On Monday, over on my Instagram, our weekly quiz theme was ‘Unfortunate Royal Deaths’. Voted for by followers, we had a great time together guessing the fates of some unlucky medieval royals whose lives ended in gruesome, unexpected, or, frankly, absurd ways. So much fun, in fact, that the participators wanted me to bring together some of those wacky stories in the more permanent form of a Substack post. Thank you so much to all of you who played along and, if you don’t already follow me and fancy joining in with the quiz each weekend, you can do so by clicking HERE.

It’s fair to say that the Middle Ages were pretty brutal. In a world without modern surgical practices, antiseptic, and pathogen-free drinking water, and that was regularly torn apart by rebellion, pandemics, wars and disaster, living to a ripe old age and dying peacefully in bed was a good deal rarer than it is in the 21st century. Though we generally assume that monarchs, warlords and aristocrats might have had an easier time of things than the average Joe, living the life of the 1% and being caught up in medieval politics brought its own bucketload of complications. Whether it was overindulging on the richer foods at court or simply picking a fight on the battlefield with the wrong guys, it was easy for a medieval monarch to end up spectacularly dead.

Here are ten medieval leaders whose unfortunate deaths will surprise, amuse and amaze…

Attila the Hun (c. 406 - c. 453)

Attila the Hun was a semi-nomadic warlord riding at the head of an enormous army of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans and Bulgars with which he terrorised the ailing Roman Empire. Known for his devastating raids on the settled cities of the Roman lands and the skill of his mounted warriors, Attila was despised and feared all over Europe. Though we have few accounts of Attila’s appearance, 6th century historian Jordanes, citing an earlier source written by the Greek-speaking historian Priscus, paints a portrait of a terrifying but adept ruler:

“He was a man born into the world to shake the nations, the scourge of all lands, who in some way terrified all mankind by the dreadful rumours noised abroad concerning him. He was haughty in his walk, rolling his eyes hither and thither, so that the power of his proud spirit appeared in the movement of his body. He was indeed a lover of war, yet restrained in action, mighty in counsel, gracious to suppliants and lenient to those who were once received into his protection. Short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his eyes were small, his beard thin and sprinkled with grey; and he had a flat nose and swarthy skin, showing evidence of his origin.” 1

As a society of pastoral horsemen, the Huns were an oral culture who didn’t record their own history using writing, meaning that historical sources for Attila’s life (like this one) were almost exclusively written by people who had been his enemies. The complications of this in terms of believing what you read are obvious, however, Priscus of Panium, whom Jordanes cites for his sketch of Attila, was at least around during Attila’s lifetime. In fact, he was a witness to and a participant in Attila’s life story, having personally served in the diplomatic embassy of Roman Emperor Theodosius II at the Hunnic court in 449 AD.

It is from Priscus that we get the most widely accepted version of how the fearsome Attila died. According to Priscus’ account, Attila died suddenly at a feast celebrating the most recent of his many, many marriages. Having taken part in the revelry, gotten very drunk and having had an all-round lovely time, reportedly Attila suffered a catastrophic nosebleed and died. Historians have theorised since that he may have suffered devastating internal bleeding, possibly due to ruptured oesophageal varices, a condition that can develop through years of heavy alcohol consumption. Attila’s years of raiding and boozing finally caught up with him, with the great Hunnic conqueror’s career ended in an instant with a haemorrhaging schnoz.

Shocker rating: 4/5

An underwhelming final scene for a tremendously big character.

King Henry I of England (c. 1068 - 1135)

King Henry I of England, the son of William the Conqueror, was an interesting character. Ever impulsive and immune to good advice, in his youth he and his brother William dumped a chamber pot full of piss over their elder brother Robert’s head and accidentally started an actual war. Later on in life, after the tragic death of his son in an English channel shipwreck, Henry found himself without any legitimate heirs, spending too much time making illegitimate ones with too many mistresses instead of hanging out with his wife.

Ultimately, Henry’s death was down to a similar lack of self-restraint. Henry’s favourite food was lampreys, a wriggly eel-like fish. Against the express advice of his doctor, Henry got carried away at dinner and gorged himself on lamprey pies. Shortly after, he began to feel unwell and within a week, his stomach complaint had gotten so serious that he died. The takeaways, I suppose, are that moderation is key and that you should always take your doctor’s advice.

