From Stinking Bodies to Hollywood Hotties: The Surprising History of Vampires

Grab a stake and smother me in garlic, it’s a VAMPIRE!

Welcome to the Halloween Substack special! We have a spooky Halloween treat for you and are discussing the history of vampires! This topic extends way beyond the medieval period that we usually explore together, but I hope you enjoy it all the same. This bad boy is a longer read, so be sure to snuggle up with a hot drink by the fire and bed in. As always, if you enjoy this post, please consider liking or sharing the article, leaving a comment, or subscribing for free to join the community.

VAMPIRE: 1. A preternatural being, commonly believed to be a reanimated corpse, that is said to suck the blood of sleeping persons at night. 2. (In Eastern European folklore) a corpse, animated by an undeparted soul or demon, that periodically leaves the grave and disturbs the living, until it is exhumed and impaled or burned. 3. A person who preys ruthlessly upon others; extortionist. 4. A seductive woman who unscrupulously exploits, ruins, or degrades the men she seduces.

There are few things in Western culture that surpass the enduring appeal of the vampire. Vampires dominate Halloween costumes and makeup tutorials, classic horror movie showings at Arthouse cinemas and, for a time in the early 21st century, reigned supreme over Young Adult fiction (Twilight, anyone?)

What exactly makes them so appealing? Is it their stylishness? Their supernatural beauty? The sexual thrill of something that is both dangerous AND alluring? Is it the fact that they’re often very glamorous, presented as wealthy or aristocratic, and thus symbols of a lifestyle that is inaccessible to the masses? It is, of course, all of these things. Because humans are weird.

With this is mind, it might surprise you to discover that Europe’s first ‘vampires’ (as we might recognise them) were bloated, swarthy, and gassy corpses who bled at the mouth and stumbled around villages in eastern Europe wreaking havoc upon their remaining family. In the Middle Ages, unlike the villainous aristocrats of 19th century fiction, vampirism tended to be an almost exclusively peasant problem. Vampires could waltz about during the day if they fancied, begin their afterlives as boneless masses of murderous jelly, and, in Ukrainian folklore, could even have tiny little tails. Basically, the stinking night-crawlers of medieval times were about a million miles away from the twinkling broodiness of Twilight’s Edward Cullen, or the repentant and wildly sexy Vampire Bill and Eric Northman of HBO’s True Blood.

In this article we’re going to deep dive into how and why some of these big cultural changes occurred, hopefully answering some of your questions along the way. Who came up with the idea of bloodsucking demons? Who was the Stinking Vampire of Pentsch? What does Karl Marx have to do with 19th century vampire fiction? And when exactly did vampires get so hot?

Let’s start at the beginning…

The First Vamps: Bloody (Ancient) Women

Where did the idea of ‘vampirism’ actually begin? With patchy evidence it is hard to say for certain, but vampiric mythical creatures are a tale almost as old as time itself. Decoded tablets and shards of excavated pottery from the Middle East suggest that the ancient cultures of the region featured blood-drinking demons, occasionally depicted in artworks as feeding on sleeping human bodies.

Babylonia and Assyria inhabited a shared mythological landscape that featured ‘Lilitu’, a feminised demon or class of spirit that were said to feed on the blood of babies. This likely fed into the legend of a later figure, Lilith, who existed in Hebrew demonology alongside her evil daughters, the Lilu, and shapeshifting female monsters called estries who were said to hunt their victims only by night. Lilith, in Jewish folklore, became a controversial figure of primordial female evil. Said to have been the first wife of Adam, created by God at the same moment, Lilith supposedly fell from grace when she refused to be subservient to him. From then on, in the religious and mythological texts of Abrahamic cultures, Lilith’s whole schtick was seducing, attacking and killing men.

This theme continued into the Greco-Roman period with a smorgasbord of grotesque figures who shared similar characteristics to the earlier Mesopotamian monsters. Empusa, the daughter of a powerful goddess of sorcery - Hecate, is recorded in Greek texts as seducing men while appearing as a radiant young woman and then drinking their blood as they slept. Similarly, the Lamia were depicted as bird- or serpent-like women who fed on children in their beds by moonlight.

