Beans, Boars & Boy-Bishops: A Merry Medieval Christmas!

8 facts about Christmas in the Middle Ages you might be surprised to know...

Welcome to the first of my festive December Substack specials! Today we’ll be discussing the Medieval celebration of Christmas and the ways in which it is like and unlike our own experiences of the holidays. As always, if you enjoy this post, please consider liking or sharing the article, leaving a comment, or subscribing for free to join the community. It’s very much appreciated.

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! Festive preparations in homes across the globe are in full swing. Those readying themselves to host the family meal are freaking out about the state of the house, people everywhere are psyching themselves up for Christmas Day with their in-laws for the first time, every other advert on the TV hits you in the feels like an emotional freight train, and children worldwide happily mash potatoes, chocolate and minted peas into their parents’ furniture without a care in the world.

In many ways, the celebrations we are currently preparing to enjoy with our families would be super recognisable to people in the Middle Ages. This description of the merriment at the Arthurian court of Camelot, drawn from the late 14th century romance, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, speaks to exactly the kind of convivial festivities that still resonate today:

“It was Christmas at Camelot, and there was the king with his leading lords and all his best soldiers, the famous company of the whole Round Table – celebrating in style: not a care in the world. Again and again strong men tussled, and the noble knights jousted with vigour till they rode to the court to start dancing. Celebrations continued the whole fortnight with all the feasting and pleasure that people could think of. It was fine to hear such a glorious commotion: lively uproar all day and dancing at night… With the change of the calendar on New Year’s Day the courses were doubled for the top table. When the king and the knights arrived in the hall and Mass was over in the echoing chapel, the singing continued from priests and the rest, and ‘Noel!’ was called out over and over. Then out they ran to bring in the presents, and, shouting greetings, the handed them round, excitedly arguing which were the best… Delicacies were brought of the rarest foods in endless abundance, on plates of such number it was hard to find room in front of the diners to set down the silver that held all these dishes there on the cloth. No one stinted them as they all helped themselves. Twelve dishes to each couple, good beer and gleaming wine. I’ll give you no more details about this rich feast; you’ll have got the idea, there was no shortage.”

Though the above scene is a fictional account of celebrations in a fictional royal court, the opulent celebrations described are fairly representative of how winter festivals were enjoyed by the poem’s aristocratic audience. While we know comparatively less about how ordinary peasants celebrated the Christmas period (simply because it was less likely to be recorded), there is enough evidence to suggest that it involved as much feasting, dancing and boozing as your work Christmas party probably did last week.

But how was a medieval Christmas different to what we know today? What else did medieval people do at Christmas? What kind of presents did they give? Given that Monopoly hadn’t been invented, what kind of games did medieval families furiously fall out over? And what in God’s name is a ‘King of the Bean’?

Here are 8 facts about a merry medieval Christmas that you might like to know…

1. Christmas in the Middle Ages was an absolute marathon

Have you ever rushed to pull down your Christmas lights on the 6th of January, panicking all of a sudden that a failure to do so might give you bad luck for the year ahead? For most of us, the Twelfth Night of Christmas, or Epiphany, is the formal end of just under two weeks of eating chocolate for breakfast and being completely unaware of what day it is. For most people, 12 days of family, hangovers and chaos is quite enough.

Well, speak to medieval person about being exhausted after your paltry twelve days of Christmas and they’d think that your stamina was sorely lacking. Medieval people were in Christmas mode for the long-haul.

The medieval Christmas season was a slow-burn situation with various, distinct stages and a smattering of significant religious celebrations across December, January and February. This dense period of Catholic liturgical milestones likely reflects the fact that the early Church set the dates of major Christian festivals around the time of existing pagan celebrations. The reasons for this were probably two-fold. Firstly, it was a useful tool of conversion. Telling people they could no longer enjoy the raucous silliness of the Roman Saturnalia or the germanic Yule festival probably wouldn’t have gone down very well unless the Christian clergy were able to point toward a suitably joyful alternative. By subsuming pagan rituals into Christianity and selling it back to the population with a healthy helping of Jesus Christ, early Christians were able to make their fledgling religion seem a lot more attractive to potential converts. Secondly; shorter, darker and colder days during the European winter months made the season ripe for the organisation of festivals that gave people a much needed mid-winter boost.