Shocker rating: 2/5

If Henry had just done what he was told for ONCE…

Prince Philip of France (1116 - 1131)

Prince Philip of France was briefly the co-ruler of France with his Dad, King Louis VI from 1129 to 1131. He was daddy’s favourite but to everyone else was better known for being belligerent and disobedient. A near-contemporary writer, Walter Map, writing in the decades just after Philip’s lifetime, stated that he "strayed from the paths of conduct travelled by his father and, by his overweening pride and tyrannical arrogance, made himself a burden to all."2 Ouch.

In what could be described as a freak medieval road traffic collision, Philip was killed while out riding with his boys by the River Seine in Paris. As they were happily cantering along, a large black pig darted across the road in front of them out from a nearby dungheap on the quay. Philip’s warhorse tripped over this unexpected obstacle, catapulting Philip to the ground. Chronicler Orderic Vitalis tells us that the fall “so dreadfully fractured his limbs that he died on the day following”.3

Philip’s death had quite the impact on the French royal family. During his lifetime he had expressed a desire to travel to the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem. As this ambition never materialised, Philip’s pious younger brother, the future King Louis VII, took the cross as king of France in 1147 and travelled to the Holy Land on the Second Crusade in part to fulfil the vow of his deceased brother. The whole thing was a complete disaster and may have contributed in no small part to Louis’s acrimonious breakup with his wife, the formidable Eleanor of Aquitaine. Basically, that stray pig and Philip’s untimely death have a lot to answer for.

Shocker rating 4/5

Death by bolting pig ranks high on the medieval misfortune scale…

George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1449 - 1478)

George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, was the brother of King Edward IV and the future King Richard III. He was a big player in the Wars of the Roses which had made his brother king in the first place, but was constantly switching sides in pursuit of his own interests.

George had initially supported Edward’s claim to the throne but changed his mind when Edward fell out spectacularly with George’s father-in-law, the Earl of Warwick. Warwick, who had earned the nickname ‘kingmaker’ due to the power and influence of his armies in the wars, deserted Edward VI (taking George with him) to ally with Margaret of Anjou, the queen of the deposed former king, Henry VI. Ultimately, George bet on the wrong horse. Warwick’s efforts to restore Henry VI to the throne of England failed and Warwick was killed in battle with Edward’s forces at the Battle of Barnet in 1471. After a bit of grovelling, Edward chose to forgive George for this betrayal and make him the Great Chamberlain of England as a peace offering.

All was well until 1477 when once again George found himself in hot water. Upon the execution of two of his men who had been put to death for plotting against Edward, instead of keeping quiet, George sent a pal to burst into parliament and defend the dead men in front of the entire royal court, raising suspicions that the Duke of Clarence might indeed have had one eye on his brother’s crown.

Eventually, by 1478, Edward lost his patience with his wayward younger sibling and ordered George’s execution. Allegedly, as George was a known alcoholic, he was executed by being drowned in a massive vat of Malmsey Wine - his favourite tipple. There is some doubt as to whether this actually happened. Even if it did, there is disagreement in the sources about whether this method of execution was chosen by Edward personally as a big fat ‘**** you’ to his treasonous brother or whether George, in a final act of childish teasing, requested this unusual death on his own terms.