What’s the common denominator here? Well… all of these monsters are hazardous women. Though what we know about Mesopotamian culture suggests that women could exercise a reasonable degree of autonomy in public, they were still officially subordinate to men. In ancient Greece and Rome, women’s freedoms were severely limited. It’s interesting to note that the specific behaviours that make these creatures monstrous are the extreme reverse of what ‘good’ women in these societies were expected to do. Instead of nurturing children, these women destroy them; instead of obeying men, these women defy them; instead of creating life, these women drain it away through the blood and, rather than live the life of a chaste wife, these women hunt, tempt, and seduce. In short, disobedient, dangerous women with sexual agency were the stuff of an ancient man’s literal nightmares which is seriously interesting given the turn that vampire culture takes in the 19th century (more on that later).

The Medieval Folkloric Vampire

Though evidence in the ancient world demonstrates that beliefs around bloodsucking demons had existed for centuries previously, the ‘vampire’ as we know it today began to take form primarily in the folkloric beliefs of eastern Europe during the Middle Ages. Slavic ideas about vampirism may well date back much further in the pagan folklore of the region, but it was the introduction of writing and Christianity in the 10th century that made it possible for us to identify them for the first time.1

Slavic peoples overwhelmingly lived in rural areas subject to extreme geographical conditions and it was precisely the precariousness of a life based on subsistence farming in this climate that caused a ‘boom’ in spooky folkloric beliefs. Fundamentally, in swampy wetlands, dark forests and frozen mountains with short growing seasons and long winters, these beliefs served two important functions. Firstly, they allowed people to explain the unexplainable during a time when scientific knowledge was very limited, and, secondly, beliefs that developed attaching monstrous consequences to bad behaviour helped to keep wayward members of the community in line. Vampires emerged, for example, as a response to common ‘wasting’ diseases like tuberculosis, where somebody who had appeared to be healthy would become progressively weaker with no obvious explanation. As an instrument of social order, Church authorities in the village might preach to their congregations that living a life of impious deeds would lead to vampirism after death - the idea being that for communities whose very survival depends on teamwork, that the prospect of harming your peers as an undead monster might put you off a life of crime.

But what were the vampires in these tales actually *like* ?

Well, for a start, there were many ways you could end up as one. Being a magician, being born with enlarged teeth, suffering an untimely or unnatural death, being excommunicated by the Church, having a tail, committing incest, being conceived on certain days of the week, talking to yourself, having an animal jump over your grave, or being buried without proper ritual, could ALL turn you into a bloodsucker. All of these factors in the medieval mind would mark an individual out as being out of God’s favour and a possible danger to society.

In the region of modern Ukraine, tales began to crop up of rotten, red-faced corpses that reemerged from their graves with tails, returning to their villages after death and feeding on the blood of their own families. Meanwhile, in south Slavic stories, a vampire often started its afterlife as an evil shadow, which gradually, gaining strength from the lifeblood of the living, formed a bloody, jelly-like mass, before finally taking the shape of the body that the vampire had in life. Interestingly, at this stage, the vampire (who was usually male) was said to return to his wife and attempt to climb into bed with her, with some legends specifically stating that vampires were capable of fathering children with the living.2 This pattern of vampires being attracted to their former family reoccurred frequently in stories from all over eastern Europe. In Croatia, Slovenia, Czechia, and Slovakia, a type of vampire called pijavica, or ‘leech’, was said to be a person who lived a sinful life as a human, who after death would return to its home and annihilate their relatives. Families in which a person died who had been considered a bit of a knob in life might mash garlic and wine into their threshold and windowpanes to prevent that person from re-entering the house should they indeed rise from the dead. Such vampires could only be destroyed with fire if they were caught awake, or with the Holy rite of exorcism if found in their grave during the day. As a preventative measure, a practice developed all over the region of pinning corpses to their graves with an iron stake to prevent them from popping back up unexpectedly.