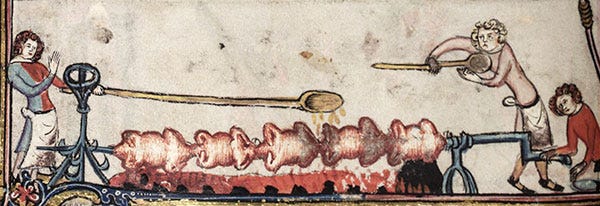

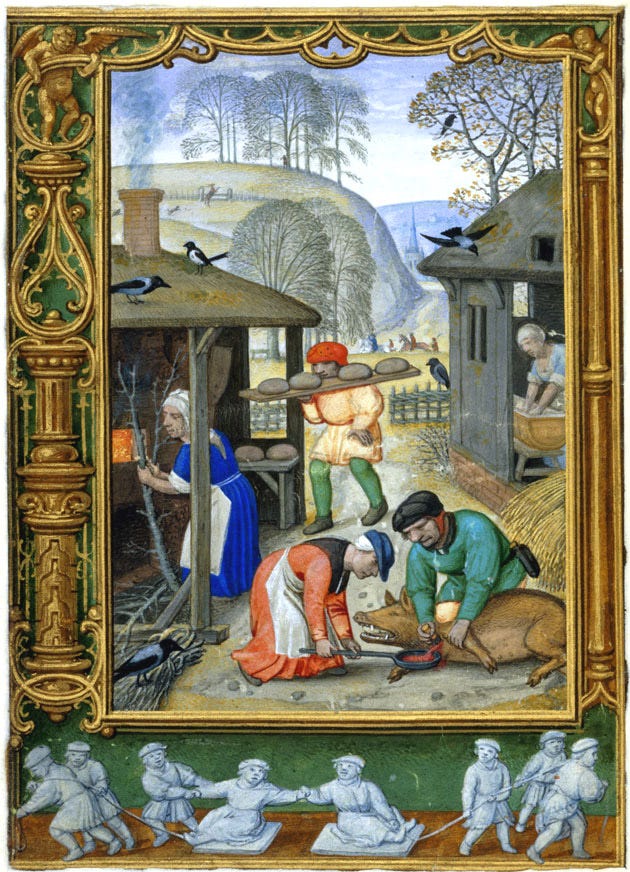

Preparations for Christmas began with the movable feast of Advent, which always comprised the period of the four Sundays prior to Christmas Day and thus could vary considerably in length. While for us Advent is a time of excitement and a daily dose of chocolate from the calendar, Advent for medieval people was an altogether more sombre period of fasting, prayer, and ideally no shagging. Think of it as the Christmas version of what Lent is to Easter. Important preparations for winter took place during Advent, like the slaughter of animals and the preservation of meat for the colder months ahead.

Despite the generally more reflective mood of the Advent season, it was punctuated with religious feast days that gave medieval people the chance to let their hair down such as St. Nicholas’ Day on the 6th of December (stay tuned for a post later this week on that guy) and the Feast of the Immaculate Conception on the 8th.

Christmas ‘proper’ actually began on Christmas Day1 itself and included the twelve days between the birth of Christ and Epiphany,2 the festival on the 6th of January that celebrates the arrival of the three kings to Bethlehem. The twelve days of Christmas were frankly stuffed full of religious significance with St. Stephen’s Day on the 26th, the Feast of St. John the Evangelist on the 27th, the Feast of the Holy Innocents on the 28th and the Feast of the Circumcision celebrated on the 1st of January.

Seasonal merriment (especially in the noble households that could afford it) dragged on all the way until a festival popularly known as Candlemas on the 2nd of February. Candlemas marked the date of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary and was accompanied by huge processions of parishioners marching candles into a special mass as an offering to the Church. These candles were then blessed and often placed into the homes of the sick or the needy to bring them good luck.

Three months of Christmas? I’m tired just thinking about it.