Shocker rating: 3/5

Inventive, but the consensus is that there are worse ways to go…

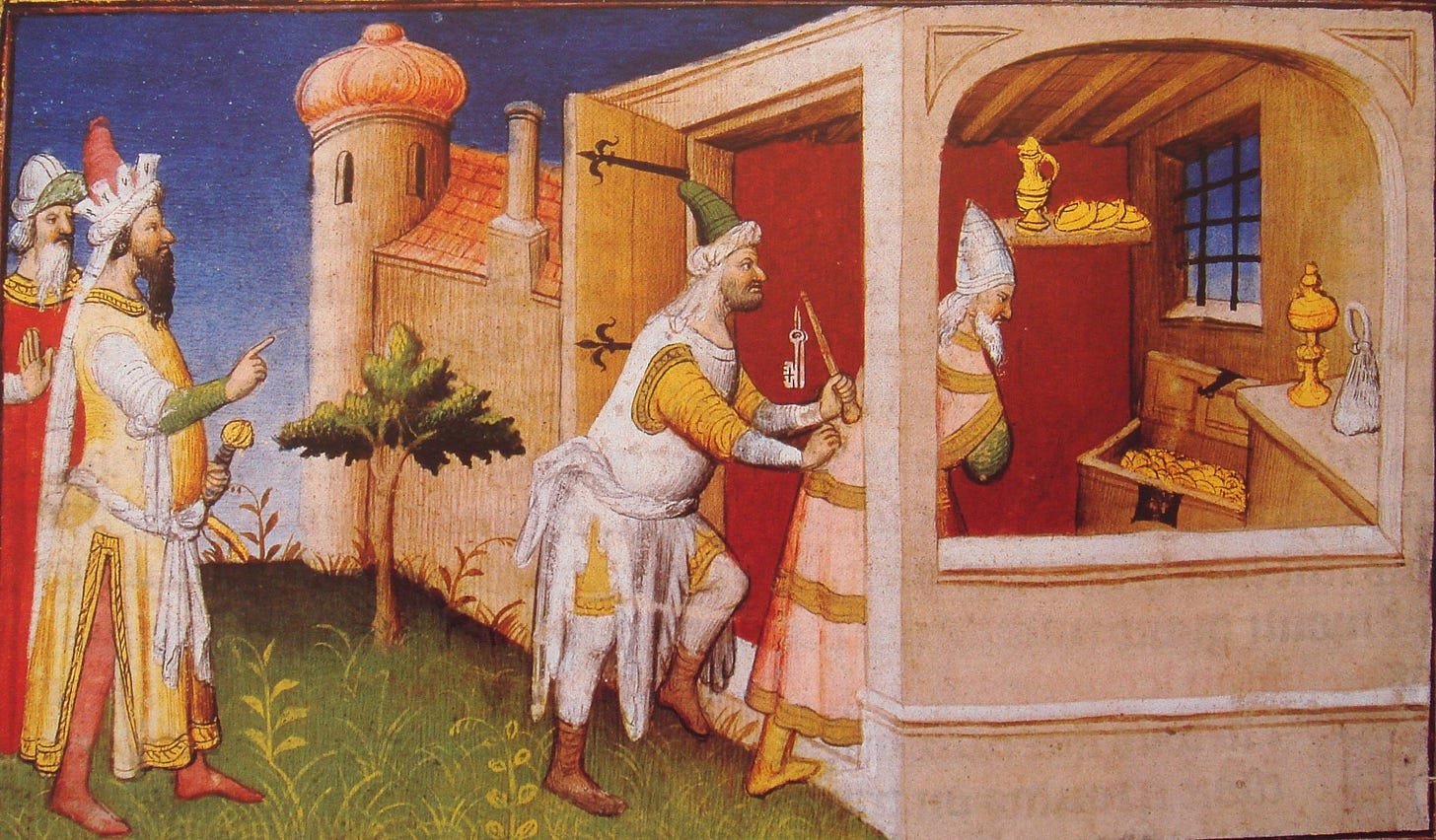

Caliph Al-Musta’sim of Baghdad (1213 - 1258)

If there were a golden rule in the 1200s, it probably should have been ‘do everything you can to not end up in a fight with the Mongols’. The routine was simple: the Mongols would get the ball rolling by sending their ambassadors with a message containing something along the lines of ‘let us take over your lands or else’. At this point you had two choices: cut your losses and ally with the new Mongolian overlords, or buckle up for the fight of your life, knowing from recent history that putting up resistance and losing made it likely that entire cities would be slaughtered as a warning to the next guys planning on making it hard for them.

The Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta’sim of Baghdad, on the advice of his viziers, chose to resist. Badly. Upon receipt of the demands made by Möngke, Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, the caliph sent the emissaries packing and, crucially, failed to bolster the defences of Baghdad in preparation for the now inevitable Mongol storm.

By February of 1258, the Mongol armies, led by Möngke’s exceptionally gifted brother, Hulegu, had sacked the city of Baghdad and Al-Musta’sim was captured alive. According to ancient Mongol tradition, the caliph needed to be executed without shedding any blood. For all their brutality, the Mongols believed that to shed royal blood was to bring bad luck.

What’s the loophole? Well, as long as that royal blood isn’t visibly spilled onto the earth, things should be alright. The Mongols promptly rolled the caliph up in a Persian carpet and had him trampled over by Mongol horses. Grisly.

Shocker rating: 4/5

Leave it to the Mongols to adopt the Bear Gryll’s ‘Improvise, Adapt, Overcome’ mentality when it comes to circumnavigating politically inconvenient traditions.