Though folkloric in nature, belief in the truth of these legends was such that actual vampire ‘incidents’ were often related in historical documents. Two of the earliest written accounts of vampire activity are found in a Bohemian chronicle of the 14th century: Neplach’s Chronicle (c. 1360). It relates the story of a shepherd called Myslata who died and was buried but didn’t stay put for long. The chronicler explains that the haunting began with Myslata scaring the villagers each night by walking around and talking to them as if he were alive. As things escalated, villagers began to die eight days after he had spoken their names. When the townspeople finally decided to exhume his body to investigate further, the corpse began to scream and fresh blood poured from the wound as he was stabbed through the torso with a stake. Comparably, in 1344, the second case referred to a woman called Levín who returned from the dead and danced on the bodies of those that she had murdered. Here too the proposed solution was staking the body into the grave, though it didn’t do the job in this instance. Only when the villagers burned her corpse with holy wood made from the timbers of the church roof did her murderous spree come to an end.

Despite being vastly more common in eastern Europe, stories of restless and vampiric corpses emerged in medieval England too. Writing in the 12th century in his history of England, chronicler William of Newburgh described various villages as having come under attack from what he called ‘revenants’; a word derived from the Old French word, ‘revenir’ - ‘to return’. Represented as bloated, rotting bodies, these reanimated corpses could supposedly only be destroyed by decapitation or by fire and were often associated with events that shook rural communities, like outbreaks of plague.

Some have theorised that a partial explanation for such accounts is the way that pre-industrial societies attempted to explain any natural processes of death and decomposition that didn’t make sense to them. If a body was exhumed and did not look the way that people expected it to - for example, the body looked plump or ruddy rather than thin and skeletal - people may have misinterpreted these characteristics as signs of continued life. In reality, the gases released during the process of decomposition could have caused the face and torso to swell, even forcing blood from the nose and mouth as the pressure increased. When such bodies suspected of vampirism were staked in a panic, those same gases could force blood and body fluids to explode from the body in such a dramatic fashion that it was concluded that the body had not been truly dead.3

These recorded cases may have been the tip of the iceberg. In the Czech town of Čelákovice an 11th century graveyard was discovered containing 14 bodies (mostly of young adults) that may have been suspected vampires. Each of the bodies had either been decapitated, had their hands and legs tied, or had been pinned to the earth with metal spikes or heavy rocks. In 2017, archaeologists excavating a medieval village in Wharram Percy in Yorkshire found similar human remains that had been decapitated, staked, and burned post-mortem. The possibility that epidemics of unexplained deaths caused a kind of vampire-hysteria in rural areas perfectly illustrates how vampire legends filled the gaps in a rural community’s understanding of disease, death and decay, or represented in a humanoid form the community’s fear of greed and vulnerability to exploitation.

Did you Know? Even early modern accounts of vampirism could be pretty wild. A personal favourite is the story of the Stinking Vampire of Pentsch a.k.a. Johannes Cuntius (his real, and exceedingly appropriate, name). Accounts from 16th century Silesia tell that before joining the ranks of the restless undead, Cuntius, a respected citizen, had been fatally injured by being kicked in the groin by one of his “lusty geldings”. Before he died, he complained of horrifying visions of burning alive and was visited at the exact moment of his death by a black cat. Within a few days of his burial, Cuntius had returned from the grave, newly committed to being an absolute menace to the community. Villagers described encounters with Cuntius as being remarkable for his “most grievous stink” and “an exceedingly cold breath of so intolerable stinking and malignant a scent as is beyond all imagination and expression”. Before long his rap sheet included accusations of making dogs bark at night, turning milk into blood, strangling old men, vomiting fire, bleeding cows dry and chucking goats through the air. Cuntius by name and by nature.

The 18th Century Vampire Controversy

In the minds of the educated upper classes, the arrival of the 1700s and the so-called Age of Enlightenment marked the end of a period of superstition and ignorance. Great energy amongst those who had access to an education was expended exploring ideas on how to make public life better, with advances in medicine, political thought, educational policy and industry all coming thick and fast. That being said, these breakthroughs were largely made in the growing urban centres and had remarkably little impact on the residents of rural communities going mental in the fields at night hunting vampires.