2. Gift giving is an ancient part of winter festivals, going back even further than the Middle Ages…

Whether you love it or loathe it, exchanging gifts at Christmas time is one of the cornerstones of our winter celebrations. Gift giving has in fact formed an important part of winter festivals since long before the Middle Ages, with notable precedents in classical Roman culture. Saturnalia was a Roman festival that took place between the 17th and 23rd of December, honouring Saturn, the god of time, renewal, abundance, wealth, and liberation.3 This period of feasting and revelry also included the giving of gifts, often with a particular emphasis on giving wax dolls and other small tokens to children. Kalends, celebrated by Romans on January 1st and intended to recognise new administrative appointments, involved gift giving to wish people luck for the year ahead with presents such as honey, coins and figs.

Though gifts were also exchanged throughout the Christmas period in the Middle Ages, New Year’s Day was far more popular than Christmas Day itself when it came to this. Likely partially influenced by the tradition of Kalends, New Year’s also coincided with the rowdy celebrations of the Feast of the Circumcision 8 days after Christmas. Much like the pagans who celebrated Kalends centuries before, medieval day-to-day life revolved principally around agriculture, seasons, and the passage of time, meaning that festivals marking such occasions of renewal and rebirth were a big deal to the community.

So, what might you expect to receive during a medieval Christmas season? If you were a lucky peasant or household servant, your gracious lord and lady might give you a small gift of money to reward you for your loyal service. Wealthier people might opt for gifts that reflected the religious significance of the season by gifting their friends and family devotional images, prayer beads, or even ornately illuminated prayer books.

For most people, gifts of food were the likeliest option. Common people who were invited to participate in the festive celebrations of their noble landlords would often bring a sample of their finest produce as a sign of gratitude and as a recognition of their humble status. Things like vegetables, beer, or fat chickens went down well. Wealthy religious communities could be particularly generous at Christmas, with the monks of the Christ Church at Canterbury once gifting the Archbishop a whopping 785 chickens as a pressie. Recognising that he would be unable to eat so many chicken nuggets alone, the Archbishop distributed the chickens amongst the monastic servants and the needy & sick at local hospitals.

So, as you’re opening your packet of extra durable bin-bags that your weird uncle wrapped up for you this Christmas, just take heart from the fact that the feeling of festive confusion and disappointment you’re feeling over an underwhelming gift is one probably shared by thousands of Roman and medieval people before you as they were handed figs or a bag of carrots.

3. Christmas just isn’t as ‘pagan’ as some people insist

As we’ve already touched upon, it is entirely possible that Christian feast days were deliberately situated to eclipse pre-existing mid-winter pagan festivities, but to suggest that these early medieval pagan festivals somehow morphed into Christmas is a wildly inaccurate oversimplification.