Sigurd Eysteinsson (Ruled c. 875–892)

Sigurd Eysteinsson, or Sigurd the Mighty to his friends, was a viking Earl of Orkney. According to the Norse sagas, after the Battle of Hafrsfjord and the unification of Norway c. 872, the Orkney and Shetland islands in the far north of Britain became an outpost of sorts for troublesome exiled vikings who would raid their former homelands in Scandinavia. Sigurd’s elder brother, Rognvald, helped King Harald Fairhair of Norway keep this rabble under control and he eventually bequeathed his title of Earl to Sigurd.

The Orkneyinga Saga, that charts the history of the Earls of Orkney, claims that at the height of his power Sigurd challenged a native enemy, Máel Brigte the Tusk (so named for his prominent teeth), to a pitched battle of forty men vs. forty men. In an extremely rogue move, Sigurd cheated and brought eighty men, easily winning the battle and killing Mael. He strapped Mael’s severed head to his horse and headed for home.

Well, karma is a bitch. Because according to the stories, while riding home, Sigurd caught his leg on one of Mael’s famous buckteeth and cut himself. Within days the wound was inflamed and infected, oozing pus and blood all over the place until finally Sigurd perished in agony. Either as a result of sepsis or gangrene, Sigurd the Mighty was effectively killed by the dead man he had cheated.

Shocker rating: 5/5

In the immortal words of Taylor Swift, Karma is a God.

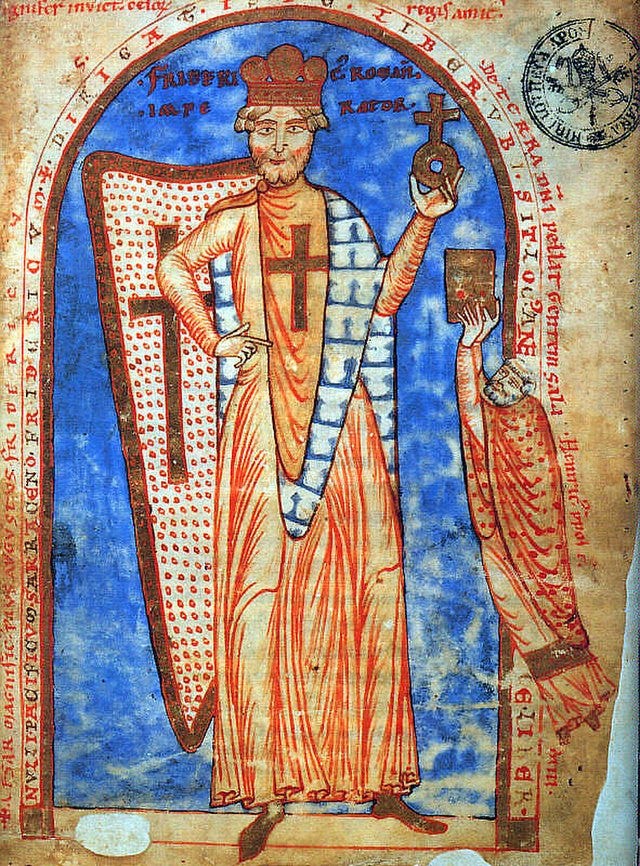

Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122 - 1190)

Frederick Barbarossa was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. The position was an elected one, usually held by a Germanic duke, and Frederick had enjoyed a meteoric rise to prominence - battering rivals left, right and centre. He had gained a serious reputation for skill in battle and savvy political bargaining. Like many European leaders of this time, Barbarossa felt a keen desire to join in the Crusade campaigns to take the Holy Land away from the Muslims and ‘return’ Jerusalem to Christian hands.

As a young man, Barbarossa had accompanied his uncle, King Conrad III, on the Second Crusade which had taken him through Greece, Anatolia and Syria before returning home when the Crusade ended in failure. In his later years, he once again answered the call to the East and signed up to fight in the Third Crusade (sometimes called the ‘Kings’ Crusade) with King Richard the Lionheart of England and King Philip II of France.

It was on the arduous overland journey to the Holy Land that things went wrong for the aging warrior-king. There are conflicting stories about exactly what happened but reportedly the mighty Barbarossa was accidentally drowned in the River Saleph in modern-day Turkey. One anonymous account of the era claims that “against everyone's advice, the emperor chose to swim across the river and was swept away by the current”.4 Others suggest that he either paddled in to cool down and the weight of his armour dragged him under, that he was crossing the river fully armoured when his horse threw him off, or that he simply passed out from the heat while swimming.

