his life multiplied exponentially in the years after the First Crusade. The economic boom and increased prestige that Bari enjoyed as a result of their ‘rescue mission’ soon caught the attention of the Venetians who, after the relative successes of the First Crusade, took advantage of the Eastern Roman Empire’s continuing chaos to sweep up and take back to Venice the few fragments of St. Nicholas that remained in Anatolia.

Relics were spiritual, economic and reputational gold dust. Before long, jigsaw pieces of Nicholas’ body had been stolen from Bari too and were dispersed throughout western Europe.6 Occasionally, relics were given by the Italians to their allies as high-status diplomatic gifts. In 1096, the Duke of Apulia gave the Count of Flanders (who was en-route to the Holy Land) several bones of St. Nicholas which he interred in the Abbey of Watten.

So, St. Nicholas is not only to be found in our hearts at Christmas, he is also to be found in Normandy, Lorraine, Bari, Austria, Belgium, Venice, Bulgaria, Egypt, Greece, Germany, Lebanon, Poland, Palestine, Spain…. you get the idea…

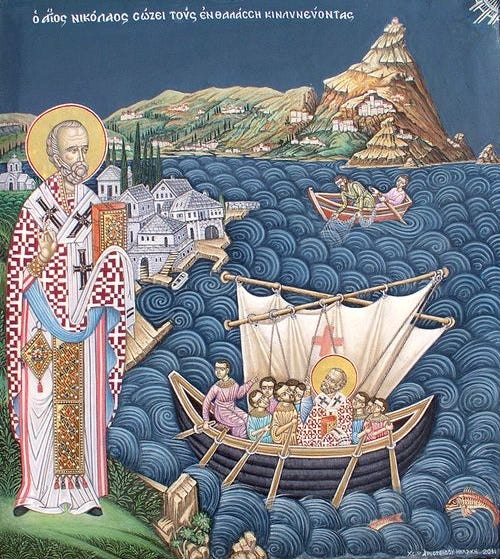

Saint Nicholas is also the patron saint of seafarers

Speaking of Crusaders and thieving Italian merchants - other than being huge St. Nick stans, what do they have in common? Well, it’s that they regularly had to take their life into their own hands by getting on rickety medieval boats.

Partly due to his importance to the Crusaders, who used the port of Bari as their last European supply stop before going on to the Holy Land, and partly due to the island-geography of his homeland of Greece and Turkey, St. Nicholas’ legend developed hundreds of stories of him travelling far and wide by sea.

As a result of this, many in the coastal Italian cities and the Greek islands came to see St. Nicholas as a protector of not only children, but of sailors, fishermen, merchants, and seafaring in general.

One particular legend recorded that as Bishop of Myra, St. Nicholas intercepted a ship at the port that was carrying an export of grain to Alexandria in Egypt. Myra was suffering a great famine and Nicholas begged the sailors to leave some of their shipment behind to help the starving people. Moved by his pleas, the sailors did as he asked and upon reaching Alexandria, they found that miraculously, their cargo hadn’t diminished in size.

To this day, among his many job titles, St. Nicholas is the patron saint of the Greek Navy.

And that’s that! I hope that you’ll look at Santa in a slightly different way now that you know he once saved a bunch of kids from being eaten in a ham sandwich.

Wishing you a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Did you enjoy this article? If so, I have a small favour to ask of you! Please hit the ‘like’ button and leave a comment below on which facts surprised you the most. If you know someone who might find this article interesting - share away! And please subscribe for free with your email so that you never miss a new post. Your likes, comments, subscriptions and shares all help the blog get seen by more eyes which in turn gives me the space, resources and reach to create bigger and better content for you all. Thank you for all your support and Merry Medieval Christmas!

Scholarly estimates for the birth of St. Nicholas in 270 AD place his early life a few years before the decision taken in 286 AD by Emperor Diocletian to split the Roman Empire into two. Each half would eventually have its own emperor. Nicholas’ lifetime straddled this seismic shift in Roman administration.

Not to be confused with the term ‘Aryan’ which was a bogus racial category invented in the 1850s by the aristocratic French writer Arthur de Gobineau, who, through the later works of his followers influenced the radical racist ideology of the Nazis. Bad historians as well as terrible people, the Nazis confused and conflated Gobineau’s bullshit idea of a discrete ethnic group called ‘Aryans’ with the fact that many of the native Germanic medieval tribes at the time of the Council of Nicaea were proponents of an Arianist understanding of Christianity. The Arian Germanic tribes were in fact generally very tolerant towards Nicene Christians and other localised religious minorities, including Jews.

A ‘marriageable’ age in the Eastern Roman Empire was sadly quite young, so these girls were likely what modern people would unquestionably consider to be children.

This story is first recorded in Michael the Archimandrite's Life of Saint Nicholas.

St. Nicholas’ bones arriving in Bari is recorded by numerous chroniclers, including one of the heavyweights of the 11th and 12th centuries, Orderic Vitalis. Incidentally, the 9th of May is still celebrated in some western Christian circles as the day of St. Nicholas’ ‘translation’. For ‘translation’, read ‘movement’ or, if you’re an Orthodox Christian: ‘theft’.

One of the most egregious examples of further relic theft took place in 1090 when a Frenchman from the Duchy of Lorraine stole a finger from the right hand of St. Nick in the basilica in Bari. According to the legend, St. Nicholas had appeared to him in a vision and requested that he do this. I’ll let you decide how valid that is. The Frenchman took the finger home to a town called Port, near Nancy, where a chapel was built especially to house the finger. It became an important pilgrimage centre for followers of Saint Nicholas in northern Europe and the town was eventually renamed Saint Nicolas de Port in his honour.

Hello Clara, I see we are now two weeks off Christmas morning.

And I have been enjoying read quite a few of your posts lately, but now realize I have been quite forgetful and not tagged the like.

I knew a little of St Nicholas' story from the F. Stephen, the priest who prepared my sister and myself for our vows of confirmation in mid 1970's when we lived in Birmingham.

He was a very interesting, kind and spiritual guy. He had been a late convert to Catholicism after becoming C of E priest just after WW2 service as a commando. He had studied at Oxford maybe, but was interested in hagiography and the history of the early christian church.

Our church was the very baroque St Philip Neri Oratory and he was big fan of Cardinal Newman after whom so many university colleges are named.

So your incredible essay certainly made me recall much of this. I hope your PhD thesis is going well.

You and Beth were the next Substack writers that Ifound. The first was Ari Lee (Annyeong Ari).

And certainly a bit of communication due to the events in South Korea over the last 9 - 10 days. when you eventually have time , her posts certainly give an insight into Korea as a place and a society.

So hope you have a joyful and convivial Christmas, and maybe catch up in 25. Cristoffa.