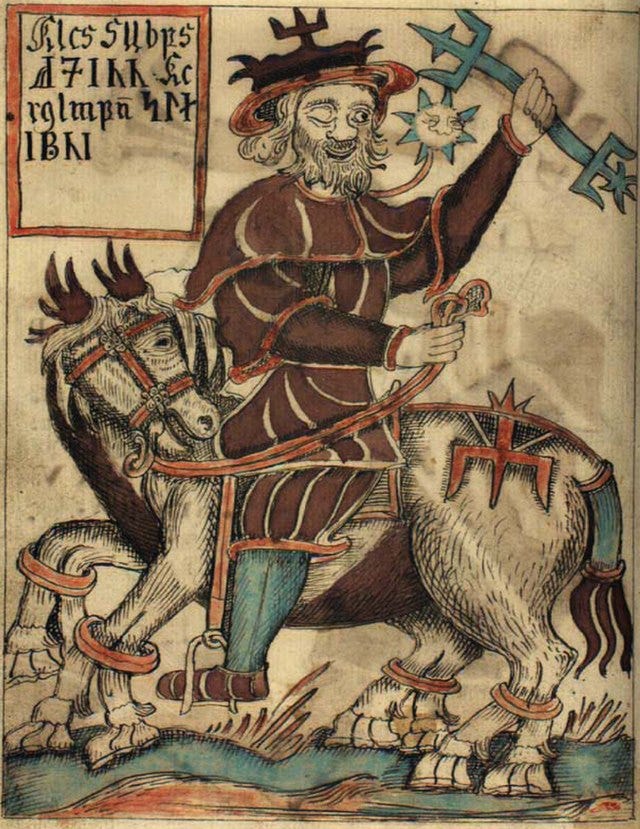

The winter Yule festival, celebrated in pre-Christian times by germanic tribes from Anglo-Saxon England to Scandinavia and the Baltic States, is one that some people have argued exerted a profound influence on the celebration of Christmas. Yule is a word that appeared early in the history of the germanic peoples. In a Gothic calendar that dates to the 5th or 6th century, it appears in the name of the month ‘fruma jiuleis’ (written in Gothic as 𐌾𐌹𐌿𐌻𐌴𐌹𐍃) and in Old Norse sagas as ‘jól’ or ‘jul’. The word also appears in Old English (the language of the Anglo-Saxons) as ‘ġēol’, where the great Northumbrian historian Bede used it in the 8th century to describe a month in the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon calendar that corresponded roughly to December and January. It was little more than the parallel timings of Yule and Christmas that led to the eventual appearance of the compound noun ‘Yuletide’ ('Yule-time') which first cropped up to describe the festive period in general around 1475 and cemented this idea that Yule had somehow acted as a precursor to Christmas.

In reality, medieval Yule had very different emphases to any Christian festivals. It likely developed out of Stone and Bronze Age rituals of mid-winter sacrifices and ancestor veneration. An association with death and the supernatural is attested in the Old Norse sagas where it is connected with the Wild Hunt, a ghostly procession of warriors in the night sky led by Oðin, bearing the name Jólnir (‘the Yule One’), and creepy stories of the undead draugr who hunted the living at night.

A description of Yule in the Saga of Haakon the Good, which recounts the Christianisation of Norway by King Haakon I, communicates this distinctly un-Christmassy vibe:

“It was ancient custom that when sacrifice was to be made, all farmers were to come to the heathen temple and bring along with them the food they needed while the feast lasted. At this feast all were to take part of the drinking of ale. Also all kinds of livestock were killed in connection with it, horses also; and all the blood from them was called hlaut [sacrificial blood], and hlautbolli, the vessel holding the blood; and hlautteinar, the sacrificial twigs [aspergills]. These were fashioned like sprinklers, and with them were to be smeared all over with blood the pedestals of the idols and also the walls of the temple within and without; and likewise the men present were to be sprinkled with blood. But the meat of the animals was to be boiled and served as food at the banquet. Fires were to be lighted in the middle of the temple floor, and kettles hung over the fires. The sacrificial beaker was to be borne around the fire, and he who made the feast and was chieftain, was to bless the beaker as well as all the sacrificial meat.”4

However, you’ll be pleased to know that the pagan connections aren’t all bogus. There is evidence that holly, ivy and mistletoe, all modern Christmas staples, were woven into elaborate decorations for Yule celebrations too, probably because they were some of only a few attractive evergreen plants that looked good in the depth of the winter. The attraction that the pagan revellers felt towards these plants as symbols of endurance, rebirth and fertility was appropriated by later Christians who connected the survival of holly and ivy through the winter with the eternal life of Jesus Christ and the white berries of the mistletoe with the heavenly purity of the Virgin Mary.5

4. Children had a special role to play through parts of the medieval Christmas season

I think most can agree that Christmas is particularly exciting for children (those lucky little scamps who aren’t expected to buy gifts, frantically tidy up ahead of festive gatherings, and cook a massive turkey under extraordinary pressure). For medieval kids, there were certain days throughout the Christmas period on which they really got to play a starring role.

The first of these celebrations took place during Advent and was the Feast of St. Nicholas on the 6th of December. Though I’m not going to go too deep into this now (watch this space for an imminent post on St. Nicholas), St. Nick had a reputation as the patron saint of children, so kids were often given a little extra attention on his feast day.