With the death of the Emperor, the German troops turned around and went home.

Shocker rating 2/5

A damp squib end to an extraordinary life…

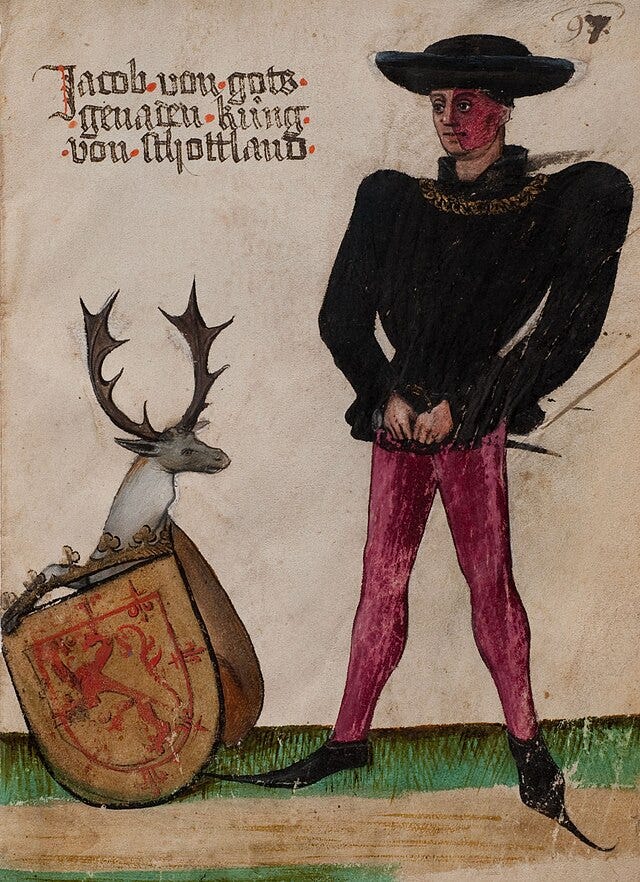

King James II of Scotland (1430 - 1460)

King James II of Scotland ruled from 1437-1460 and had a particularly dramatic life. As the eldest surviving son of King James I of Scotland, he became king as a six year old child, following the assassination of his father. His father (obviously) had been unpopular and much of poor James’ reign was characterised by violent power struggles with Scottish nobles who thought their own family was a better shout for the throne.

In 1460, as part of an effort to increase Scotland’s standing in the eyes of the English, the young King besieged the English-held castle at Roxburgh on the River Tweed. Like many young men, James got excited about new technology - particularly new military tech. He had imported a fancy new cannon from Flanders for the occasion and was keen to demonstrate that power to the English who had been bullying Scotland for centuries by this point. Unfortunately, when the aforementioned cannon was fired, James had been standing too close to it and he was fatally injured. A piece of debris from the gun reportedly snapped his thigh bones clean in two meaning he probably died of catastrophic internal bleeding.

Shocker rating: 3/5

Please be careful with explosives.

King Bela I of Hungary (c. 1015 - 1063)

Bela’s life was pretty eventful. He spent many years in exile in Poland as a child after the execution of his father Vazul and later took the throne of Hungary by force after rebelling against his older brother Andrew. As king, Bela successfully defended Hungarian independence against the growing might of the Holy Roman Empire and, by putting down pagan rebellions, solidified Hungary’s status as a Christian kingdom.

In September 1063, during an audience in the summer palace at Dömös, Bela was due to address his nobles on the important question of succession under renewed threat of German invasion. As Bela moved to sit down on his throne, the heavy wooden frame above Bela’s throne collapsed and crushed him underneath it - much to the horror of the assembled court nobles. A Hungarian source describes how when Bela was dug out from underneath the debris, he was “half-dead”5 and was whisked away to Kanizsva Creek in the west of Hungary where he died on 11 September 1063.

Shocker rating: 1/5

Unfortunate, but at least he died at home amongst friends…?

King John (Jan) of Bohemia (1296 - 1346)

King John of Bohemia was a renowned European battlefield superstar and had fought Hungarians, Russians, Austrians, Englishmen and whoever else he fancied. Born in Luxembourg but educated in Paris, Jan was very sympathetic to the French and took their side in the Hundred Years War against the English.