Making its debut appearance in the English language, the word ‘vampyre’ was first used in Britain in 1732 to explain concerning news reports regarding vampire ‘epidemics’ in the Habsburg empire. Out in eastern Europe, where urbanisation lagged behind the countries of the west, folk belief in vampire activity was as widespread as ever. After the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 concluded the Austrian annexation of Serbia and Oltenia, officials sent to document and map the newly acquired territories noted the local practice of exhuming and staking bodies to prevent vampiric attacks. A sudden panic broke out in 1721 in East Prussia after a spate of alleged vampire attacks spurred the locals into mass hysteria, with the reports of these occurrences spreading gradually across Europe between 1725 and 1734.

Cases in Serbia, such as the tale of Petar Blagojevich, were the first cases of vampirism to actually be investigated and recorded by national authorities. Having died at the age of 62, Blagojevich supposedly returned from the dead to beg his son for food. When the son was found dead the following day and neighbours began to die from loss of blood, local villagers lost the plot. Government officials were called in to examine the bodies and wrote case reports that attempted to explain the tales of the local people. As more and more villages reported similar events, the hysteria snowballed into a continent-wide subject of popular interest that is now referred to as the 18th-Century Vampire Controversy.

While the folkloric beliefs of the villagers regarding vampirism may have remained largely unchanged for centuries, the official responses to the vampire ‘problem’ are indicative of a shifting attitude towards the superstitions that had previously plugged the gaps in human knowledge. Where before legend and folklore had been free to run riot, the piles of official case reports, witness interviews and theoretical proposals that accumulated in the face of these unexplained events were evidence of a new desire to explain things using scientific observation. The perfect example of this intellectual trend was a treatise written in 1746 by French scholar and theologian Augustin Calmet called Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants, which weighed up the existing evidence on the existence and nature of bloodsucking demons. Using the reports coming out of the East, Calmet’s thesis proposed various methods of protecting oneself against vampires including burning them, beheading, staking, smearing yourself with their blood or even sucking their gums….

I’ll pass, thanks.

Eventually, the vampire panic reached such a climax that the Austrian Empress, Maria Theresa, sent her personal physician Gerard van Swieten out into the provinces to personally interrogate the claims of the traumatised locals. After a period of investigation, Van Swieten concluded emphatically that vampires did not exist. To put an end to the chaos in rural communities, new laws were passed which prohibited the opening of graves and disturbance of dead bodies which little by little led to a calming of vampire mania and a slow and steady decline in the widespread belief in vampiric entities.

Did You Know? This article is focused on the development of the vampire in European thought and culture, but in reality hundreds of cultures across the world have their own unique versions of the ‘bloodsucking demon’ figure. In Chinese folklore, the ‘jiangshi’, said to be created when a soul cannot leave its body on death, are described as reanimated corpses that hop around absorbing the life essence of their murdered victims. The Tai Dam ethnic minority of Vietnam have the ‘ma cà rồng’, a creature that is able to live among humans but at nighttime uses its enlarged ears to fly into people’s homes and suck the blood of pregnant women. This unusually specific prey is also the preferred meal option of the Malaysian Penanggalan which are described as supernaturally beautiful, demonic women who can detach their head from their bodies and allow it to float freely around rural villages in search of pregnant women’s blood. Horrifyingly, a traditional way of preventing a Penanggalan from invading your home was to decorate doors and windows with spiky plants, so that the loose entrails hanging from the detached head got caught as they tried to enter. Yum.

From Corpses to Counts: Romanticism & Gothic Literature

Once legal reforms, rapid urbanisation, and the intervention of scientific study began to put the folkloric vampire out of the job, vampire culture was gradually translated from the realm of popular belief into the sphere of creative fiction. In the late 1790s a new artistic movement emerged that grew into the space vacated by the wavering scientific energy of the Enlightenment. Partly inspired by the upheaval and the terrors of the French Revolution, a fresh group of artistically-minded intellectuals began to argue that the lofty values of the previous age had simply failed to improve the world in the way that had been promised. Rather than invest their energy into tired political reforms and scientific experimentation, the followers of the new cult of Romanticism focused on the creation of artwork that privileged sublime emotional expression, melodrama, horror, and the dark majesty of the natural world. Rather than seeking to understand the unexplained via scholarship, these artists leant into the mysteries of nature - drawing on folklore, legend, and the occult to ask existential questions about the human condition.