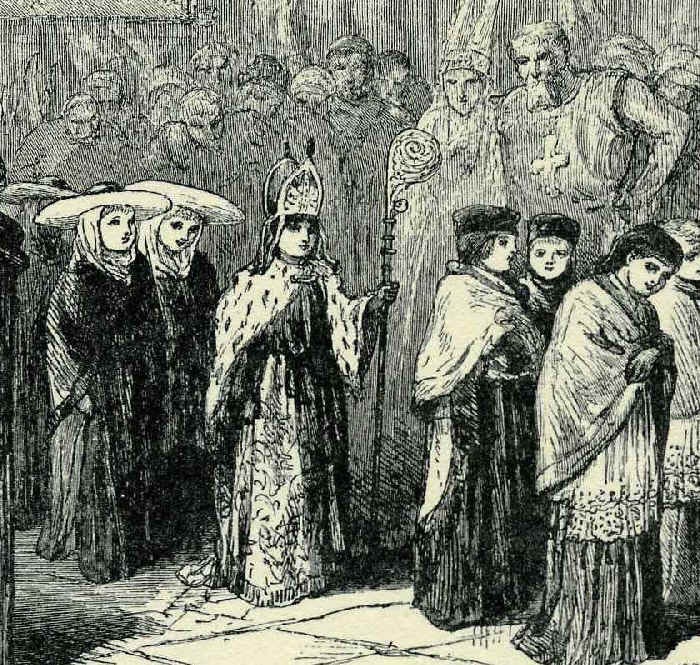

The second of these mega child-friendly festivals (weirdly) was the Feast of the Holy Innocents (or Childermas) on 28th of December which commemorated King Herod's failed attempt to murder the infant Jesus by ordering the immediate execution of all the children in Bethlehem under two years old. Perhaps oddly to us, considering the gruesome solemnity of the anniversary, this date was often celebrated by indulging in humorous role-reversals. Sometimes elected ahead of time on St. Nick’s day, medieval religious communities would nominate a ‘boy-bishop’ to take over the traditional role of the higher clergy until Holy Innocents’ Day.

The boy-bishop would deliver sermons, lead torchlit processions, and temporarily oversee the affairs of the diocese while the clergymen occupied the traditional place of the children in the cathedral choir. I personally can’t imagine I’d have been equipped to conduct the administration of an ecclesiastical institution as an eight year old, but I can see how a child’s attempt to do so might have been an amusing spectacle for all involved.

Sadly, party-pooper-in-chief, King Henry VIII, abolished the practice in the 1540s, finding it all a bit too Catholic, but it was temporarily revived by his daughter, the Catholic Queen Mary I. A boy-bishop could expect to be lavished with gifts of clothing and money for their troubles. This was a sweet, sweet gig if you could get it.

5. Role reversals and drunken mischief were a crucial part of medieval Christmas celebrations

Role reversals like the boy-bishops were a key part of medieval Christmas partying. Such conventions that disrupted the normal social order might well have been the inheritance of Saturnalia and other pagan precedents, though it is equally as likely that topsy turvy revelry where the powerful were temporarily made humble simply had a mass and enduring human appeal.6

One of the most distinctive role reversal traditions of the medieval period was the annual election of a ‘Lord of Misrule’. Often a peasant, a subdeacon, or a similarly humble member of the community, the Lord of Misrule was elected by lot during Christmas to preside over the Feast of the Circumcision in early January. This particular feast was such a raucous one, known for its extreme drunkenness and outlandish behaviour, that it earned the nickname the ‘Feast of Fools’. Versions of this tradition differed by region with Scottish people electing ‘Abbots of Unreason’ and French medieval gatherings opting for a ‘Prince des Sots’ (‘Prince of Fools’).

