Parchment, Pen Cutters and Poisonous Paints: Making a Medieval Book

Being literate in the Middle Ages was so #NotVegan...

It is both widely celebrated and lamented that there are few things easier in the 21st century than broadcasting your innermost thoughts to an audience. Whether we choose to exchange ideas by listening to podcasts on the treadmill, engaging in spicy political spats on Twitter (X now…?), or by picking up paperbacks in WHSmiths’ cheeky Buy-One-Get-One-Free deal, it can be hard nowadays to appreciate the labour that went into such communication during the Middle Ages.

Making books and sharing ideas in an age before the printing press, mass produced writing materials, and widespread use of paper was an expensive, specialist and time-consuming endeavour. Text had to be meticulously reproduced by highly-trained scribes copying entire books word-for-word and each copy of the same text might have its own unique ‘illuminations’, or decorations, produced by professional artists that reflected the owner’s personal tastes.

The specificity of the materials and skills involved in this arduous process meant that books were considered a symbol of status in a way that doesn’t quite translate to the modern era. When people who have read War and Peace make sure that it is *VERY VISIBLE* to visitors on their bookshelf, it reflects a modern judgement that the value of a book is largely determined by the perceived prestige of its content. A medieval courtier might similarly display a chunky Latin philosophical volume in their home to demonstrate how terribly intellectual they are, but people in the Middle Ages would have been more inclined than modern readers to focus on the materials used in the book itself as a reflection of the owner’s religious or cultural devotion, their family’s social standing, and their all-important wealth.

In other words, precisely due to the faff involved in its production, a finely decorated medieval manuscript was important as a luxury object, regardless of the things it might have contained - the designer handbag of its age if you will.

What was so difficult, then, about making a book in the Middle Ages? What were they made from? How can we interpret clues a manuscript gives us to draw conclusions about how and why they were made? By zooming in on a few things that make medieval books different from the ones we know and love today, we can shed some light on these questions.