In the background of this artistic pushback against the science nerds, society itself (especially in Britain) was also changing extremely quickly. The beginning of the Industrial Revolution drew the working classes out of the fields and into the cities, where they formed the majority of the workforce needed to sustain factories and infrastructure projects as they popped up in big urban centres. While an age of exciting opportunity for the industrialists, for many European societies these changes led to an unprecedented depth of wealth inequality, poverty, and poor living standards. France’s big fat revolution in the 1790s and the widespread revolutions that took place across Europe in 1848 were the political consequences of a climate in which wealthy, beautiful, aristocratic people at the top of the pyramid were resented more than ever. I’m sure we can’t relate …

In this context, where the upper classes offered an aspirational model to reach towards, but also were feared and hated for their exploitation of the everyman, the word ‘vampire’ began to take on interesting new dimensions. In his entry for the word in the Dictionnaire Philosophique (1764), French intellectual Voltaire notes that the decline in folkloric belief in the existence of real vampires coincided with the rise of “stock-jobbers, brokers, and men of business, who sucked the blood of the people in broad daylight; but they were not dead, though corrupted. These true suckers lived not in cemeteries, but in very agreeable palaces”. Writing in the 1840s and 50s, everyone’s favourite OG communist Karl Marx defined ‘capital’ as "dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks”.4

All of a sudden, vampires are no longer stinky reanimated bodies foaming at the mouth; they are noble, wealthy, and, dare we say it, maybe a little bit sexy? As the conditions of industrial society combined with the Romantic fascination with darkness, monstrosity, and folklore, a new brand of vamp is born.

Enter some famous names to the stage: Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollenstonecraft, the future Mrs Mary Shelley. All members of the Romantic movement, these emo writers had been experimenting with a fresh literary genre which would come to be known as ‘gothic literature’. One evening on holiday together in Europe during a cold, wet and dark summer caused by a huge volcanic eruption, the group decided to have a ghost story writing competition to keep themselves entertained.

Ironically, although this very same evening is the night that Mary Shelley came up with the idea for Frankenstein, a lesser well-known member of the party, Dr John Polidori, Lord Byron’s personal physician, is the focus of our vampire story. That night, Lord Byron came up with the bare bones of a vampire novel inspired by the folk tales of vampirism he’d picked up travelling in Greece and presented it to the group, but ultimately shelved it. John Polidori on the other hand, a self-made man from a humble background, was basically laughed out of the room for his idea of a tale of a skull-headed lady. A fight ensued and Polidori was sent home in disgrace with a chip on his shoulder and a point to prove.

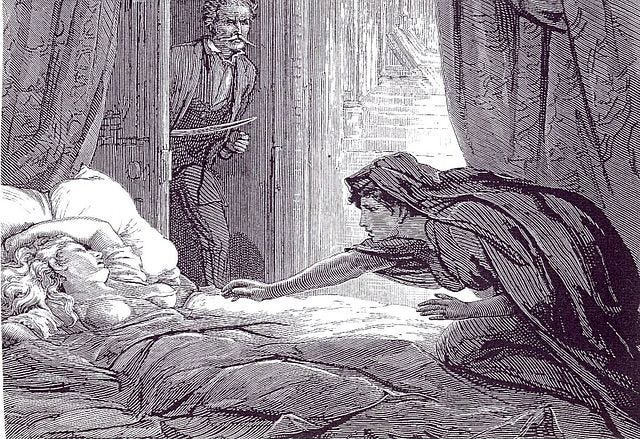

Upon his return home in 1819, using some of the material from Byron’s original idea, Polidori penned The Vampyre, the first proper vampire story published in English. Polidori’s short novel tells the story of Aubrey, a middle class Englishman, and the snobbish, aristocratic, powerful and alluring Lord Ruthven. (Does that dynamic sound familiar? See paragraph above.) Having seen Lord Ruthven killed by bandits early in the story, Aubrey is astounded to meet him again in London at a party and the dark lord eventually marries and kills Aubrey’s sister because … (drumroll) … he’s a bloodsucking vampire! This book, although completely eclipsed in popularity by later texts, really begins to codify some of the elements we expect from a modern vampire. Based as he is so OBVIOUSLY on Lord Byron, Lord Ruthven is hypnotising. His beauty, intelligence and sociopathic ability to charm strangers mean that even after a few girls are mysteriously killed, people just keep on inviting him in to meet their daughters... Aubrey and Ruthven’s relationship perfectly toys with the dynamics of seducer and seduced, predator and prey - with Aubrey increasingly being drawn into the role of an enthralled follower.5