Court records from the Tudor period mention it a number of times which suggests that the aristocrats liked to get rowdy in this way as much as the common folk did. John Stow, an early modern author, writing in 1603 in his Survey of London, described instances where the Lord of Misrule was elected for literally months, staying in his post from Halloween to Candlemas, taking charge of all kinds of fun:

“In the feaste of Christmas, there was in the kinges house, wheresoever hee was lodged, a Lord of Misrule, or Maister of merry disports, and the like had yee in the house of every noble man, of honor, or good worshippe, were he spirituall or temporall. Amongst the which the Mayor of London, and eyther of the shiriffes had their severall Lordes of Misrule, ever contending without quarrell or offence, who should make the rarest pastimes to delight the Beholders. These Lordes beginning their rule on Alhollon Eve [Halloween], continued the same till the morrow after the Feast of the Purification, commonlie called Candlemas day: In all which space there were fine and subtle disguisinges, Maskes and Mummeries, with playing at Cardes for Counters, Nayles and pointes in every house, more for pastimes then for gaine.”

Aside from allowing the Lords of Misrule to organise drinking, dancing, card games and fancy dress, the Feast of Fools encouraged everyone else to also lean into the themes of silliness and reversal. Accounts exist of clergy wearing their clothes inside out, animals being allowed to attend masses in Church, and groups of singers wearing animal masks roaming the streets making donkey sounds.

I’d like to say that we’ve all been there, but I don't think I’ve ever been THAT drunk…

6. Some aspects of medieval Christmas entertainment, however, might be more familiar to you…

Some of the entertainment during the winter season of religious festivities was a little more civilised, including activities involving the whole community that we still participate in today in some form, like nativity plays.

Almost completely uniquely in regards to dating the emergence of Christmas traditions, we can give with relative certainty the date of the first ever live nativity scene performed in Europe. Thanks to a written account of 1230 from an Italian friar called Thomas of Celano, we know that St. Francis of Assisi (of whom Thomas was a disciple) organised the first nativity exactly 800 years ago, in 1223, in a cave in a town called Greccio.7

According to Thomas, while visiting Greccio, Francis felt inspired and ordered a pious local called John to help him organise a performance in honour of Christ's birth, telling him:

"If you wish to celebrate the approaching feast of the Lord at Greccio, hurry and do what I tell you. I want to do something that will recall the memory of that child who was born in Bethlehem, to see with bodily eyes the inconveniences of his infancy, how he lay in the manger, and how the ox and ass stood by.”

Gathering together people and animals to recreate the cast of principle characters, Francis’ nativity scene was a hit and gradually inspired copycat events all over Europe.

Performance and ceremony was a vital part of medieval religion, allowing an illiterate audience who did not speak a word of Latin to access the stories of Scripture in a dramatic, moving, and involving way. Mystery plays that reenacted other biblical stories dominated the performance landscape of the medieval Christmas season, with touring companies of monks retelling Christmassy episodes such as the Massacre of the Innocents, the arrival of the magi, and the angels calling to the shepherds in the fields. When the medieval Church authorities decided that it would perhaps be best if monks stuck to praying rather than getting involved in loud, drunken and rowdy public festivals, guilds of craftsmen took up the practice of performing Christmas plays in their place.

The plays of these guildsmen-actors often overlapped with a parallel tradition of ‘mumming’. Mummers were masked troupes of actors, dancers and singers in vibrant costumes who, accompanied by musicians, would wander from house to house demanding tokens of food and booze in return for their entertainment. Borderline breaking into someone’s home and insisting on being paid off in beer might seem a little terrifying to a modern audience, but the patterns of audience participation are not a million miles away from door to door carol singing or the self-conscious slapstick of the modern Pantomime. We know that mumming was immensely popular because there were several attempts by the Church and royal authorities to ban the practice entirely. Classic killjoys.

7. Family table games and festive humour really haven’t changed all that much

Are you dreading the inevitable familial civil war that erupts from dodgy Monopoly dealings? Or are your family card game people? Either way, you probably have a lot in common with someone getting ready to celebrate Christmas in the Middle Ages. Games of cards and dice which often included quite a bit of gambling (much to the Church’s utter disgust) were very common, and familiar board games such as checkers and chess (an exotic import from the Sanskrit and Arabic east) also showed up a lot.

One very popular traditional game was the ‘King of the Bean’ or the ‘Queen of the Pea’. A bean would be baked into a loaf of bread or a cake which was then shared around the feasting hall. One by one the guests would be nominated (often by a child) to tuck into their slice of the loaf and the person whose section had the bean in would be named the King or Queen of the feast. At this point, the game becomes a little bit like ‘Simon Says’, with the rest of the company expected to mimic the behaviours of the King or Queen until the end of the meal. King of the Bean was normally played on Twelfth Night and is another of the medieval feasting practices that some have argued was influenced by Saturnalia.