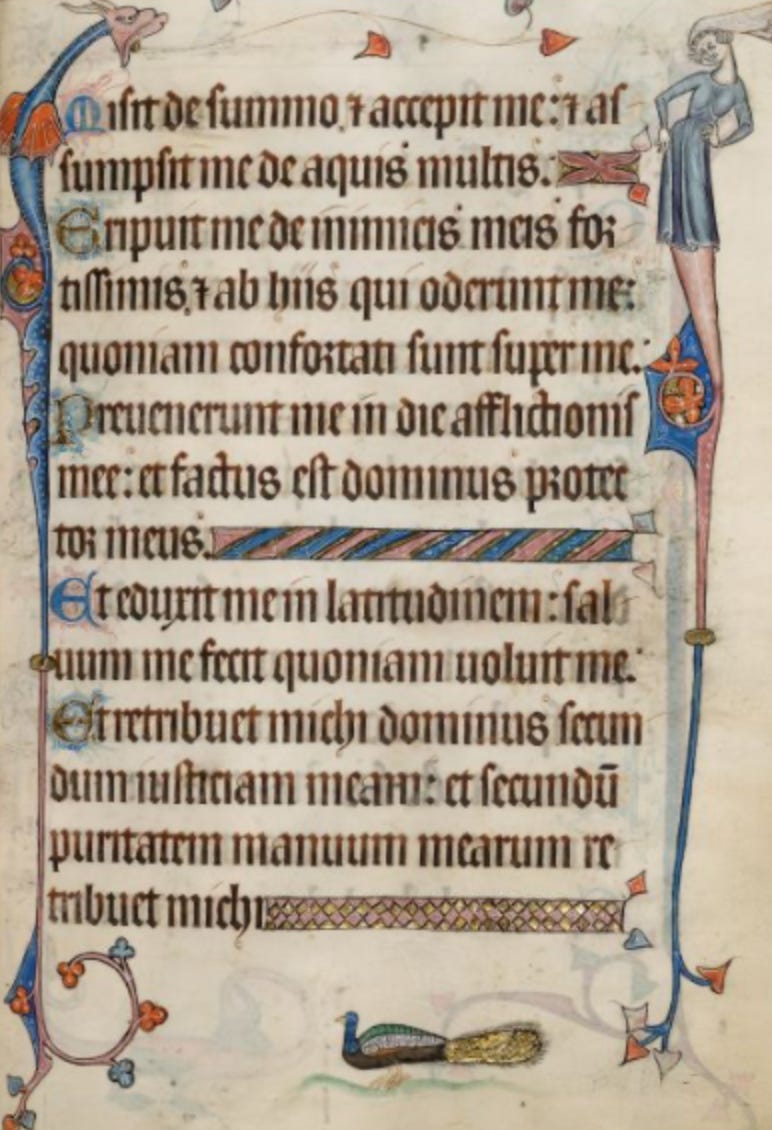

Above: Manuscript page containing the opening of The Book of Nehemias, from a French Bible c. 1280-1300, gold and ink on parchment. In the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MS 1998.538.1.

Making parchment was pretty grimy…

If you’re going to write a book by hand, the first thing you need is something to write on. Though paper was invented in China around the 2nd century CE and was relatively widely used in the Islamic world after the 750s, it took a long old time to arrive in Europe. While there is early evidence of paper being used sparingly in parts of Europe like Spain and Sicily, where there had been prolonged contact between Islamic empires and western Christendom, the most common writing material for medieval Europe was parchment.

Parchment was a durable writing material made from treated animal skins. A parchment maker would begin with the skin of a slaughtered goat, sheep or calf and would soak it in lime for weeks to cause the hair follicles to loosen. Using a curved board and blade, the skin would then be scraped clean of hairs and any remaining flesh, smoothing out the surface ready for the next step. Once cleaned, the skins were attached to a wooden frame called a ‘hearse’ with pins called ‘pippins’ and gently stretched into larger sheets, which caused oxidising chemicals in the skins to gradually shift the parchment in colour from translucent to white.

Above: Parchment was such an expensive material that even flawed parchment was often used despite obvious imperfections. Rather than turn a blind eye to holes, tears, and marks, some scribes and artists made these things into a decorative feature to avoid wasting an expensive sheet of material. This example of a beautified parchment hole is from the Tollemache Orosius, England (possibly Winchester), late 9th or early 10th century.

Find the book and flick through the pages for yourself here: British Library Add MS 47967, folio 62v. https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_47967_fs001r

After being scraped smooth one more time with a crescent-shaped blade called a ‘lunellum’ (derived from the Latin word for ‘moon’), and having the excess grease extracted from the surface using pumice stone or cuttlefish, the parchment was cut into sheets and ready to go.

This expensive, weeks-long process involved some grotty substances, some serious effort, and a great many pungent smells.

Did you know? Though parchment is a pretty robust material, it can be very reactive to heat and humidity. As pages of parchment respond to changing environmental conditions, they can become springy and start to buckle. To help keep the parchment nice and flat, books in the medieval period were stored horizontally, laying on their covers rather than stood upright, using the weight of the bindings to squash the pages down.

A medieval scribe had to be pretty patient

Being able to write in the medieval period was a sought-after skill that required specialist training. Many earlier scribes would have been writing day-in, day-out in monastic scriptoria - writing workshops based at a monastery where teams of monks trained as scribes would produce copies of books in between their daily prayers. Later in the Middle Ages, when an explosion in legal and documentary record-making caused a huge upsurge in the need for writing, more professional scribes emerged who did not operate as part of a monastic order.

Armed with a feather quill for a pen, writing some of the Middle Ages’ more ornate scripts was a painstaking job. A quill, made from the flight feathers of a large bird fashioned into a nib, would need to be re-cut into shape after almost every paragraph. Though scribes would normally cut their own quills, specialist pen-cutters did also exist. A skilled quill-maker would be able to produce approximately a ‘long-thousand’ (1200) quills in a single day.