From here on in, a clear vampire formula begins to develop. In 1845 a serialised novel, Varney the Vampire by Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, appeared in the mid-Victorian penny dreadfuls6 before being republished in book form in 1847. Like Lord Ruthven before him, Varney is noble, clever and powerful, and his gruesome exploits take a similarly erotic turn when, mirroring Ruthven and Aubrey’s sister, Varney fixates on, seduces, kills and turns a beautiful young woman called Clara. Varney also marks a watershed moment in the history of vampire culture by leaning into the idea of the repentant vampire. Laying the groundwork for the vegetarian Cullen family in the Twilight Saga, Varney is a brooding protagonist, disgusted by his own compulsion to kill, and eventually, in a dramatic moment of self-destruction, ends his own afterlife by throwing himself into the crater of Mount Vesuvius.

Drawing on the female monstrosities of the classical world, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) then gave English literature our first bestselling vampiress and takes the eroticism of previous vampire stories to a new level while building on some of the common features of Varney and Ruthven. Described as supernaturally beautiful, coquettish and intelligent, Le Fanu’s aristocratic Carmilla is a somewhat sympathetic character, frustrated by her own inability to successfully resist her murderous urges. Playing on the established pattern of portraying abusive and codependent vampire/human relationships, Carmilla scandalised the public when it was published for its homoerotic scenes. Far from a charming LGBT+ rom-com moment, Carmilla’s lesbian proclivities reflected a societal fear of untethered or ‘deviant’ sexuality which further entrenched the conceptualisation of the vampire as an attractive sexual, as well as literal, predator.

The Invention of Dracula

Simply the most recognisable, reinventable and memorable vampire ever created, Bram Stoker’s 1897 smash hit Dracula is often credited with fixing the characteristics of vampirism in the modern mind. Without spoiling the plot too much (you absolutely must read it yourself) the story begins with Jonathan Harker, a middle class Englishman, travelling to Transylvania to broker a lucrative real estate deal. This arduous journey brings him to the castle of one mysterious Count Dracula. Having rudely ignored the warnings of the local villagers about the weird stuff that happens in the castle, Jonathan is attacked by sexy vampire women and trapped. Back in England, Harker’s sister, Mina, and her friend Lucy are in Whitby. A ghostly looking ship washes up in Whitby with no crew and a dead captain and a large black dog jumps ashore which is Count Dracula in a bestial form. Lucy begins to sleepwalk and to experience a wasting illness which a doctor, Dr Van Helsing, recognises as the symptoms of a vampire attack. Despite everyone’s best efforts, Lucy becomes a vampire and Mina becomes the new focus of Dracula’s attention. Jonathan finally escapes the castle and then along with Van Helsing and Lucy’s grieving suitors, must try and destroy the Prince of Darkness before it’s too late.

In many ways Dracula wasn’t particularly original. The parasitic count, emerging from his castle at night to feed on the local peasantry, surrounded in his home by dusty piles of money, was a continuation of the aristocrat-as-exploiter trope developed earlier in the century. His ability to shape-shift into animals and his power to control the weather draw clearly on the traditional vampires of eastern Europe, where Dracula himself, as a Transylvanian, was from in the book. Stoker also borrowed a huge amount from Le Fanu, his personal friend, and indeed a highly sexualised scene in which Lucy’s suitors give her a blood transfusion in an attempt to save her profoundly echoes the eroticism of the earlier Carmilla.

So what exactly made Stoker’s book so impactful?

Like most successful literature, TV, or film that deals with the supernatural, Dracula appealed to the audience of its time by manifesting all their anxieties in their most monstrous form. Building on the themes of Varney and Carmilla, Stoker’s portrayal of vampirism as an illness tangled up with blood, sex and demonic possession fabulously dramatised Victorian disease outbreaks of tuberculosis, syphilis and cholera. Dracula also reflects the alarming pace of change in British society at the turn of the 19th/20th century. For contemporary readers, the novel would have felt strikingly up to date - the work is full of slang and the main characters are obsessed with the use of innovative technologies like audiographs, shorthand, and Harker’s Kodak camera.