Though the medieval age can seem very distant to us now, it is worth reminding ourselves that medieval people… were also people… and enjoyed much of the same kind of juvenile silliness that we do. Even kings.

One of my favourite examples of this is a 12th century description of King Henry II of England’s favourite Christmas entertainment. Though Henry was a notoriously angry, cold and grim character, each year he paid his favourite jester called Roland an extra sum of money to perform his special Christmas show. Henry came to enjoy Roland’s spectacular performances so much that he even gave him a house with land in Suffolk as a reward for his service. What was this act, you may ask?

Well, Roland’s nickname at court was literally ‘Roland the Farter’ and his festive spectacular included what one account describes as a sequence of “a hop, a whistle, and a fart”. In case you were wondering, the medieval Latin word used for ‘fart’ is the magnificent ‘bumbulum’. So, next time you feel like you’re about to terrorise your family with gas after eating too many sprouts, just remind yourself that your noble flatulence is something that a king of England once paid a guy to do professionally.

8. Christmas time was a time to enjoy food in a big way

Aside from Church, medieval Christmas revolved around two things only: drinking and eating. After up to a month of fasting and restriction during the relatively mild month of the December Advent,8 Christmas was a time when medieval people really went all out and celebrated the enjoyment of food before the harsher winter months.

Now, a turkey for Christmas dinner was out of the question. Turkeys are native to the New World and thus did not make an appearance in European cooking until after 1492. The same is true of the humble potato. Imagine. Christmas dinner without roasties.

This being said, roasted meat still formed the main element of Christmas feasting for the medieval wealthy. Dishes included goose, chicken, pork, beef, game, and even fish, which would be flavoured with a surprising number of fruits and spices. A medieval recipe for a pork dish called ‘cormarye’ instructed medieval master-chefs to:

“Take coriander, ground caraway seeds, powdered pepper and garlic, in red wine; mix all this together and salt it. Take the raw pork loins and flay off the skin, and prick it well with a knife, and lay it in the sauce. Roast it when you will, and keep the pork that falls away in the roast and boil it in a posset with light broth, and serve it with the roast.”

Interestingly, the crusades had quite the influence on medieval Christmas cookery. Knights who travelled to the Middle East were exposed to unfamiliar flavours that had arrived along the Silk Roads from the Far East. Having developed a taste for it and returned home to Northern Europe, the decades after the initial crusades saw a boom in the importation of foreign spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon, ginger and even galangal.

Meat-wise, royals and high-ranking nobles were fond of a roasted boar’s head as a centrepiece. Boar-hunting was an exclusively rich-person hobby in the Middle Ages as it was difficult, dangerous and expensive. As a prestigious and exclusive sport, displaying the spoils of your hunt at feasts was a way for the members of the warrior class to do a classic humble brag. Similarly, medieval royalty was known to enjoy an exotic-looking roasted peacock, which would be skinned (keeping the feathers intact), roasted, and then put back into the feathers to display as an impressive table decoration.

We know that royalty went big for Christmas. In the year 1213, King John, a contender for medieval England’s most dislikable character, ordered a whopping 400 heads of pork, 3000 fowls, 15,000 herrings, 10,000 eels, 100 lbs of almonds, 2 lbs of spices and 66 lbs of pepper imported from India. That is one hell of a big shop.