Above: The Luttrell Psalter in London. This beautiful psalter is a perfect example of how a book might be used to express the wealth of a prestigious local family. This book was made in Lincolnshire on the orders of Sir Geoffrey Luttrell (b. 1276; d. 1345) of Irnham and the formal Gothic script used, as well as the detailed decorations throughout the book scream, ‘I was very expensive to make’. Indeed, just in case anyone might doubt who put up the money for the project, Sir Geoffrey had the following inscription added to it: 'Dns. Galfridus Louterell me fieri fecit’, or ‘Lord Geoffrey Luttrell had me made’.

Find the book and flick through the pages for yourself here: The British Library Add MS 42130, folio 35r. https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_42130_fs001ar

As writing trends developed throughout the Middle Ages, various different styles of handwriting or ‘scripts’ became fashionable at different times. The 12th - 15th centuries saw the prevailing popularity in high-status books of extremely formal ‘Gothic’ scripts which were characterised by thick, stylised lines and highly compressed letter forms. With multiple strokes of the quill often needed for each letter, producing work of this kind was extremely slow. A trained scribe writing in the most prestigious Gothic scripts could be expected to complete as little as between 150 to 200 lines per day. Scripts that were slow to write meant that the patron financing the production of the book would have to put up more money for the scribe’s time, which in turn meant that the use of scripts like these became a symbol of wealth and status in themselves.

Did you know? The word ‘manuscript’ comes from a combination of the Latin words for ‘hand’ (‘manus’) and ‘written’ (‘scriptus’). This term can be used to describe a whole range of medieval sources produced by hand: not just books but royal charters, court records, accounts, and personal letters too!

The Cardinal Rule: Don’t Lick your Paintbrushes

Unquestionably, one thing that makes some medieval books so infinitely appealing to us is their colourful illustrations and decorations. However, jazzing up a manuscript in the 1300s wasn’t as simple as popping down to Hobbycraft for some gouache. The paints used to create these images were often made with exotic pigments that may have travelled hundreds or thousands of miles before finally reaching the hand of the artist.

Most pigments were ground into fine powders before being mixed with adhesives to create a smooth paint, and this job in itself was both specialist and dangerous. Over-grinding certain pigments could cause them to lose their colour, and breathing them in over an extended period of time could quite literally kill you. Several of the most common pigments used to create base colours like white, green and red were highly toxic. ‘Flake white’ was made from lead carbonate, while the chemical name for ‘Vermillion’ is mercury sulphide. Similarly, ‘Verdigris’, which was used to mix a whole spectrum of greenish hues, was made from poisonous copper salts.