Did you know? Dracula is one of the world’s most adapted characters. It has been adapted more than 700 times in film, television, video games, books and animation. The first adaptation of Dracula was by Bram Stoker himself who wrote a script for a theatre version to establish his copyright over any such material. It premiered at the Lyceum Theatre on 18 May 1897, shortly before the novel’s release.

Clashes between urban and rural culture and a fear that the world might have been changing a little bit too fast are encapsulated in the protagonists’ struggle against an ancient evil. For all their understanding of modern technology, it is only through an understanding of traditional folkloric customs that the group are able to formulate strategies to defeat the Count. The figure of Van Helsing represents an elite combination of a modern man of science with a dedicated student of the ‘old ways’ of a rural existence. Jonathan’s early rejection of what he sees as the antiquated belief systems of the villagers is precisely what gets him into trouble in the first place and it is only by finally embracing those same beliefs that he is able to survive. This fusion of modern science and superstition is now a mainstay of vampire fiction. Despite modern society’s capacity to introduce the synthetic blood product ‘TruBlood’ to keep the veggie vampires alive in the TV drama of the same name, the vamps still inexplicably have to be invited to cross the thresholds of the human characters in the drama, remaining subject to unexplained occult forces.

So, there you have it. A whistle-stop tour through thousands of years of making up things that go bump in the night. In a book titled Our Vampires, Ourselves, Nina Auerbach argues that each age and society embraces the vampire it “needs” and gets the vampire it “deserves”. Whether its disgusting corpses that encourage you to behave and go to Church like a good medieval peasant, or a vicious moneyed aristocrat that warns you to be wary of your shitty factory boss, vampires have been a million different things to different people across the centuries. Perhaps in 2024 the next bestselling work of vampire fiction will be an undead Gwyneth Paltrow selling cursed vagina eggs… Who knows?

Further Reading

The below links are affiliate links. If you choose to purchase a product using the links provided here, I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. By using these links you are supporting me and my work, allowing me to continue to get creative and keep posting fresh content for you all. For this, I cannot thank you enough!

Our Vampires, Ourselves - Nina Auerbach (1997)

Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality - Paul Barber (1988)

The Vampyre - John Polidori (1819)

Varney the Vampire - Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Press (1847)

Carmilla - Sheridan Le Fanu (1872)

Dracula - Bram Stoker (1897)

The Slavic peoples of central and eastern Europe didn’t get around to writing things down until Christianisation, which occurred around the year 988 in a principality known at the time as Kievan Rus (which is in modern day Ukraine). Up until this point, the state had stubbornly held on to its pagan belief system, but political opportunity changed all that. Recognising the possible perks of affiliation with a larger religious bloc, Grand Prince Vladimir converted the kingdom to Christianity. Apparently he was equally willing to convert to Islam until somebody broke the news to him that this would mean giving up booze…. Jesus it is I guess.

Interestingly, in some of these stories such hybrid children, with a vampire parent, grew up to have the special ability to see and to kill other vampires. The first professional vampire hunters, if you will.

Barber, Paul (1988). Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality. New York: Yale University Press. pp. 1-4

A great discussion of the vampire metaphor in Marx's writings can be found in Policante, A. (2010). "Vampires of Capital: Gothic Reflections between horror and hope". Archived 6 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

Polidori’s life is actually quite a tragic one. When The Vampyre was published in 1819, an unscrupulous publisher called Henry Colburn published the book under Byron’s name, hoping to capitalise on Byron’s huge celebrity status. Byron himself was furious, disgusted that a book he felt was shoddy work was being associated with him and it led to a huge irreparable fall out between him and Polidori. Constant speculation over Polidori’s sexuality and his exact relationship to Byron also coloured people’s interpretation of the frisson between Aubrey and Ruthven in the text. Sadly, Polidori died aged 25 in a suspected suicide, plagued by gambling debts, depression, and disgrace.

Penny dreadfuls were pamphlets circulating popular literature, so named because of their accessible prices and gruesome or sensational contents.