Minor nobility didn’t go quite as hard. The household accounts of Sir Hamon le Strange of Hunstanton in Norfolk detailed his expenditure for the Christmas of 1347, buying in enough food to serve Sir Hamon and his wife, Sir John de Camoys, Lady de Camoys and her maids, and Hamon’s servants: “Richard the chaplain, the butler, the cook, with the groom, two boys, and one lad”. The accounts read:

“For bread bought for the kitchen by John the cook, 1/2d. For 2 gallons of wine bought at Heacham by the lord, 12d. In store, 1 porker for the larder, price 4s; 1 small pig, price 6d; 1 swan from the lord John Camoys, price… 2 hens of rent. And received from Gressenhall 6 rabbits, and 2 rabbits from John of Somerton as a gift. Whereof consumed 5 rabbits and one ham.” [d = pence, s = shillings]

What did regular people eat? Probably less meat for a start, as this was very expensive. But that didn’t mean that peasants didn’t also do something special for the occasion. Some contemporary accounts describe commoners cooking up a stew that would be topped with a dough lid sculpted into the shape of birds and animals. Fancy!

So that’s it! That’s a medieval Christmas. However you choose to celebrate yours next week, I’m wishing you the very happiest one possible. Gaudete in Nativitate Christi (Rejoice on Christ’s birthday!)

Did you enjoy this article? If so, I have a small favour to ask of you! Please hit the ‘like’ button and leave a comment below on which facts surprised you the most. If you know someone who might find this article interesting - share away! And please subscribe for free with your email so that you never miss a new post. Your likes, comments, subscriptions and shares all help the blog get seen by more eyes which in turn gives me the space, resources and reach to create bigger and better content for you all. Thank you for all your support and Merry Medieval Christmas!

The date of Christmas Day historically speaking is completely arbitrary. A heated conversation surrounding the date of events in Christ’s life was ongoing in Middle Ages and was perpetually inconclusive. Church Father Sextus Julius Africanus, writing in the second and third centuries, declared that Jesus Christ was conceived on March 25th which he argued was the anniversary of God creating the Earth, implying a birth date on the 25th December. The theologians of the Middle Ages eventually felt this date was as good as any and totally ran with it.

Historical uncertainty around the exact birth date of Jesus is also responsible for the (extremely boring in my opinion - just use what makes you happy) BC/AD or BCE/CE debate. Although medieval scholars placed the year of JC’s birth as the year zero, most modern scholars would now argue that the historical Jesus must have actually been born somewhere between 4 and 6 BC or ... BCE. This is because the big bad of the Bible’s nativity story, King Herod, murderer of children, was already dead by the year 0, meaning that he could not have persecuted babies in search of the newborn messiah that year.

Epiphany is still a more significant date than Christmas Day itself in many parts of Europe. In Spain and many Orthodox Christian countries, gifts are not exchanged until this date - with the idea being that the gift giving on this day recalls the gifts given to the baby Jesus by the magi upon their arrival in Bethlehem.

Kronos was the equivalent of Saturn in Greek culture.

It is worth noting that these accounts were of course written down post-Christianisation so it may be that the writer had a vested interest here in making the pre-Christian festivals seem particularly savage and bloody.

There is some suggestion that mistletoe was part of the fertility rites that also took place around this time, with a pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon festival of Mōdraniht seemingly focused on female spirits coinciding with early Christian celebrations of Christmas Eve. Mistletoe also featured strongly in Old Norse myth, where the whiteness of the berries was interpreted as a symbol of male fertility,

Prominent folklorists like James Frazer and Mikhail Bakhtin argued that role reversals like the Lord of Misrule drew from specific Saturnalia traditions. A similar custom practised in the Roman period saw a man dressed as Saturn elected as a ‘king’ for the duration of the festival. Other are less convinced of the case for a direct influence from one to the other, but the similarity is interesting nonetheless.

Saint Francis of Assisi was one hell of a guy. Known for his dedication to a simple life of poverty and his very un-medieval kindness towards animals, St. Francis did some truly mad stuff in his time. During the fifth crusade to Egypt (1217-1221), Francis literally walked into a crusader camp outside the city of Damietta and decided to have a go at converting the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt, al-Kamil. Whether the Sultan was genuinely impressed by Francis’ efforts, or was just amused at his boldness, he heard him out and let him wander back unharmed to the Christian camp.

You might be thinking “December is not mild, babe” but during the early medieval years c. 950-1300, it actually was! We’re not sure exactly why, but climate science points towards a prolonged period of warm-ish weather patterns during the Middle Ages which is known as the Medieval Warm Period. The colder months were yet to come in January, February and even March.