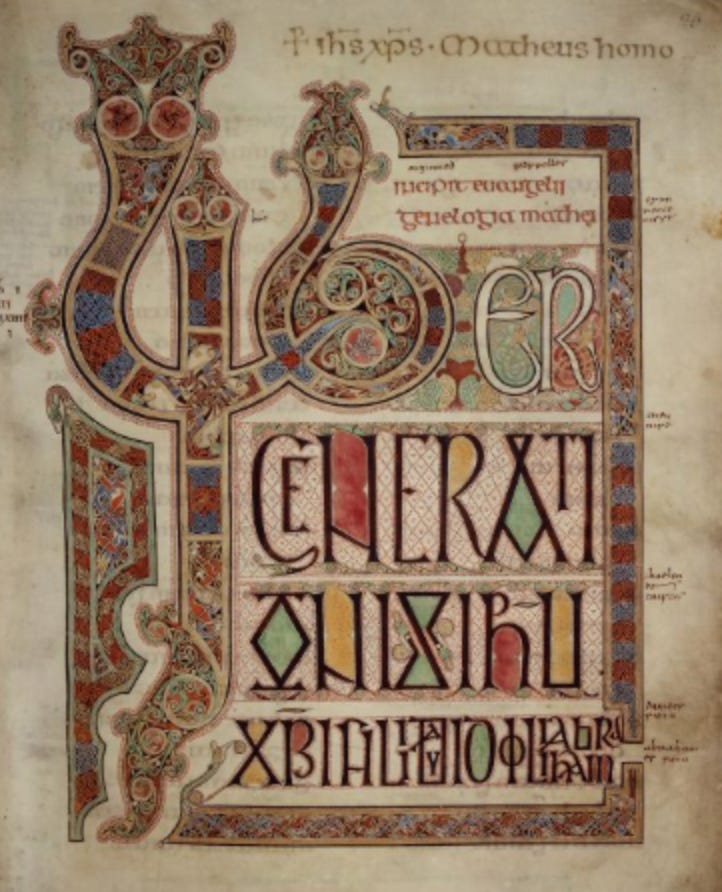

Above: The Lindisfarne Gospels, often celebrated as England’s finest medieval manuscript, used around 8 pigments to produce a spectrum of circa 94 different colours. Pigments were infinitely mixable and customisable.

Find the book and flick through the pages for yourself here: The British Library Cotton MS Nero D IV, folio 27r. https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=cotton_ms_nero_d_iv_fs001r

With the hassle and expense of pigments in mind, European manuscripts produced on a tighter budget might restrict themselves to flourishes of red or blue ink and forgo any illustration at all, while more elaborate manuscripts designed to emphasise the wealth and reputation of a family or institution might deliberately incorporate pigments that had to be obtained from Africa, Asia or the Middle East.

Did you know? Some pigments were worth their weight in gold, literally. Ultramarine was a deep blue colour that was extremely expensive and imported from Afghanistan, mined from specific caves in the mountains at the end of precipitous tracks. The extreme expense of the pigment meant that it was often reserved for highly symbolic religious purposes: to paint the heavens, or the clothes of the Virgin Mary.

All that glitters… is gold. It’s actually gold.

If paying to have your family manuscript smothered in luxurious imported pigments wasn’t quite ostentatious enough for you, there was still one more way to up the ante and show up all your pals at court with your new prayer book. Gold!

The most high-status medieval manuscripts are not shy when it comes to the use of bling and these objects, though hundreds of years old, often sparkle just as well now as they ever did. There were several methods for working gold into the production of a manuscript but the most common were gold-leafing and the use of gold as a kind of paint.

Above: The Codex Aureus, or ‘Golden Book’ in Stockholm. Produced in Canterbury around the mid 8th century, this blingy book positively shimmers with gold leaf. Mostly laid using the gesso method, the gold in this book is three-dimensional for extra *sparkle*.

Find the book and flick through the pages for yourself here: Royal Library Stockholm MS A 135, folio 10v. https://www.manuscripta.se/ms/100501

Gold leaf would have been applied over a thick and three-dimensional adhesive called ‘gesso’ which is a carefully balanced mixture of slaked plaster of Paris, lead carbonate, a natural adhesive (usually fish glue) and a sugar (usually honey). The gesso would be laid on the parchment with a quill and then gently breathed upon. The heat and moisture in the breath would activate the adhesive, allowing the artist to then lay on and burnish the gold leaf. Gesso, being slightly raised from the surface of the parchment, helped the gold leaf to catch the light and add an extra dimension to the shine.

In contrast to the gesso method, ‘shell’ gold is a way of working gold so that it can be applied 2D like a paint. Shell gold involved mixing real powdered gold with gum arabic, a resin, or similar natural adhesives. This method’s strange name originates in the medieval practice of using seashells as palettes to hold paints and pigments.

Did you know? There are a handful of professional scribes and illuminators who still use these traditional techniques. Click HERE to see a video of one such professional demonstrating laying gold with gesso.

Did any of these facts surprise you? If you enjoyed this post, please consider leaving a comment, liking the article, or, even better, subscribing to the blog and sharing it with your friends. All of the aforementioned kindnesses help me to carry on doing my PhD research and making free content for the medieval-curious. Thank you for visiting!

And Cromwell had them burned in great piles!

Fascinating!