At the pivotal Battle of Crécy in 1346, everything went drastically wrong for the French very quickly. John had been put in charge of the French vanguard alongside the Counts of Alençon and Flanders and chose the wrong moment to plunge deep into the English ranks only to be surrounded and slaughtered. Some would argue that putting John in charge of such an important part of the army that day was a rogue choice. It is true that he had a proven track record of battlefield success, but on the other hand… he was blind.

While crusading in Lithuania around ten years prior to the Battle of Crécy, John began to lose his eyesight (probably due to a condition called ophthalmia). Nevertheless, on the day of the battle, he was determined to take part.

French chronicler Jean Froissart described what happened as follows:

“...for all that he was nigh blind, when he understood the order of the battle, he said to them about him: 'Where is the lord Charles my son?' His men said: 'Sir, we cannot tell; we think he be fighting.' Then he said: 'Sirs, ye are my men, my companions and friends in this journey: I require you bring me so far forward, that I may strike one stroke with my sword.' They said they would do his commandment, and to the intent that they should not lose him in the press, they tied all their reins of their bridles each to other and set the king before to accomplish his desire, and so they went on their enemies. […] [the king] fought valiantly and so did his company; and they adventured themselves so forward, that they were there all slain, and the next day they were found in the place about the king, and all their horses tied each to other.”6

According to another account, the Latin Cronica ecclesiae Pragensis Benesii Krabice de Weitmile, when the knights at his side told John that the battle was lost and that he ought to save his own skin and bounce, he replied “far be it that the King of Bohemia should run away. Instead, take me to the place where the noise of the battle is the loudest. The Lord will be with us. Nothing to fear. Just take good care of my son.”7

Shocker rating 5/5

Commander blindness feels like an issue someone should have flagged up earlier…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, I have a small favour to ask of you! Please hit the ‘like’ button and leave a comment below on which facts surprised you the most. If you know someone who might find this article interesting - share away! And please subscribe for free with your email so that you never miss a new post. Your likes, comments, subscriptions and shares all help the blog get seen by more eyes which in turn gives me the space, resources and reach to create bigger and better content for you all.

Further Reading

These below links are affiliate links. If you choose to purchase a product using the links provided here, I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. By using these links you are supporting me and my work, allowing me to continue to get creative and keep posting fresh content for you all. For this, I cannot thank you enough!

Attila the Hun: Attila the Hun by John Man is a great start if you’re interested in the Hunnic empire and their role in the Fall of Rome. John Man is an excellent storyteller and his biographies are all brilliant!

King Henry I: England Under The Norman And Angevin Kings, 1075-1225 by Robert Bartlett is a comprehensive account of this period. This one is a deep dive.

George, Duke of Clarence: The Wars of the Roses, England’s First Civil War by Trevor Royle is a great and accessible account of this period.

Caliph Al Musta’sim: The Mongol Storm by Nicholas Morton. This is great for understanding the impact of the Mongol invasions in the Middle East.

Sigurd the Mighty: Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. This is the saga that gives us the story of Sigurd, alongside the history of the other Viking ‘Jarls’ or Earls of Orkney.

Frederick Barbarossa: If you’re interested in learning more about the Holy Roman Empire and Barbarossa’s role within it, you can’t do better than Peter Wilson’s book, The Holy Roman Empire, A Thousand Years of Europe’s History. For Barbarossa specifically, John Freed’s biography is fantastic.

King John of Bohemia: Michael Livingston’s account of the Battle of Crécy is a corker. Crécy: Battle of Five Kings.

Jordanes. The Origin and Deeds of the Goths. Translated by Charles Christopher Mierow. Princeton: Princeton University. (1908) Accessible via Project Gutenberg https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14809

Walter Map. De Nugis Curialium

Ordericus Vitalis. The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy

Anonymous chronicle quoted in John Freed. Frederick Barbarossa: The Prince and the Myth. New Haven: Yale University Press. (2016).

The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum. Edited by Dezső Dercsényi. Corvina: Taplinger Publishing. (1970)

The Chronicles of Froissart. Translated by Lord Berners, edited by G.C. Macaulay. Harvard Classics. Available online at https://www.bartleby.com/lit-hub/hc/the-chronicles-of-froissart/the-campaign-of-crecy-10/

Chronicon Ecclesiae Pragensis Scriptores rerum Bohemicarum. Archived 4 March 2016 accessible on the Wayback Machine

Very interesting read! Perilous times! Looking forward to learning more!